By Christian Nielsen

Coins that our great-great-grandparents used in their daily lives. The history of the coins that preceded the Guaraní goes back to the Spanish colonization. The most valid was the real, which circulated throughout the Hispanic world between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In 1811, Paraguay still did not have enough institutions to issue its own currency. So, not only the real continued to be used, but also the old Spanish peso, known as the “real de a ocho” and sometimes as the strong peso. The cuartillo also ran, a coin minted in vellón, an alloy of copper and silver, put into circulation in the times of Enrique IV of Castile, in the fifteenth century, with the value of a quarter of a real. All these pieces were minted in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which had an abundant supply of precious metals in Mexico and Venezuela.

Many Paraguayans from the last stage of the colony and the first stage of independent life preferred to store their funds in “carloscuartos”, a four-real coin minted in 1792 in Potosí, Upper Peru, with the effigy of King Carlos IV.

PAPER MONEY – The era of paper money began on March 1, 1847 when the government of Carlos Antonio López authorized the issuance of the peso in series of bills of one, three, five, nine and twenty pesos.

As reported by Luis P. Frescura in his history of the Paraguayan monetary system, the first issue of national banknotes was made for a total of 200,000 pesos “of legal tender”. As until then, apart from the real and the cuartillo, the ounce of gold and the strong silver peso circulated, the parity established from the first issue was: one ounce of gold equal to sixteen paper pesos and one strong peso was equivalent to one paper peso. .

As for the metal coins, the Spanish expert Adolfo Ruiz Calleja relates in his blognumismatico.com, that “the coins issued -during the government of CA López- were pieces of one twelfth of a real and weighed 6 grams”.

The design of this currency continued to be in force long after, even after the appearance of the Guarani. Says Ruiz Calleja: “On the obverse they represent a laureate scene where a lion with a radiant Phrygian cap can be seen; the reverse shows the value of the coin, the country and the date. These coins were commissioned by Paraguay from the Soho Mint (Birmingham, England), which manufactured fractional currency for many other countries and colonies in the mid-19th century.”

AFTER THE WAR STORM – After the war against the Triple Alliance, with the country in ruins, its economy devastated and the population decimated, the currency issued by Don Carlos ceased to be valid. What replaced it? Freshness is painfully didactic in describing the actions taken by the authorities at the time.

“In order to obtain financial resources -says the Paraguayan historian- the post-bellum governments, faced with public and private poverty, had no choice but to appeal to the comfortable discretion of issuing paper money, since the year 1870. These issues were made in the early days, based on its convertibility at par with gold. For this, special resources were allocated, such as the proceeds from the sale of the State railway, public lands, government buildings, the tobacconist’s, salt, soap, various taxes and even probable loans.

But the end of this new issue was foreseeable and from then on coins of other origins began to be taken as a value reference. Frescura lists that the Spanish ounce was worth 16.50 pesos, the Mexican 16.30, the Brazilian coin of 20 milreis 16.25 and the Chilean condor, 9.50. Also circulating were the Spanish doubloon and the US dollar at 5.10 each, the pound sterling at 5, the Swedish carolus at 2, and the German mark at 4 pesos. You could even get a Peruvian sol at a rate of 20 pesos per unit.

THE PESO IS REVALUATED – Fernando Masi and Dionisio Borda made it clear in their work “State and economy in Paraguay. 1870-2010”, that the recovery of Paraguay after the 1970 war took place with “a simple recipe, but, in those years, almost unquestionable: foreign capital inflows, external financing to rebuild the fiscal coffers, and all kinds of stimuli for European immigration.

Exports of packaged meat, yerbamate, salted hides, and the red quebracho extract known as tannin strengthened the economy. This last product began to acquire a very high market value. Masi and Borda relate it:

“By 1920, the nominal market value of Paraguayan exports was almost three times higher than in 1913. The quebracho industry became the main generator of foreign exchange. Such was the impact of this boom that the Paraguayan paper money appreciated considerably, going from about 38.7 pesos per stamped gold in 1915, to 18.6 pesos in 1916”.

The backing of value was given by the strengthening and health of the economy at that time.

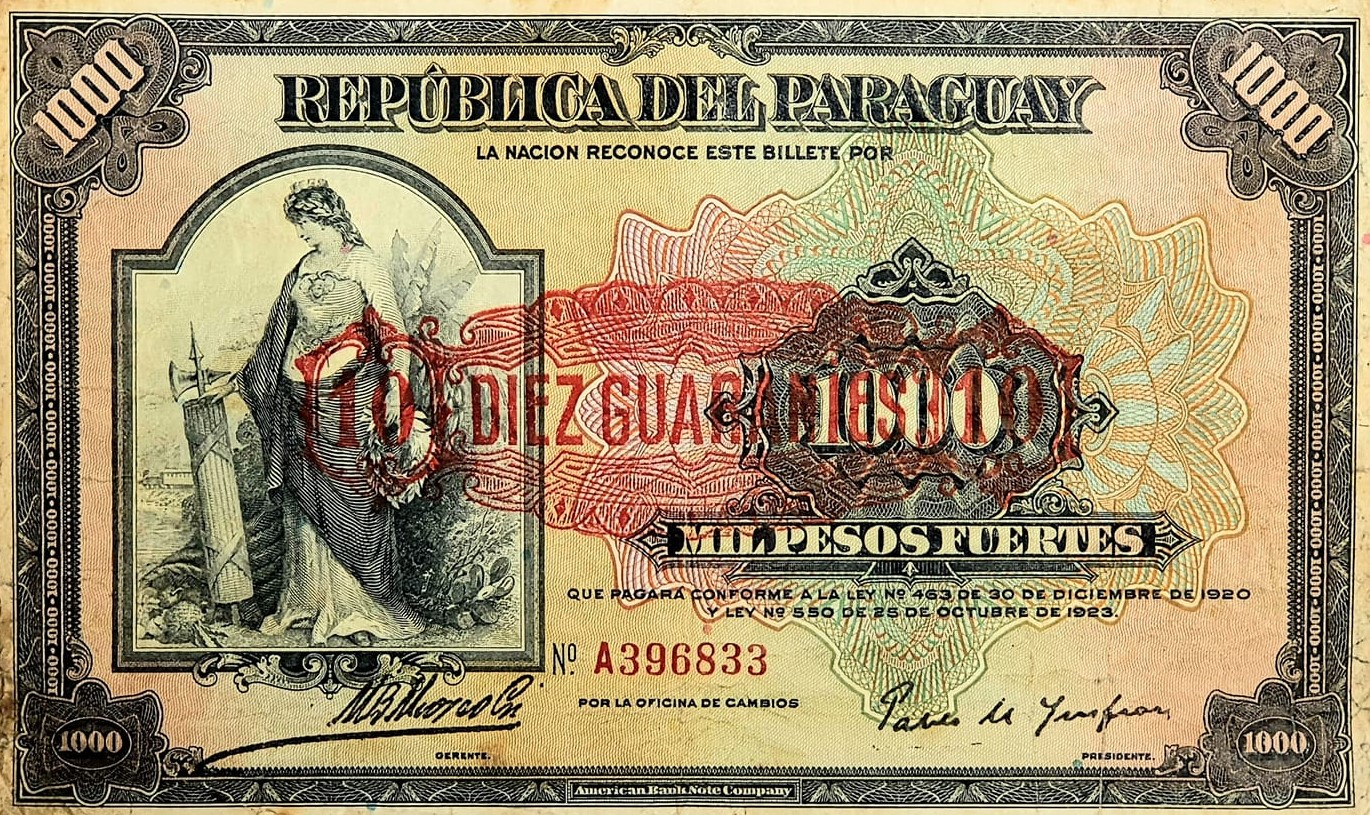

THE GUARANÍ APPEARS – In 1944 there was a monetary reform that gave rise to the appearance of the Guaraní. The first banknotes of the new currency were, in fact, old resealed pesos until in 1952, with the creation of the Central Bank of Paraguay, the first printed banknotes circulated in the house of Thomas de la Rue in London.

Since then, the Guaraní has accompanied us through decades of stability, turbulence and violent fluctuations in the regional economy. In that period, Argentina changed its currency name three times by removing 13 zeros from its original peso. Today, the guaraní is preferred as a reserve of value in the Argentine border areas over the battered peso that has not finished falling.

Times and customs, according to Cicero.