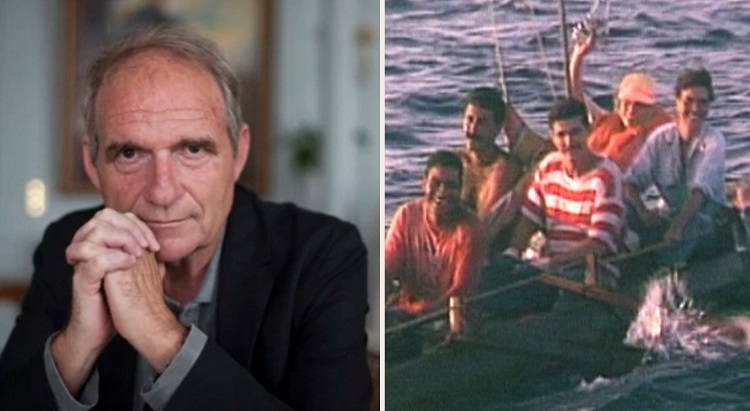

MADRID, Spain.- In 2002, the documentary feature film raftersby the Catalan director and journalist Carles Bosch. raftersnominated for the Oscar and Goya awards, winner of the Emmy in the photography section, is an approach to the story of seven Cuban migrants since they left Cuba on rafts during the mass exodus that occurred in 1994, the time they spent at the Guantánamo Naval Base after being intercepted at sea, and their subsequent arrival in the United States.

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the premiere of the documentary, fully valid despite the passage of time, CubaNet spoke with Carles Bosch, also the author of works such as Septembers Y petite.

How did the idea for the documentary come about?

―In August 1994 I was on vacation in the Dominican Republic, when a story broke that was on the front page of all the newspapers in the world almost at the same level as what is happening in Ukraine today. That for the first time the Cuban regime told the people “whoever wants to leave, let them leave” was logically news. And that having said this there were thousands of people building rafts with the material they had at hand, because it automatically became news.

I received a call from TV-3 (Televisión Catalana) for which I was working at the time, and it was decided that I should go quickly to Cuba.

The same day I contacted friends, some linked to the world of audiovisuals. I was lucky to contact Camilo, a Cuban cameraman willing to work. The same day I was able to send chronicles for the television of Catalonia and other televisions.

So I told them, “I have a feeling this is fat, send me a cameraman.” The cameraman they sent was Josep María Domènech, who over the years would win the Emmy in the category of Best Photography with this material.

A few days later, the Clinton administration announced that it would change the permissive law regarding the Cuban who arrived. (Persons intercepted at sea would be deported to the Guantanamo Naval Base.) The rafters’ crisis theoretically ended here, but in truth it did not end, because more than 20,000 Cubans would be stranded in Guantánamo.

Those who were already in Guantánamo had risked their lives, they did not know what would happen in the job they had left behind, or if the house they had left behind had been taken over by the State.

We returned to Barcelona with all this material and edited a first report, which was called “Aventuras sin fin”.

In fact, the last image I had was of the character of Merisis, who we stopped filming at sea. Merisis leaves knowing that they were sending the rafters to Guantánamo and still leaves.

Upon arriving in Barcelona, I received a message from the Cuban cameraman informing me that Merisis had returned to land, because her raft had broken down. And I tell him: “Camilo, go to his house…”. Camilo manages to send me the images and we can include him in the first report.

A short time later I obtained permits to go to Guantánamo and I asked my Television for permission to do a second report, which was called “Dear family”. And then a third when some are taken from Guantánamo to the United States.

The fact that two years after starting to shoot, when the rafters already had one foot in the United States, I thought that my work as a journalist had ended, means that I still did not understand anything. This was not emigrating, emigration starts from there. It is after the years when you can begin to value what you have bet, which is not just crossing a few miles of sea.

Then I realized that I could make a feature film about it. To make matters worse, Cubans are very attractive in front of the camera, and they also go to the United States, which could not be more cinematographic.

Three television reports and a lot of chronicles had come out of it. I had kept everything to myself, and five years later when I begin to find out what is happening with them, I think: “There is a movie”.

―There are seven protagonists in your documentary, but it was a situation that thousands of Cubans were experiencing. How did you choose them to be the protagonists?

―Those seven characters are representative; It is a choral documentary with different protagonists who walk in the same direction. There is no bolero singer or ball player there. The important thing is when people leave the cinema and do not say: “I have seen the story of seven Cubans.” She says: “I have seen the story of thousands of Cubans.”

That is why the film after so many years is still seen at festivals about emigration, because it is presented as a theme, unfortunately, universal.

-What was your reaction when you know that you are going to be recorded?

―When people are experiencing such transcendental moments in their lives, they usually allow themselves to be filmed. They were on an adventure. We act like other journalists they saw. I assure you that during the whole process there was no difficulty in this regard. I myself was very surprised when I arrived at Guantánamo. It was a surprise to me how well they received me.

In Guantánamo I could spend 15 minutes with each of them. When we journalists go to Cuba we act as messengers. Contact between Cuba and the diaspora has not always been easy. Let’s not say between those who are in Guantánamo and their family. The role of those who travel between the island and the continent is almost part of the Cuban reality.

―Permissions to film in Cuba…

―In Cuba I obtained permits, but not only me, almost any journalist obtained permits. Fidel and his government were interested… He knew there were going to be 30,000 people. Fidel knew perfectly well that Florida was not prepared to receive that number of undocumented people and it was in the Cuban government’s interest for this to become an event. The proof is that the Red Cross is interested, Human Rights Watch is interested, and what the Cuban Government wanted to happen happens, which was: “We are going to make a movement so that the United States Government changes its policy on that superior permissibility that has the Cuban who arrives on the shores of Florida”.

―How do you manage to stay in contact with them after so much time and with so many changes of cities?

“In one way or another, we had the possibility of being in contact with all of them. With Merisis, for example, I kept in touch because we were sending her some creams for a skin problem.

―For the making of the documentary you spend a lot of time in contact with these people and witness how there are mothers who leave their children, marriages that separate, etc. What do I mean to you?

“There are very emotional moments for me. The whole process of the film marked me. During the filming I sometimes kept a certain distance. Friendship arises more when everything is over. The stories we experienced were exciting. Juan Carlos, for example, moved me when he met him years later and told me: “Thank God I have been able to succeed and I have been able to send a refrigerator to my mother, the most beautiful woman in the world.”

―Is there any fiction in the documentary?

-No, I militate a lot against cheating, first because it shows. The traps imply that something of what is happening did not happen, and for me that is already fiction. It is so impossible for real characters to act… When there are falsehoods, they are noticed.

“Oscar nomination…

“In the Oscar race the rules are super complicated. Academics vote; nobody knew me. True, the film had worked. The fact that a film touched on the Cuban-American theme, that had won in both Havana and Miami, caught the attention of HBO and the Sundance festival, and we began to have awards.

You are eligible for the Oscars if the film has been released in North American theaters. And when HBO buys it, when he sees the reaction of the public at Sundance he says, “this film can have a circulation in theaters.” (…) Then they call me from New York and tell me: “We are going to play hard, your film can aspire to the Oscars.”

When it became known that we were nominated, I was presenting the film in Boston. Juan Carlos was with me, because we knew we were in the short listwhich is a list of 25 finalists that is done a bit to say “start preparing”.

Of the 25 who were in the short list the first they say is ours. The moment they give the name they all go crazy, there were shouts and hugs. I cried. I had fought for the film. Not always in Cuba they let me film as I would have liked. Not always in Guantánamo they let me film as I would have liked. It wasn’t easy to push forward.

―Currently the figures for Cuban migration are similar to those of Mariel and higher than those of 1994. Did you imagine that the documentary could be so valid 30 years after it was made?

―If the current figures are similar to those of Mariel, I don’t know. I know that the economic difficulties are very big. That in Cuba right now there are figures of people who want to leave the country does not surprise me. If the economic situation is so desperate, I’m not surprised.

Thirty years ago I had no idea what would be happening in Cuba today. I did not know that I would continue with a socialist regime where some things work and others absolutely do not.

Receive information from CubaNet on your cell phone through WhatsApp. Send us a message with the word “CUBA” on the phone +1 (786) 316-2072, You can also subscribe to our electronic newsletter by giving click here.