“I want to be a palm tree and climb the hill”, sing the palm trees, men and children who extract branches from palm trees in the El Ávila National Park, to give them to the faithful on Palm Sunday.

This tradition, of more than 250 years, is in the registry of good safeguarding practices of UNESCO and aspires to be World Heritage.

On Saturday, greeted by thousands of people, palmeros descend from the mountain with palms, crossing the exclusive neighborhood of Chacao to reach the church of San José de Chacao, where on Sunday this treasure will be shared with the devotees.

“We cry when we deliver the branches. It is incomparable. We feel it in our hearts.” This is how Carlos González, a 37-year-old carpenter, explains it.

250 years ago, yellow fever was devastating and Father Mohedano – the first parish priest of Chacao– asked the faithful to look for the branches in the mountains, promising to perpetuate the practice if the disease disappeared.

Carlos González and Álvaro Porras, 36, plunge into the forest followed by half a dozen young people to the place where they will camp.

About 300 palm trees are scattered in this national park to collect the branches of the palm, Caroxylum carifarum, an endangered species.

They search among trees they have planted. Before they cut palm trees at random, but with the risk of making them disappear, which would also have ended the tradition.

“Today we are palmeros 365 days a year. We plant, we clean the mountain. We do operations in other parks. We give back to nature what it gives us”, explains Álvaro.

the climb is hard

The “palmeritos” (little clappers) Santiago Coriat and Joseph Rincon, both 12 years old, are filled with fear and emotion.

“I’m a little bit nervous. It’s the first time,” says Santiago, who carries a backpack with food, a sleeping bag and a budare.

A load that will be too heavy for the child during the difficult ascent above 1,000 meters. Álvaro and Carlos carry about 60 kg on their backs.

They bring food, things to cook and sleep… Without forgetting “the vitamins”, some bottles of rum seasoned with pesgua (a mentholated mountain herb) to warm up and liven up the work, jokes Carlos.

The light from Caracas is enough to illuminate the steep path. At first wordy, everyone concentrates on their breathing. The conversations and the songs stop.

3H30. First stop to breathe. “The climb is hard but lowering the branches for the faithful, there is no comparable feeling when you see the joy of the people,” says Álvaro.

During the ascent, the group overtakes others who rest or let faster clappers pass. Some wear rosaries around their necks or T-shirts with the name of the event.

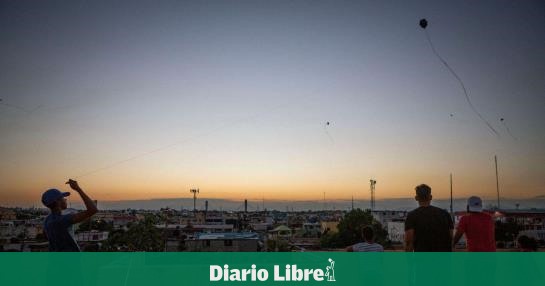

6H00. Dawn breaks and the group lies down to sleep a little in a viewpoint with a view of Caracas. Before resuming the ascent to the camp, where a small fire is lit and a snack is distributed accompanied by clouds of mosquitoes.

“There is faith, the responsibility to perpetuate tradition, but there is also friendship. Above we are united. We are all one”, explains Álvaro.

“The spirits of the deceased palm trees accompany us, we feel their presence,” says Carlos, a palm tree grower since he was 6 years old.

“We are happy”, say the clappers

The tradition, which excludes women, includes a campfire and jokes impregnated with some alcohol.

“What happens in the mountains, stays in the mountains”, jokes a palmer in his thirties.

The palm trees go in search of the branches. They trudge through the forest, climbing or descending steep walls, sometimes on all fours…

Álvaro teaches the youngest how to manipulate the palm trees without causing them damage and so that they can regenerate for the next year. Santiago and José are thus “baptized” by cutting their first branch.

On Saturday morning, after two nights in the mountains, they go down with the branches on their shoulders. For many, it is a kind of “stations of the cross”, a form of penance.

“We are happy to have accomplished the mission. No matter the pain or the tiredness, sums up Jean-Paul Blanco, tattoo artist.

To the sound of fanfares, rockets and accompanied by dancers, the palmeros parade through the city, passing in particular through a popular neighborhood called El Pedregal, where most of them come from.

“El Pedregal is a great family. Each neighbor has a common ancestor, “says Álvaro.

They make stops in front of the houses of deceased palmeros, where families hang portraits.

“It’s as if they were waiting for us at the door of their house,” says Carlos as he passes the home of an elderly man.

4:00 p.m. The clappers arrive at the church where the priest blesses the branches before placing them in the parish house.

It is the end of the adventure. Fatigue and emotion mix. They hug, they scream, they kiss, they cry, they laugh. “Mission accomplished”.