The surgeon Walter Zimmer had followed each step carefully through the Argentine open television, which he watched frequently since he had returned to Cologne with his family, at the end of the 1970s, to find the medical job that was denied him. in the capital.

He had seen the departure of President Roberto Viola and the inauguration of Leopoldo Galtieri in December 1981, the popular mobilizations in the streets of Buenos Aires and the repression instructed by the Military Junta that further deteriorated the social climate, already hit by the subjugation of the freedoms, the violation of human rights and the critical economic situation.

Zimmer, his wife and their daughters had been part of that audience that from seven o’clock also watched the news that betrayed war plans, provocative maneuvers and dissuasive actions, all of which evidenced a rapid escalation of tensions with the United Kingdom.

The 38-year-old doctor was convinced of the justice of the Argentine claim and, despite the dictatorships that coexisted on the banks of the River Plate, he made the decision. After the Military Junta activated Operation Rosario and the troops landed in Stanley to raise the Argentine flag, on April 2, 1982, after a century and a half of British occupation, Zimmer spoke with his wife and went to the Argentine consulate in Cologne.

***

180 kilometers away, in the Obelisco de Las Piedras neighborhood, Luis Rosadilla was building a bread oven with his father, while they talked about the inevitable news. Old Rosadilla’s mouth trembled with indignation and his 28-year-old son, who still had the thinness that eight years in prison had caused him in Libertad, looked at him with the same admiring eyes with which he discovered the trade confectioner in his first years of life.

In addition to that livelihood, Luis inherited from his father a love for Bella Vista and an anarchic aura. They were close friends and the two had suffered the separation in prison that followed the guerrilla activity of the young Tupamaro. But since February 1982 they had resumed the talks and now, in addition to the bitterness, they shared the indignation of the British imperial response to defend their colonial hindrance.

Then Rosadilla did not think about it and automatically, as if it were a natural reaction to a matter awarded in another century, he went to the Argentine embassy in Montevideo ready to channel his act of repudiation; to turn his irritation into a conduit for action in the service of the Argentine cause.

***

There, in the Prado, lived Enrique Martínez Larrechea, four years younger than Rosadilla. He was the son of a militant and nationalist leader active during the dictatorship, although his political resistance was concentrated in the university coordinators of the National Party, where the Wilsonian effervescence was grounded. Together with Jorge Gandini and Javier García, he had worked for the No in the constitutional plebiscite of 1980 and the following year’s march had been planned, to a large extent, in that home.

Like Zimmer and Pinkadilla, he had a spontaneous reaction. He walked down Juan Carlos Blanco street to Agraciada and entered the Casa Quinta Aurelio Berro, where the embassy was located, receiving the solidarity of men and women, young people and veterans.

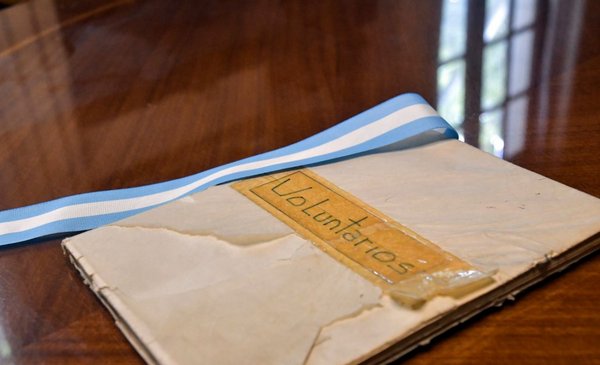

“I want to sign up as a volunteer for the defense of the Malvinas,” Martínez Larrechea told the man who wrote down his personal data in a small notebook that had the title “Volunteers” on the cover.

Notebook in which some of the Uruguayan volunteers were recorded

A total of 763 names appear on those sheets, handwritten in blue ink and on other lists that today form part of the historical-diplomatic archive of the Argentine embassy in Montevideo, including that of José Nino Gavazzo, who enlisted to fight and dispossess the British crown of the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The vast majority of these men and women were Uruguayans, although there are also Argentines, some Paraguayans, a Latvian and an Italian, among other nationalities.

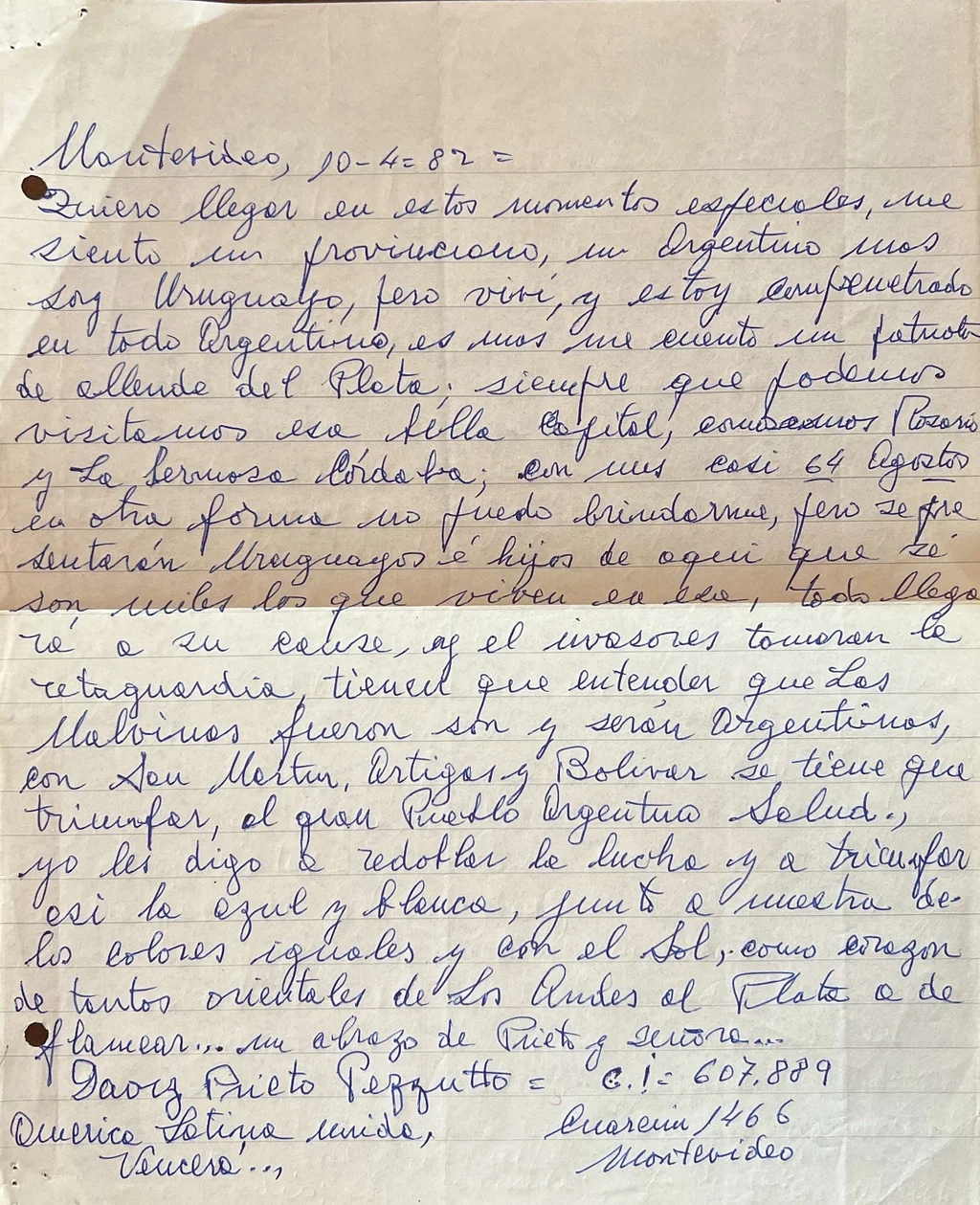

In the mansion located in Cuareim 1470, where the embassy operates today, letters of solidarity and encouragement from Uruguayans are also kept. Curiously, one of them, dated April 10, 1982, was sent from the same place where the embassy is today. Another was written in a medical prescription and a telegram sent from Paso Molino also survives.

Letter from a Uruguayan in solidarity with the Argentine cause sent from the same place where the embassy is located today

But the jewel that is exhibited in one of the rooms on the second floor is that notebook that shows that an entire family was enlisted behind the Malvinas issue. There are five Cabrera-Villalba listed: the father, the mother and their three children.

Forty years later, Martínez Larrechea still believed that there were only a handful of Uruguayan volunteers, but at the commemoration event organized by the Argentine embassy on Friday, April 1, Ambassador Alberto Iribarne surprised him with the news that the Uruguayan legion –accompanied by of some foreign residents – had been large enough to form a brigade.

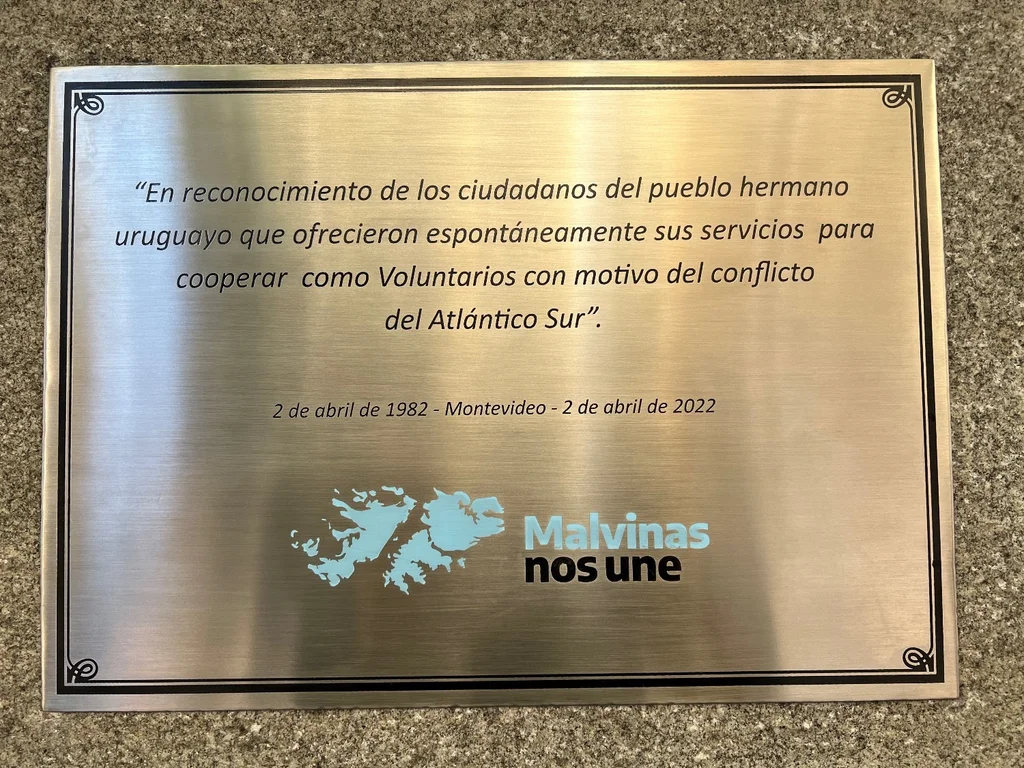

At the meeting in which there were other invited volunteers –including Hugo Manini Ríos, director of La Mañana and brother of the leader of Cabildo Abierto–, the ambassador said that this selfless act of cooperation constituted the greatest expression of solidarity of one people with another. , while unveiling a plaque of recognition for the Uruguayan citizens who spontaneously offered their services to cooperate as volunteers due to the conflict in the South Atlantic.

Plaque located on the facade of the Argentine embassy in Montevideo that recognizes the Uruguayan volunteers

That was the case of the 24-year-old white militant. His actions were motivated by a federal background and a nationalist sense. The defense of the islands was a historical mandate that transported him to Oribe’s actions against the Europeans, he explains now.

Martínez Larrechea had assumed the sacrifice. His action was serious and his commitment sincere. He was prepared to go if he was called from Buenos Aires, although fear assailed him when he left the embassy.

***

Zimmer told the consul to list him as a surgeon and combatant. And his diplomatic interlocutor warned him that if the war dragged on, reservists from all sides might be summoned.

Unlike Rosadilla, who could not withstand the weight of a school bag and did not pass a 50-meter test as a result of his precarious physical condition in prison, Zimmer was an athlete and knew how to shoot, although he had no military training or knew how to handle weapons of war.

He says that he did not sign up to appear, that it was not a youthful madness but a logical reaction, that he was convinced and that he was aware of the risks involved in his decision. Before going to the consulate he had discussed it with his wife and had taken care of arranging the legal part in case he didn’t come back. Every day he woke up wondering if they were going to call him. He lived those ten weeks with tension and uncertainty. He was expecting the summons, but the war ended early and as far as is known neither he nor the rest of the 762 were summoned to the front lines. Four decades later he reaffirms his decision with the same conviction of that time: he would not hesitate to do it again.

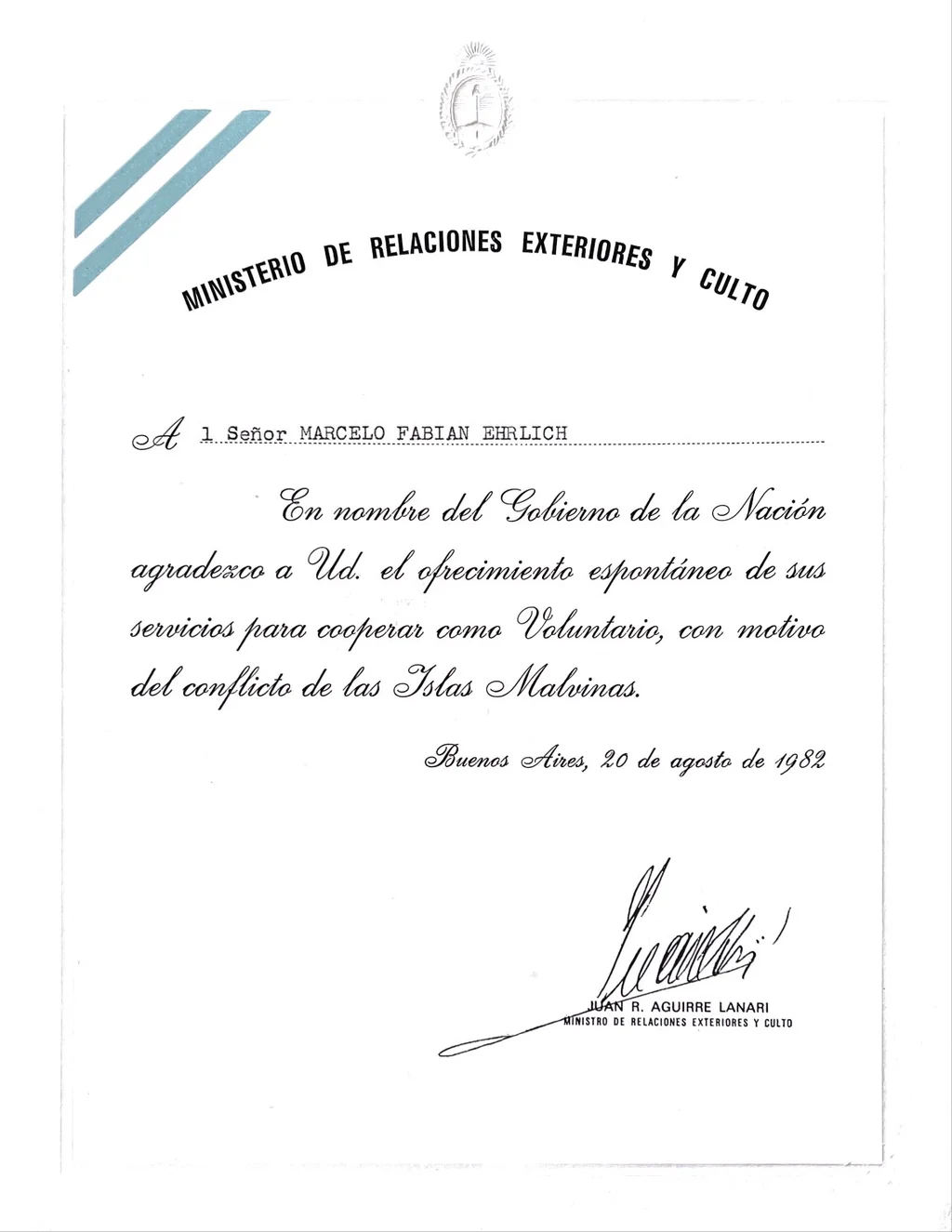

Rosadilla demystifies his personal actions and banishes any hint of heroism. She was looking for the possibility of helping in a practical way, although she believes that her contribution ended up being moral. In fact, the three of them are clear that at the end of the story they did a symbolic act and, to a large extent, that is what the Argentine dictatorial government recognized with the 763 greetings signed by the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship, Juan Aguirre Linari, on August 20, 1982, in which he thanked the spontaneous offer of services to cooperate as a volunteer due to the Malvinas Islands conflict.

Recognition of the Argentine government to those who enlisted spontaneously

Zimmer, Rosadilla and Martínez Larrechea – like the journalist Heraclio Labandera, then a medical student who enlisted to work for the Red Cross – disliked the regime that ruled from Buenos Aires. But all embraced the Argentine territorial cause and had their grounds for it.

The Uruguayan position rested on the firm pillars that the herrerista Carlo María Velázquez built in 1964 by matrixing the national position –and to a large extent Latin America– in the United Nations with a well-founded anti-colonial discourse.

Ambassador Velázquez, who also promoted Resolution 2065 (XX) of the General Assembly in 1965, was followed by Manuel Lessa Márquez, Baltasar Brum and other Uruguayan ambassadors to the international organization. The position, which clings to international law and the negotiated solution to the conflict, permeated Uruguayan diplomacy and in the last six decades it became a state foreign policy like few others. The fact that no government has ignored it is explained, to a certain extent, because the matter never managed to divide the waters of the Uruguayan political system.

In fact, in February 2012 the Malvinas Forum was born, an initiative that brought together dozens of Frente Amplios, Colorados, Blancos and (now) lobbyists around a cause. Among the members of this heterogeneous group there was a minister of Defense from the Front and a white mayor from Colonia who had volunteered to land in Malvinas in those days of 1982.