September 16, 2022, 2:38 PM

September 16, 2022, 2:38 PM

A group of researchers has discovered a heart of 380 million years preserved inside a fish fossilized prehistoric

They assure that the specimen represents a key moment in the evolution of the organ responsible for pumping blood and that it is found in all animals with a backbone, including humans.

The heart belonged to a fish known as gogonasuswhich is now extinct.

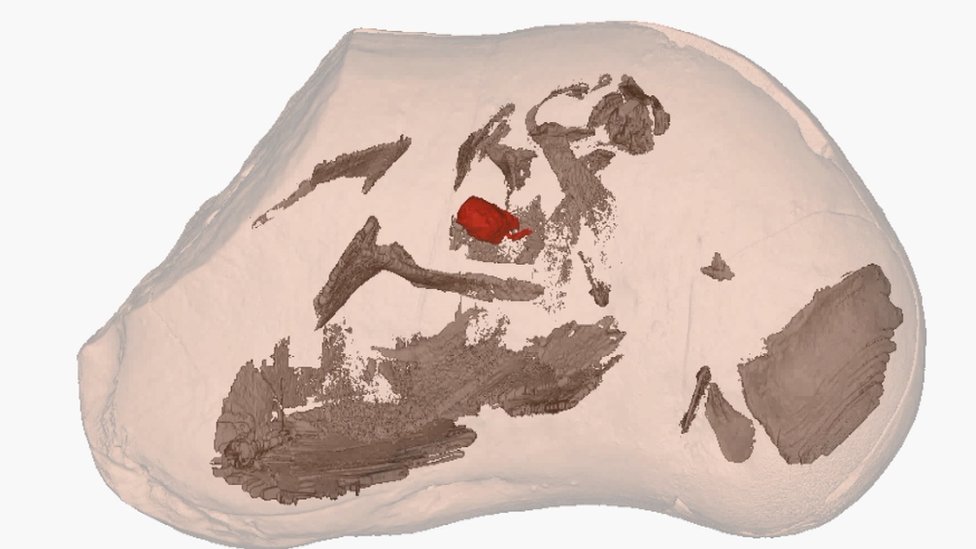

The finding described as “amazing” and published by the magazine Sciencewas made in Australia.

Scientist and professor Kate Trinajstic of Curtin University in Perth told the BBC about the moment she and her colleagues realized they had just made the biggest discovery of their lives.

“We were huddled around the computer and we recognized that there was a heart and we almost couldn’t believe it. It was incredibly exciting,” he said.

Usually it is the bones rather than the soft tissues that become fossils, but at this site in Kimberley, Australia, many of the fish’s internal organs, such as the liver, stomach, intestine and heart.

“This is a crucial moment (to understand) our own evolution,” said Professor Trinajstic.

“It shows the body plan that we have evolved from very early on, and we see it for the first time in these fossils,” he added.

“Amazing and amazing”

His colleague, Professor John Long of Flinders University in Adelaide, described the find as “a amazing and amazing“.

“Nothing has ever been known about the soft organs of such ancient animals, until now.”

The fish gogonasus it is the first of a class of prehistoric fish called placoderms.

They are the first fish to have jaws and teeth. Before them, fish were no longer than 30 cm, but placoderms could grow up to 9 meters long.

Placoderms were the dominant life form on the planet for 60 million years. They existed for more than 100 million years before the first dinosaurs They walk the Earth.

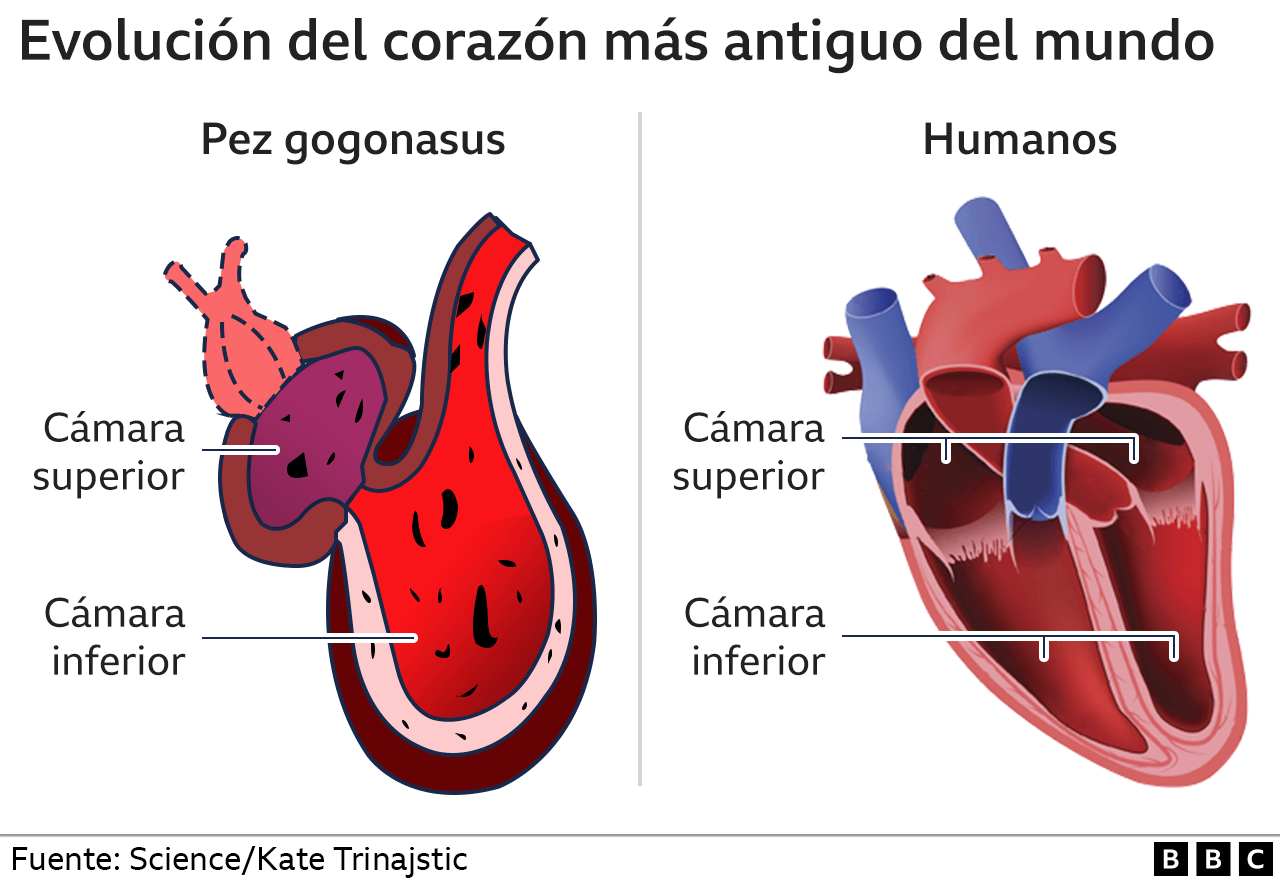

Scans of the Gogo fish fossil showed that its heart was more complex than expected for these early fish.

Similar to the human heart

It had two chambers, one above the other, similar in structure to the human heart.

The researchers suggest that this made the animal’s heart more efficient and was the critical step that transformed it from a slow fish to a fast predator.

“This was how they were able to up the ante and become a ravenous predator,” Professor Long pointed out.

Another important observation is that the heart was much further forward in the body compared to more primitive fish.

This location is believed to be linked to the development of fish necks. gogonasus and paved the way for lung development later in the evolutionary line.

“Part of our evolution”

Zerina Johanson of the Natural History Museum in London, a world leader in placoderms and independent of Professor Trinajstic’s team that made the find, also described the research as an “extremely important discovery” that helps explain why the human body is the way it is now.

“A lot of the things you see we have on our own bodies; jaws and teeth, for example,” he pointed. “We see the first appearance of the front flippers and the flippers on the back, which eventually became our arms and legs.”

“We have seen many things in these placoderms that we see today in our own evolution, such as the neck, the shape and arrangement of the heart and its position in the body“.

The discovery completes an important step in the evolution of life on Earth, according to Dr Martin Brazeau, a placoderm expert at Imperial College London, who is also independent of the Australian research team.

“It’s really exciting to see this result,” he told the BBC.

“The fish that my colleagues and I are studying are part of our evolution. This is part of the evolution of humans and other animals that live on land and the fish that live in the sea today.”

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC World. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.