March 26, 2023, 5:00 AM

March 26, 2023, 5:00 AM

They are navigators and fishermen, they live on the banks of the Ichilo River, but they must go upstream. The close to 3,000 inhabitants of the Yuracaré-Mojeño town are settled in 14 communities scattered and isolated from urban centers in a territory of 76,000 hectares in Santa Cruz. To visit them, you have to jump downstream from Puerto Villarroel, in Cochabamba, aboard boats powered by ‘teques’, small engines adapted for sailing.

In addition, as they themselves comment, the hydrocarbon subsidy does not benefit them, since they pay up to Bs 10 for each liter of gasoline, a price that doubles the price regulated in the rest of the country. “We move our ‘teques’ with fuel, but they don’t sell us the amount we need and we have to resort to the ‘black bags’ (black market),” said Néstor Vásquez, the chieftain of the Yuracaré-Mojeño, during a conversation that held with THE DUTY.

“They have told us that this is a red zone; however, no one has stopped to think that in the TCO (Community Territory of Origin) which is on the banks of the Ichilo River. The road we have is the river and, per day, our ‘teques’ can consume up to 30 liters because they travel long distances to reach scattered communities,” he said. The farthest is a day’s journey across the river.

To purchase fuel in a drum, you must present photocopies of your ID and the sale of up to five liters per person is allowed. The main supply center is precisely in Puerto Villarroel, a strategic site for this town.

Gasoline, along with other fuels, is considered a precursor for the manufacture of cocaine. The Yuracaré Mojeño territory It’s in the municipality of Yapacaní, declared by the Special Force to Fight Drug Trafficking (Felcn) as an area of illegal coca and drug production. Although the trend decreased in 2022, in the Choré reserve 200 hectares of illegal coca crops were destroyed. A part of the protected area is in the TCO.

Of course, this indigenous people has political power and has a representative in the Departmental Legislative Assembly, but MAS allies have targeted that and the rest of the indigenous seats since 2021, when the legislature began. The indigenous bench is made up of five seats that are key in the correlation of forces.

Although Creemos won the elections with more than 55%, that majority was not reflected in the Legislature because the MAS achieved support in several of the Santa Cruz regional constituencies. So, the governor’s party Luis Fernando Camacho it has 11 seats; The political organization that Morales directs from his stronghold in the Cochabamba tropics also has 11 seats. Puerto Villarroel is part of that coca-growing region.

“If the assembly members of the indigenous movement join in, we are the majority and in my experience, if we are a majority, the department can be managed from the Assembly and that is under analysis ”, stated Morales in April 2021 after knowing the results of the subnational elections of that year.

Vásquez remembered that position, but wondered about the absence of development projects during the 14 years that Morales governed. “We have been excluded for several efforts and now we feel denigrated,” the chief lamented shortly after expressing his support for Assemblyman Wilson Cortez, who has a revocation report against him endorsed by the Santa Cruz Electoral Tribunal.

The decision was appealed and was also sued in court. The ruling is expected to be issued in the course of this week.

An aerial view of the Puerto Villarroel pier from where you navigate to the Yuracaré-Mojeño territory. Photo. Jorge Ibanez

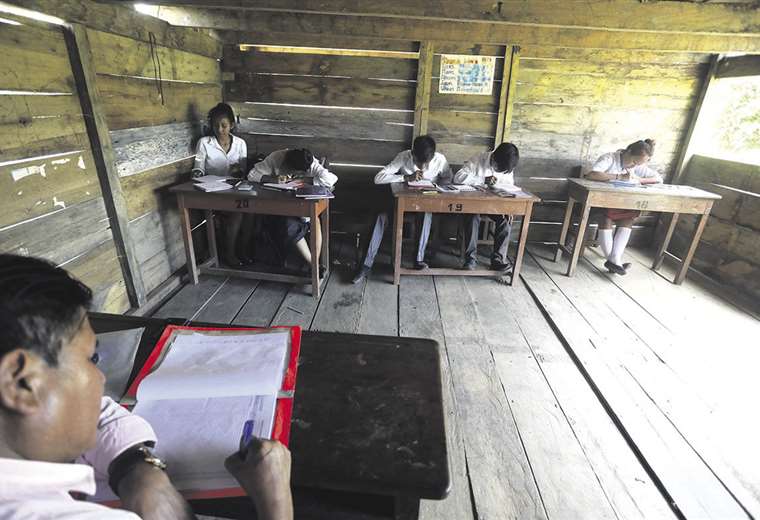

Meanwhile, there are more needs. A Yapacaní medical brigade visits the communities of this indigenous people every week. The only health post is in Pallar, what is it like the political capital of the TCO. There is a community center, a school with five teachers and 40 students. Two of them are in their last year of high school and this year they will graduate as high school graduates.

For this reason, Joel Colque and Evlyn Mole have plans. He wants to be a policeman. “We only live from fishing and the chaco; There is nothing more to do. The key is study. Without the study we are nothing”, affirmed the young man, who trusts to be able to leave their community to form.

She wants to be a nurse. “We need better health; the kids get sick often and the doctors don’t always come,” she said.

The director of the Puerto Pallar Educational Unit, Carla Torrico, explained that “there are many needs like the lack of drinking water and an appropriate signal for the Internet”. He explained that since this year they have electricity generated by solar panels installed by the Government.

The school’s teachers teach several subjects at the same time, “because there are no specialized teachers,” noted Professor Liseth Moroscopa, when EL DEBER arrived at the school.

The school’s biggest challenge is to prevent students from dropping out to meet the economic needs of their families, since the main activity is fishing and growing products such as cocoa. “The land is very fertile because of the humidity of the river,” said Assemblyman Cortez.

With that vocation, andIn the Tres Lagunas community are installed six out of 11 cages for the breeding of Tambaquí, a species that is already commercially exploited in the department of Cochabamba. To get the product to the market, you must go to Puerto Villarroel where the Cochabamba Government charges a tax of Bs 0.50 per kilo. The resources go to the neighboring department, claims the assemblyman. Coordination is required between two governorates that are under the control of two opposing sides.

He explained that they are waiting for an environmental impact study to be able to propose the highway project that links the indigenous territory with its department of Santa Cruz. “Actually, 30 kilometers are needed, because there are neighborhood routes that, administratively, depend on the municipality of Yapacaní. In fact, the Yuracaré-Mojeño indigenous territory is municipal district 15. The community also has a representative of this town in that Council.

40 students attend the precarious school in Puerto Pallar. Photo. Jorge Ibanez