The Argentine writer Abelardo Castillo (1935-1917) was summoned in 1967 for an anthology of short stories that would be published by Ediciones La Flor. A similar invitation received five other of his compatriots: Borges, Mujica Láinez, Sábato, David Viñas and Rodolfo Walsh.

The group is disparate in terms of style, social origin, political preferences, ages… But the anthologist did not need a directly revealing narration of their aesthetics from them; she just wanted an election whose result, as she writes in the brief presentation, was the closest thing to “a confirmation and a professorship.”

We find many hidden data in this anthology entitled The authors book that I recently came across when passing through one of the used bookstores on Corrientes street. The anthologist was the writer Pirí Lugones, granddaughter of the poet Leopoldo Lugones.

The son of Lugones and father of Pirí, whose real name was Susana Lugones Aguirre, is credited with the invention, or at least the extension in use, of a macabre instrument designed to apply powerful electric shocks to the most vulnerable parts of the human body. It was created during the dictatorship of José Benito Uriburu in the 1930s.

A few years after the publication of this 175-page book, which came out of the printer in July, Pirí, who was a member of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (Peronistas) and later in Montoneros, suffered the effects of another dictatorship in the so-called National Reorganization Process, which had General Videla at the head. She was kidnapped, tortured, and her body is now on the list of missing persons for the period.

Tales with macabre or violent aspects predominate in the book and, in addition to testing the preferences of the writers summoned to choose a story from universal literature, the very deliberation of the authors reveals the intention of the anthologist to give them the floor so that tell why they chose the texts we read today.

Borges, who opens with the story wakefieldby Nathaniel Hawtorne, argues that this story “as a behavioral fantasy, as a pathetic study of human possibilities, anticipates the Bartleby of Herman Melville and the inventions of Kafka”; while Sábato opts precisely for Melville and his Bartleby because “a truly revolutionary writer is the one who offers us a new vision of reality.”

Mujica Láinez opts for the The Dunwich Terror by Howard Phillips Lovecraft, since the author “has managed to create a whole new mythology of horror, with worlds and other worlds that have nothing to do with those that man continues to seek at unprecedented heights and into which only he has dared to enter ”.

Viñas elaborates when explaining the reasons that make him choose The slaughterhouse, by Esteban Echevarría, favored among his readings because he fervently believed that the Argentine narrative began in this story and because in it “the fundamental lines of the basic situation of the writer are outlined.”

Walsh opts for The anger of an individual, anonymous short story from China, which he brings up because of his “bias in favor of short literature” and “in favor of useful literature”; while Abelardo Castillo presents us The little Mermaid, story that is second of the anthology.

For Castillo there are no exact reasons for his selection. Maybe doubt. He says he is aware that by preferring this he had abolished ten or twenty of the most splendid known tales, but he considers it appropriate to propose what seems like a work for infants, according to the versions made later from the film industry itself and with brands such as Disney .

Castillo wrote:The little Mermaid It is the only love story in the world, that Juliet Capulet, next to this little fish, is something like the Bearded woman”.

In this sense, the original story by the Danish Hans Christian Andersen, published in 1837, seems “irreverent” to him, and he honestly warns that he has taken the liberty of making the story end where its author should have ended: without moralistic phrases, without lessons. for posterity; alluding to death when death is what the story asks for in exchange for happiness, and putting ourselves in front of pain when pain is.

The sea in the story is the kingdom, the homeland, “the ideal place”, until the character finds on the other side of the surface, in an unknown and mysterious environment, a greater attraction. To materialize the love that he has experienced and believes to be reciprocated, he must pay, and in what way: regardless of the most beloved talents, he will lose his voice and suffer with each new step with his new legs.

“I will bear them!” said The Little Mermaid with a trembling voice, thinking of the prince and the immortal soul.

But things do not turn out as she envisioned. She without a voice and with legs, she is not recognized. She is doomed, but she still has a chance: The Little Mermaid, to stay alive and regain her former life, she must get rid of the reason that had made her leave her world: she must kill the prince. She takes a knife, approaches the bed where he sleeps with his new wife, and hesitates.

“I run the risk of looking like an upside-down eccentric. Perhaps I am becoming the original, the rare one, ”Castillo writes to justify his choice:“ The search for an immortal soul worries me and The Little Mermaid in particular, and humanity in general, it seems emphatic to me ”.

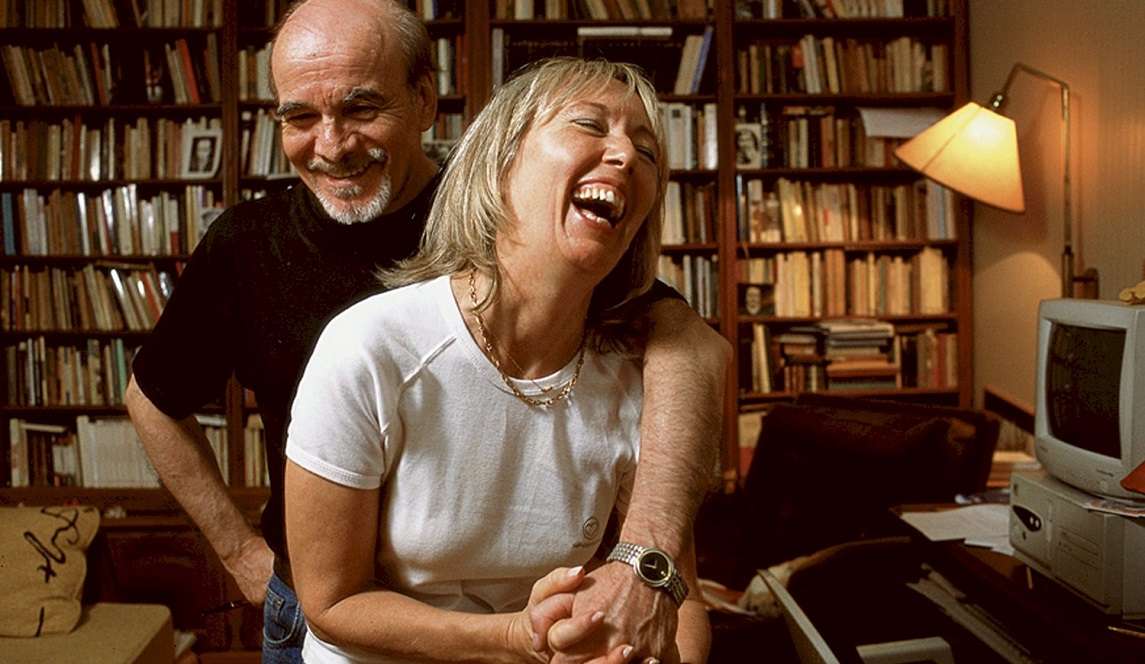

Those who have studied and read the work of Abelardo Castillo well comment that in his second novel, The one who is thirsty (1985), identifies his wife, also a writer Sylvia Iparraguirre, as The Little Mermaid; that there is a story, or a fragment of a diary of hers, in which she wrote: “I know that she is a mermaid, although she walks on two legs. I know it because inside her eyes there is a path of dunes that leads to the sea ”.