After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Yuriy Makeyev was left homeless and jobless, a combination of circumstances that left him on the brink of a nervous breakdown.

The 48-year-old, who left his home in the war-torn east of the country, hopes to return to normalcy thanks to a special course in psychological rehabilitation at a kyiv clinic.

At least 5,000 civilians have been killed and as many wounded since Russian President Vladimir Putin sent troops into Ukraine on February 24, according to the latest UN figures.

But those who survived the devastating bombings across the country suffer from psychological trauma.

Psychologists say that spending weeks in bomb shelters, as well as losing your job and having to leave your home, can cause a level of stress and frustration that is difficult to overcome without help.

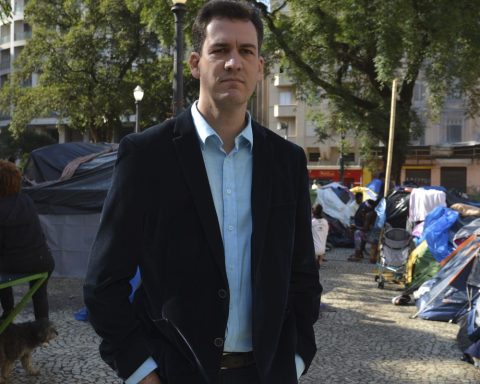

“After the outbreak of the war, I was simultaneously homeless and jobless,” said Makeyev, who worked as a magazine editor in kyiv.

His ordeal began in 2014 when he had to leave the city of Donetsk, in eastern Ukraine, conquered by pro-Russian separatists.

“What happens in kyiv and surroundings, I already saw in Donetsk. I didn’t want to experience it again, but it happened,” he said.

A Russian missile attack on a residential building in kyiv left one person dead in June.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, Makeyev’s magazine closed and he became unemployed.

The hostel where he lived also closed and with the financial difficulties, he could not rent elsewhere.

“Various factors caused continuous stress and I urgently needed something to deal with it,” Makeyev said.

social demand

He told his story to AFP sitting on a bench in the courtyard of the “Socioterapia” psychological rehabilitation clinic.

“There are a lot of people with post-traumatic stress disorder,” said Denys Starkov, a psychologist at the crisis center, which opened in June.

“There is social demand, psychologists are overloaded with these clients, so this idea came” from the clinic, Starkov added.

It offers a special three-week course focused on group sessions for people who suffer from anxiety, panic attacks or painful memories.

Some, like Makeyev, come straight to the clinic, others call a helpline and talk to specialists, who determine if they can get the therapy.

Treatment is free. The course includes 15 thematic sessions aimed at understanding the experience of trauma and learning ways to cope with it.

“If the (syndrome) is not treated in time, it takes more severe forms,” said Starkov, sitting in a large room with rows of chairs for group sessions.

The three-story building on the outskirts of the city served as a hospital for drug and alcohol addicts before the Russian invasion.

Now a team of psychologists conduct sessions with patients several times a day, both in groups and individually, said Oleg Olishevsky, head of the therapy program.

He specified that there are currently 10 patients in the course, but the center plans to increase it to 30.

“In the next 10-15 years, this will be the main area of work because every inhabitant of our country experiences this traumatic situation,” he told AFP.

Still, Olishevsky and his team are optimistic.

“We are already seeing the results. People feel that they are safe here, that they are being taken care of,” he said.

The Makeyev patient seems to agree, despite having only four days in the clinic.

“I feel inspired here. They gave me hope that I had lost,” he said, dressed in blue pants and a white shirt.

The first thing he wants to do after finishing therapy is look for a job, according to Makeyev.

“I hope to leave here with emotional balance, and I’m not afraid to say it: as a happy, joyful, optimistic person,” Makeyev said, a trace of a smile on his face.