Havana Cuba. — An open letter sent to the president of the ICRT and which was published in The Young Cuba It is the most recent episode in the long struggle of Delia (Lela) Sánchez Echevarría to vindicate the figure of her father, Aureliano Sánchez Arango, who was Minister of Education during the government of Carlos Prío Socarrás (1948-1952).

Lela Sánchez’s open letter was motivated by the defamatory treatment given to Aureliano Sánchez Arango on NTV by journalist Arlen García Rosales on August 16, in a report on the occasion of the 71st anniversary of the death of Eduardo Chibas.

In said report, the journalist echoed the argument repeated for decades by the official story against Sánchez Arango, accepting Chibás’s accusations against him as true, without having evidence and without granting the right to reply.

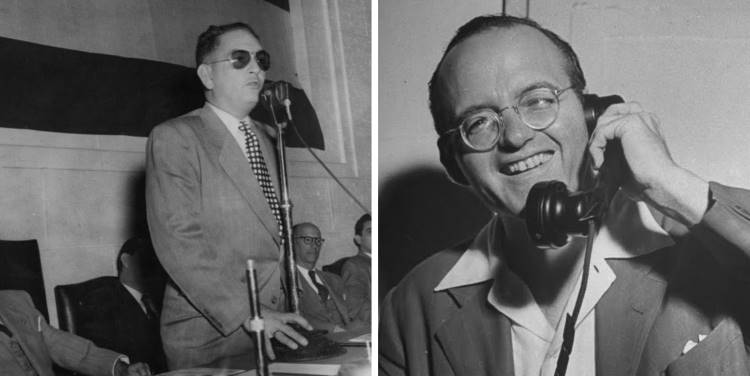

Chibás claimed that Minister Sánchez Arango had bought land in Guatemala with the millions he stole from money for school breakfast. But he never got to prove it. He never showed the evidence that he claimed to have and that Sánchez Arango ordered him to present.

The dispute between Chibás and Sánchez Arango, making mutual recriminations, lasted three months, from June to August 1951. Since Chibás had not finished showing the supporting documents against the minister that he said he kept in a suitcase, he was the object of skepticism and ridicule. Even the very popular comic actors Garrido and Piñeiro made jokes about Chibás’ “la maletona”.

Probably those teasing for the evidence that he had not finished showing influenced so that on the night of August 5, 1951, in his radio program “Al aire”, in a fit of hysteria, Chibás drew a revolver and shot himself in the abdomen. Seven decades later, the circumstances surrounding that dramatic event, known as “the last knock on Chibás,” are still unclear.

Some say that the evidence against Alemán was stolen from Chibás’ briefcase by individuals in the service of Sánchez Arango, but it is most likely that it did not exist.

There are those who affirm that Chibás did not really want to take his own life, but rather to impress. The wound, which was near the groin, did not necessarily have to be fatal. If he died it was due to an infection and other complications that arose. And there are those who affirm that the person responsible for the complications that caused Chibás’ death on August 16, after eleven days in the Havana Medical-Surgical Center, was Dr. Gustavo Aldereguía. According to these versions, his bosses from the Popular Socialist Party (PSP), still hoping to return to the government by allying with Fulgencio Batista and who did not swallow Chibás for his anti-communism, had ordered the doctor to prevent the Orthodox leader from leaving alive. of the hospital. The communists wanted to prevent Chibás from triumphing in the 1952 elections, as it seemed he would.

Lela Sánchez’s letter is not the first she has done to claim her father’s honor. She has written several claims to many official instances and even a book. They have never had an answer. But now that social networks and alternative media exist and Cubans dare to question the versions of the ruling party, the voice of this woman who demands that the truth be told is making itself felt. And it is very good that it happens. It is time for us Cubans to understand that the history of the Republic was not as Castroism has been interested and agreed to tell it: in black and white, in the style of San Nicolás del Peladero.

The writers of the official historiography have wanted to show that all the politicians of “the mediated republic” (as they like to call it), except Antonio Guiteras and Eduardo Chibás, were corrupt, demagogues, submissive to the US government, anti-democratic, anti-popular, and that Fidel Castro, with his revolution, freed us from his crimes and robberies.

The official bias is not surprising when he recounts the lawsuit between Eduardo Chibás and Aureliano Sánchez Arango, who is always denigrated. For the rancorous Castroists, the fact that Sánchez Arango was chosen to form part of a government in exile if the invasion of Brigade 2506 had succeeded in 1961 weighs more than the active role he played, at the head of the Triple A organization, in the fight against the Batista dictatorship.

Eduardo Chibás, in whose party Fidel Castro began his political adventures, has been idealized by Castro’s historiography. It is time, for the sake of truth, that we also get out of that myth and we can have a more objective view of his figure.

Chibás, when he was studying at the university, faced the Machado dictatorship. A faithful follower of Dr. Ramón Grau San Martín, he was one of the first to join, in 1934, his Cuban Revolutionary Party (Authentic). But in 1947 he created the Orthodox Party, a detachment from authenticity that, with the slogan “shame against money” and a broom as a symbol, promised to end administrative corruption and clean up Cuban politics.

In the 1948 elections, Chibás was defeated by the ruling party’s candidate, Carlos Prío, who had been his friend and comrade in the struggle since the days of the struggle against Machado.

The tenacious and charismatic Chibás, who was an accomplished speaker and debater, did not give up. As with Prío the evils of the Grau government became more acute, the Orthodox ranks soon grew. Chibás and his party generated so much sympathy that, despite his death, in the elections that should have been held in April 1952, the candidate with the most possibilities was the orthodox Roberto Agramonte. But those elections were never held because a month earlier, on March 10, 1952, Batista, whose candidacy had no chance of winning, staged a coup and overthrew President Prío.

Eduardo Chibás was a nationalist politician, as close to social democracy and corporatism as Grau. But he suffered from a sick messianism that led him to ensure that Cuba had reserved in history “a great destiny, but he must fulfill it.”

Chibás did a lot of damage to democratic institutions due to the irresponsible and incendiary way in which he launched accusations left and right against the governments of Grau and Prío, which were, despite all their defects, the most democratic that the Republic had.

The most probable thing is that Chibás, if he had reached the presidency, would turn out to be another populist ruler, demagogue and politician that abounds so much in Latin America. He would hardly have been able to eradicate corruption and gang activity, because he was as committed as Grau and Prío to his former revolutionary comrades from the warring factions who had become gunmen.

But no matter how the government of Chibás, or of Roberto Agramonte, his replacement, turned out, it would not have been able to reverse the course of constitutionality and democracy and everything that came after 1952 would have been avoided: the Batista dictatorship, the Fidelista insurgency and the establishment of a totalitarian regime that has lasted 63 years and has Cuba plunged into the worst crisis in its history.

OPINION ARTICLE

The opinions expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the issuer and do not necessarily represent the opinion of CubaNet.

Receive information from CubaNet on your cell phone through WhatsApp. Send us a message with the word “CUBA” on the phone +1 (786) 316-2072, You can also subscribe to our electronic newsletter by giving click here.