On Wednesday, July 31, 2002, the Uruguayan delegation that was in the United States (made of Ariel Davrieux, Isaac Alfie and Carlos Steneri), held one of the many meetings with representatives of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It was one of many meetings, but one of the most remembered by Steneri, who was Uruguay’s financial representative in Washington.

In short, the IMF representatives told the Uruguayans that the position was not to grant financial assistance to the country and that in a few more days a delegation from the organization would leave for Uruguay to begin drawing up an exit plan as they understood it should be done. “We didn’t say yes or no and we left. ‘We’re marching,’ I thought,’ he recalled.

After that lunch it was decided that Davrieux and Alfie would return to Montevideo. Another meeting had been arranged for the afternoon with the United States Department of the Treasury. “I was the one who stayed and I asked the Ambassador Hugo Fernandez Faingold to accompany me It was not customary for an ambassador to participate in economic meetings, but I asked him to come at least not to go alone,” Steneri told El Observador.

The meeting was with John Taylor, Undersecretary of the Treasury and already known by the Uruguayan representation. It was predictable what he would tell them. With the IMF’s refusal, there was little more to move forward. “We entered delivered, but we did not see it with a bad face. He was just like always,” she recounted. Taylor told them: “We have made every effort, but the situation is complicated.”

Steneri and Fernández Faingold listened waiting for the final blow. In Uruguay there was no money left, the bank run had been sudden and the reserves of the Central Bank (BCU) evaporated. A day earlier, on July 30, President Jorge Batlle had to decree a bank holiday that lasted five days. With that gloomy outlook on their shoulders, the two continued to listen to Taylor. “You had asked for US$2.5 billion, but it is not possible”, he told them by way of sentence. But to the astonishment of both, he continued: “We concluded that with US$ 1,500 million you cover the payment chain and the savings banks.”

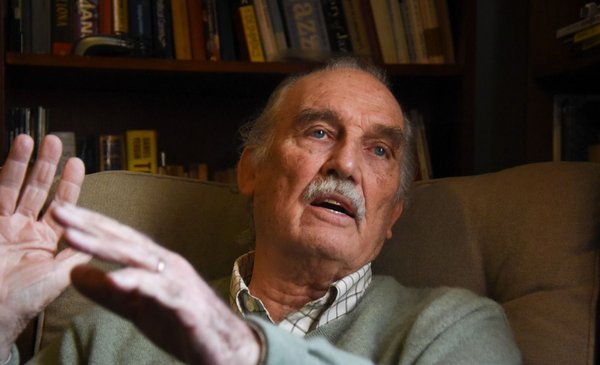

Camilo dos Santos

Steneri knew that to be true. The US$2.5 billion requested included 30- and 60-day term deposits. “We were engrossed,” she recalled. Taylor announced that the funds would be transferred that weekend so that the banks could open on Monday, August 5.

In his book On the Edge of the Abyss, published a decade ago, Steneri reproduced part of that dialogue.

Taylor: What do you think of the proposal? Well, if it is accepted, you have to act quickly.”

Our obvious answer in the affirmative was followed by the box question: And who will provide the resources?

Taylor: “The funds will come from the IMF through a new program.”

From the living room of his house 20 years later, Steneri added another part of the dialogue: “Our response was that a couple of hours ago the IMF had told us that there was no such program. Taylor responded: “Don’t worry, they’re going to call you on the phone.” And that happened later. They left the meeting in the Treasury walking fast and surprised. “It was our Maracana,” he maintained. The program with the IMF would be for the same amount and when the US$ 1,500 million were available, Uruguay would repay them to the United States government.

But to access this bridging loan was the commitment to approve a law to reprogram deposits in public banks, restructure the banking system and declare the bankruptcy of the Banco Montevideo, La Caja Bancaria, Banco Comercial and Banco de Credito. And that law had to be approved during that weekend for the banks to reopen on Monday, August 5.

Steneri had communicated with former president Julio María Sanguinetti who had assured him that the Colorado votes were there. It had also been confirmed by former president Luis Alberto Lacalle. Against the clock, on Sunday, August 4, the Banking System Stability Law was approved.

Between Thursday August 1 and the following week there were some meetings in which things got complicated again. The agency’s deputy managing director, Eduardo Aninat, said that the country’s devaluation in June had made the level of foreign debt unsustainable. While Steneri defended Uruguay’s position in Washington halls, Alfie and Horacio Bafico sent projections showing that the country’s problem was one of illiquidity, but not insolvency, something that countered the IMF’s position. After several days of negotiations, white smoke was achieved.

“Six months after that, Uruguay was back in the capital market. We proved that the strategy we proposed was feasible. The exchange rate began to appreciate rapidly. International investors confirmed confidence. Two years later he appeared UPM I”, concluded Steneri.

Hot dogs in a Washington tree

Those months of negotiation had their peculiarities. Many days had the Uruguayan delegation coming and going from the IMF headquarters to the halls of the Treasury Department. Some meetings were in the morning and others in the afternoon. It was very hot in Washington but that did not stop the formality of the suit and tie of the Uruguayan negotiators. But the impasses were different. “We would go out to the street with Davrieux, we would sit under a tree to eat some hot dogs that we bought from a cart; making time for the afternoon,” Steneri said. “We thought: if the people of Uruguay saw us. We were the mission that had been sent to the United States and we were under a tree with a can of Coca Cola and a hot dog. Then the photo comes out, at the formal dinner, but before that there is everything else, ”he summed up.

The outburst symptom

In March 2002 it began to be glimpsed that the economic crisis in Argentina could spill over into Uruguay. In previous years, Uruguay had presented itself to the markets as a stable financial center. This made many Argentine companies and depositors choose to have part of their deposits in the local banking system. But the crisis became unsustainable in Argentina and the dollars began to spurt out of the banks. But not only in front: it also happened in Uruguay. At the beginning of April 2002 the first symptoms of the crisis began to be noticed. The liquidity of Banco Comercial, Banco Montevideo, La Caja Obrera and Banco de Credito began to erode. The bullfight was beginning to settle in the local banks. Steneri recalled that in those days “the Argentines had taken practically all the deposits and the Uruguayans also began to run and take out the money.” There he maintained contacts with the Minister of Economy, Alberto Bensión, and in the conversations they concluded that Uruguay had to knock on the door of the US Treasury Department to request assistance.