I was walking this week down Corrientes Street when, poking around in a bookstore very close to 9 de Julio, I found a book whose 1955 edition seemed absolutely beautiful. 191 pages printed in the Lumen graphic workshops that no longer exist in Tucumán 2926. It is the novel bonjour sadness for which Françoise Sagan (1935-2004) won the French Critics Award at the age of 18. The translation corresponds to Noel Clarasó and the book was edited by José Janés a year after its publication in Paris, giving proof of the power of the Argentine publishing industry at that time. For that reason and the memory of an old anecdote, I bought it.

I had read the anecdote a long time ago and logically I had to review it in its original source to compose this chronicle. Actually, I had to go through all the sources to retrieve the fact. It happened in 1960 and began in Yara, then the Oriente province of Cuba.

It turns out that a Cuban journalist had just dismounted from a crowded dump truck. Fifty people standing. A good sun warming their skulls. Up and down paths in the Sierra Maestra. The group had traveled from Las Mercedes to Yara and was to continue on to Havana on a special train aboard which fifty international journalists had made the reverse journey after being transferred to the Havana station aboard 20 Cadillacs in a row. .

Still animated by the conversation in the dump truck, more excited than exhausted by the journey, the Cuban journalist finally finds himself near the station where he sees a girl who looks like Françoise Sagan to him. She is blonde, wears yellow pants and a beige shirt. She has hazel eyes. “She looks a lot like Françoise Sagan”, she thinks, adjusts her glasses and then, more than sure, says to herself: “she is Françoise Sagan”. He will soon write a chronicle titled “Pilgrimage to the Revolution” in which he explains her mental disorder at the time: “I had forgotten that she had come to Cuba sent by the newspaper L’Expressto review the celebrations of July 26”.

“You can’t imagine what a million people on a 10-kilometre road means, it’s unbelievable! It took us two hours to make our way in a rickety truck, overtaken by pedestrians, horsemen and American cars. Our instructions were not to separate. Some journalists left us anyway, passing out in the sun. We began to be hungry, and also thirsty, freedom.” Because, indeed, it was Françoise Sagan.

“In short, at 5 p.m., we find ourselves on a platform, 20 meters from the speakers, and in the middle of a sea of straw hats. (…) Suddenly, a roar: Castro was approaching. He is tall, strong, smiling, tired. Thanks to the telephoto lens of a kind photographer, I was able to contemplate it for a moment. He looks very well and very tired. The crowd shouted his name: “Fidel!” He looked at them with a mixture of concern and tenderness.”

Shortly after that impressive act had passed and she, like everyone else, had witnessed a crowd seduced by their hero, pampering him, spoiling him, listening to him.

“A million people had come in ten days, but a million people wanted to leave in the same half hour. It was a hell of a show. Night had fallen and our truck had traveled 10 meters in three hours. Exhausted by the sun, hunger and thirst, the Cubans and the journalists collapsed on the side of the road. For 10 kilometers, 20,000 cars, with their headlights on, honked their horns and sped forward, kicking up torrents of dust,” he writes.

But, at this moment, at the exact minute in which the Cuban journalist has discovered her, that 25-year-old girl is only trying to retain her feelings, the atmosphere she lives in to write what her compatriots will read later. “I am writing this article at 4 in the afternoon. The train has not moved. Some journalists have just arrived; they look funny and the conversation is weak.”

The then director of L’ExpressPhilippe Grumbach had entrusted him. bonjour sadness turned Sagan into a justifiably famous girl. Her early talent was consistent, her keen gaze, her maturity had allowed her to overcome her fair share of unpleasant incidents: a fail at “The Sorbonne,” a car accident in her Aston Martin. She shined as a chronicler and was in Cuba because of that shine. She, even she, has already written down the following: “It is the most incredible trip I have ever done and I hope I will do in my life”.

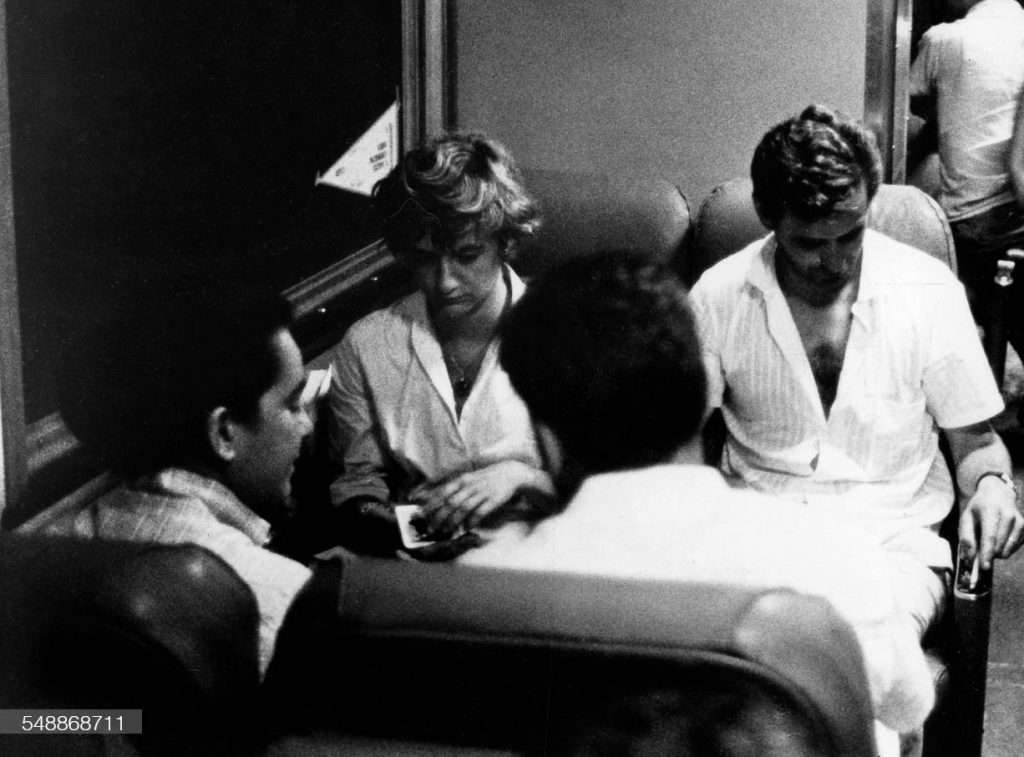

The Cuban journalist was struck by the group around him, all French. “They do nothing but sleep, play cards, lament that they are too far from the Saint Tropez spa, play cards, sleep.” Sagan, meanwhile, smudges the notebook and has added another idea: “A reporter from Match He tells me that in ten years he has never been on an expedition like this. If we go out, I’ll try to see Castro and talk a little more about Cuba. In any case, on July 26, 1961, I will spend it at home.”

The group of French in question was made up of that other journalist from paris match whom the Cuban would remember by his last name, Ferren. And this Ferren was accompanied by his wife and a photographer named Vital. Sagan’s brother is also there, but he doesn’t remember his name. When they board the special train and it sets off for Havana, the Cuban journalist is struck by the fact that the French want Cuba to define its policy before the journey ends: “With Moscow or with Washington. Choose, sir, we are not here to waste our time!”

“I explain to him as kindly as possible that Sartre spent a month in Cuba asking questions, taking notes, putting all his dialectical team into play and he still left without a precise, fixed idea about the Revolution,” says the Cuban journalist: “I don’t they understand. They don’t want to understand.” “Cuba is not so simple. Personally, I went away with the most romantic and enthusiastic ideas and came back with some reservations. I must say from the outset that I spent a total of nine days there, that I did not speak with Castro, that he was ill, and that I saw more people on the street than the government,” writes Sagan.

In Camagüey the special train had to make a stop to pick up provisions and the group of French, in addition to sleeping, playing cards and complaining about the distance from the Saint Tropez resort, insisted on getting off to see the city. A militiaman with a machine gun on his back and two Colts on his sides let them know that he couldn’t leave them. As he did not offer possibilities, one of the French shouted: “I am a free man!”, To which someone blurted out: “You come from a military dictatorship.” One of the French who has persisted, retorts: “I am not afraid. De Gaulle has also been elected by fourteen million votes. “How can I tell them that Hitler got the same amount,” says the Cuban journalist who observes how the same militiaman who has denied them the possibility of going down returns to offer the French some dry cakes.

“They seem to be completely unaware (I’m talking about the average Cuban) that they are an hour from the United States, that they have asked the Russians for help, and that this could be of interest to the world press. Finally, they are convinced that, apart from Russia, all peoples live under a horrible tyranny and that we French are lending a hand to a bloodthirsty executioner named de Gaulle. Conversations of this kind, if they continue, bring you to the brink of apoplexy. As for 1789, 1848, etc., you don’t know, we are backwards and cowards. I know that this kind of annoyance will seem childish, but you must have spent nine days with the Cubans.”

The reports written by Sagan on that revolutionary Cuba are not very encouraging for some of his countrymen on the left who had never set foot on the island. Much later, and according to another article in L’Express, said that he had found “too many soldiers, too many policemen everywhere”. “What also struck me was that this country was run by children. Bearded children, but children after all! And she pointed smiling: “I was a little crazy at the time. She thought above all about dancing, swimming, in short, party! ”.

The truth is that when the special train, mounted on special rails, pitching from right to left like an old ship (and obviously, like everything on the Island, a special one), arrived in Havana, Françoise Sagan was smart enough to having made a series of notes that are today part of his historic trip: “Cubans have preserved the sense of American propaganda, and everywhere there are only pamphlets, slogans, speeches, a hysteria of posters, professions of faith and, of course, barbarities. Everyone walks around with guns at their sides, pamphlets in their pockets and a formula in their mouths, which, moreover, looks very bad on the Cuban people, who are the kindest, most sympathetic and helpful people on earth.”

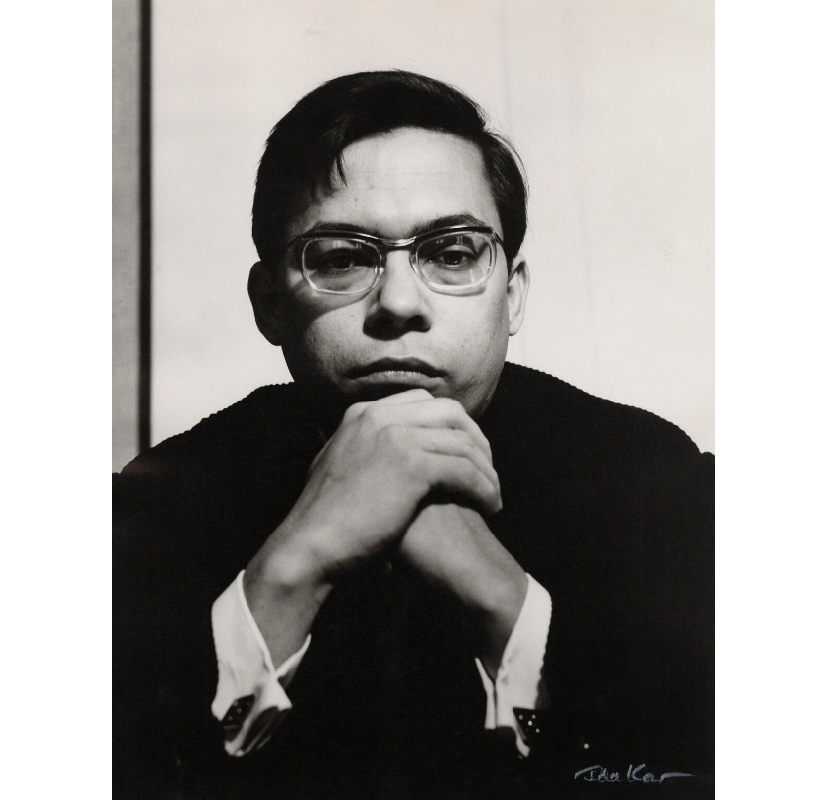

The Cuban journalist who also traveled on that special train was Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Sagan’s reporting for L’Express It is entitled: “Une promenade au soleil par Françoise Sagan”. The photos that I found of that moment, and of which I offer only details, correspond to the German Jochen Blume. Before this visit, a magazine directed by the Cuban journalist who was also the protagonist in this text had published these statements by Sagan about that obsession of those days called “writer’s commitment”: “The writer’s “commitment” is expressed through a series of practical attitudes, such as refusing to write in this or that publication. Politics for me is something purely utilitarian: it is about changing the world. But this has nothing to do with what I write, and I don’t think it matters much to the reader to be lectured, for example, about the social situation of my characters”.