After the July 28 elections in Venezuela, state actors used Telegram channels and other social networks to pursue and reveal the personal information of opponents of the government of Nicolás Maduro

Chronicle One, Fake News HuntersCivil Monitor

“They’re looking for you!” “You have to leave the country!” The first alert messages arrived on Raúl*’s phone on July 31, 2024, three days after the National Electoral Council (CNE) of Venezuela proclaimed the re-election of President Nicolás Maduro. In those days, national and international observers, other countries and international organizations were severely questioning the official results announced. In addition, protests broke out inside and outside the country to recognize the victory of the opposition.

“I became very paranoid, to the point that I had to throw away my phone. “I had the feeling that someone was listening to my calls,” Raúl later told this journalistic team.

Raúl assures that he did not participate in riots, he was a citizen observer of the electoral records at his voting center. He ended up imprisoned after being the victim of a digital harassment campaign linked to members of the Venezuelan government.

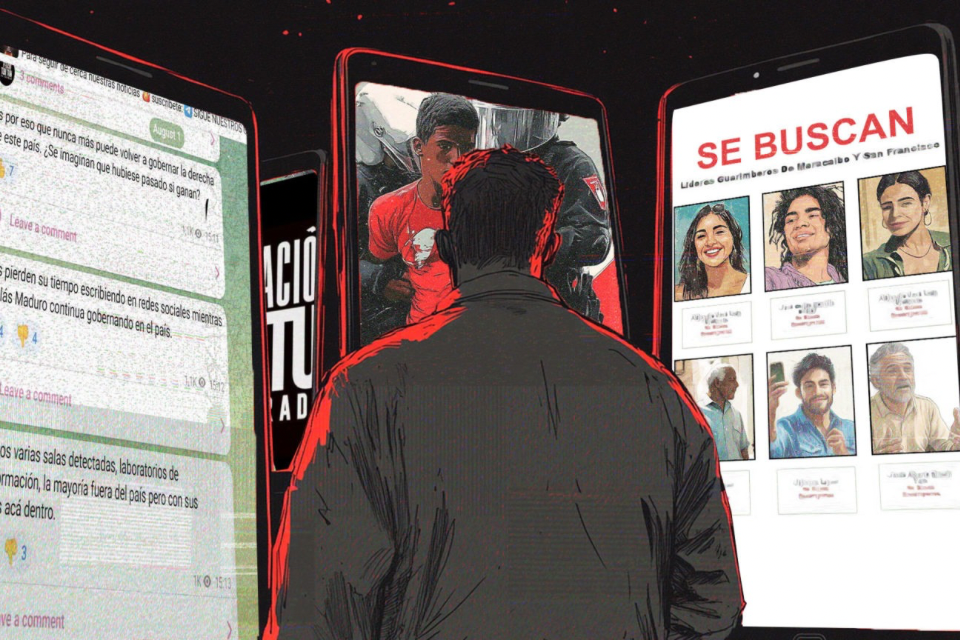

His photograph, name and identification document number appeared along with the information of other men and women in his town, in an image where it reads in large: “WANTED.” They were designated as “guarimbero leaders,” a term used by the Maduro government to refer to opposition protesters.

*Read also: Political prisoners of La Crisálida are prohibited from visiting, relatives denounce

He was also seen in an image of a WhatsApp group of members of the ruling Venezuelan United Socialist Party (PSUV) in his community, called “Compañeros Psuv”, and in an anonymous account on Instagram, where he was described as a “terrorist”.

Like Raúl, dozens of young people, political leaders, social and community leaders, or civilians who fulfilled their role as electoral observers or went out to protest, have been publicly exposed on social networks.

This investigative alliance managed to identify twelve cases of this style. These are people whose data was disseminated on social media profiles linked to the Venezuelan government, are political activists or went out to protest after the announcement of the election result, and ended up in a detention center while the regime carried out the “Operation Tun Tun”as the Madurismo has called the widespread campaign of arrests that according to international human rights organizations are arbitrary. Another 16 citizens remain protected and two are exiled.

“I don’t want to leave the country, I have my life here and I want to continue doing political life (…) Why me? … I am not a criminal,” Raúl questions.

But this campaign was not a spontaneous initiative among government supporters. On the contrary, it involved interaction between state actors and collective efforts at doxing, the technical term for the dissemination of someone’s personal data online without their consent.

For Marino Alvarado, coordinator of the Venezuelan Action Education Program (Provea), an organization that promotes human rights, it is a “policy of State terrorism” where any allegedly suspicious person “is at the mercy of the whim and arbitrariness of any police body.” ”.

This journalistic investigation compiles traces and reconstructs events recorded online starting on July 28, from when 1,824 arrests have been recorded until October 25, including 69 minors, according to the organization Foro Penal, which provides legal assistance to detained people. arbitrarily and to their families.

It is the result of journalistic collaboration The Illusionistsa project coordinated by the Latin American Center for Journalistic Research (CLIP), in which reporters and digital researchers from 15 media outlets and organizations in Latin America collaboratively investigate the circulation of false information and the manipulation of public conversation in digital media, during this “super electoral year” of 2024 in Latin America.

Identify and isolate the enemy of the government

“I need you to search #telegram for the #CazaGuarimbas group and report it. “They are hunting those who come out to demonstrate URGENTLY!!!!” Complaints like this began to go viral on social networks since July 30, while pro-government civil groups in the streets, armed, terrorizing people and dispersing public events with bullets.

The Telegram channel @CazaGuarimbas was promoted among digital spaces of followers of the Venezuelan government, exposing opponents behind the slogan: “NO TO FASCISM. NO TO VIOLENCE.” And although, as we demonstrate here in detail later, @CazaGuarimbas, now deleted, was the first, it is not the only channel created to “hunt” dissident voices.

According to the analysis of this alliance, Telegram, the instant messaging application of Russian origin, is one of the main platforms from which this campaign was articulated and featured the largest number of actors promoting it.

A follow-up to the timestamps that each publication leaves revealed that @CazaGuarimbas was the first group on Telegram in which personal information of people who demonstrated against Maduro was shared, in an organized and systematic way, being the heart of the doxing campaign. which lasted for several weeks.

The first publication on @CazaGuarimbas was made on July 30, 2024 at 01:11 am Venezuela time and, in just seconds It was forwarded by one of its administrators to @CpnbDaet, the official Telegram channel of the Directorate of Strategic and Tactical Actions (DAET) of the Bolivarian National Police Corps (CPNB).

Between July 30 and 31, 86 messages from @CazaGuarimbas were forwarded to @CpnbDaet, which highlights the coordination between both channels and suggests that @CazaGuarimbas functioned as a kind of “auxiliary” channel where the DAET was centralizing accusations.

TO 10:43 am, the link to the Telegram channel @CazaGuarimbas was published in the CC200 mobile application, an internal online electoral organization system of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV).

Various accounts on social networks (1, 2, 3) documented, with screenshots, that this link had been shared on the internal communication channel of Nicolás Maduro’s “Venezuela Nuestra” Campaign Command, in CC200.

“We have created this link to report terrorist, fascist actions (guarimbas) in any part of the national territory,” said the message published in the app, followed by the link to the channel @CazaGuarimbas, which also requested the sending of photos or videos .

Another version of the same message, shared on Xformerly Twitter, and that had gone viral on WhatsAppattributed the text to “Pedro Infante” instead of CC200, a name that coincides with that of the PSUV Vice President of Organization, Pedro Infante Aparicio. Despite this coincidence, the investigation could not independently verify that the text came from the same person.

The message reached thousands of PSUV militants and members of its organizational structures throughout the country and, in a couple of days, the Telegram channel had accumulated more than 21 thousand followers.

Users on other social networks warned about the danger and began to ask that it be reported.

He July 31 at 01:41.@CazaGuarimbas administrators shared links to two new backup channels: @ContraLasGuarimbas and @CazaGuarimbasVe, where they began sharing forwarded content from the original channel.

On July 30, the official DAET channel, @CpnbDaet, associated a discussion group with the channel, called @SeBuscan, which continued to receive reports about protesters in the streets, as had been done with @CazaGuarimbas.

Both the channel and the group, both linked to the substructure of the Bolivarian National Police, share an administrator. Some of its users are police officers according to the same descriptions in their profiles.

“I know where one of the guarimberos lives in Mérida (…) Last night he was burning rubber (tires).” A few hours after the creation of the @SeBuscan group, users began to activate.

“Comrades, be specific,” wrote the administrator of said group at 10:43 that day. He then clarified the way in which the information is received. “Write in a single message: complaint, place and photograph.”

Complaint, location and photograph. While group member users sent their reports, the @SeBuscan administrator did the same, forwarding content from @CpnbDaet and vice versa.

Always a photograph. In some cases, a video. Full names, family members or places of work. Where they live and even phone numbers are some of the personal data revealed in these chats.

On several occasions, the victims are very young, at least in appearance, teenagers.

At 8:30 p.m. that same day, official Government accounts in instagram, Facebook and Threads They shared links to the @SeBuscan group.

“Citizen security organizations ask for the support of citizens to identify the men and women responsible for extreme violence. If you know someone who is violent, you can send it through that means,” says one of the government publications.

“After two months of being hidden, I can tell you the situation that has been happening to me.” tells on Instagram journalist Luis Gonzalo Pérez, from the communications team of opposition leader María Corina Machado and presidential candidate Edmundo González.

Exile, he says, was not something he expected, but he ultimately deemed it necessary to safeguard his family.

As of July 28, he began to receive threats from state security agencies. He also received messages warning about his personal data that was circulating on the internet.

As if he were a criminal, Luis’s photograph was sent along with a reward notice on the DAET’s Telegram channel, where they accused him of “paying minors and selling drugs to motorists”, supposedly present in the demonstrations rejecting Maduro’s re-election.

To read the complete information click here

Post Views: 1,086