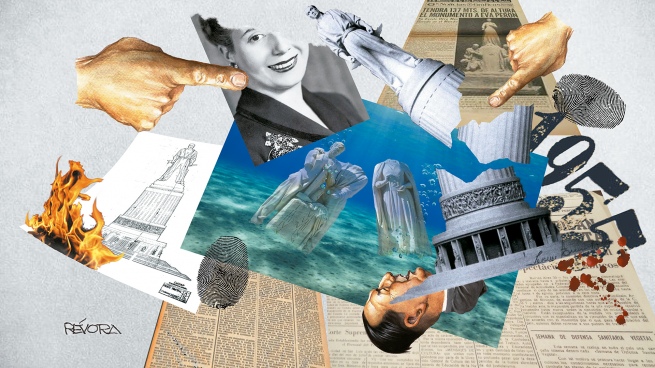

The myth lives and returns. It reincarnates in books, films, objects, photographs, testimonies, documents. Or, as in this case, it returns from under the ground itself, with the historical rescue of maps, plans and photographs that refer to known lots where constructions lie buried by the useless gag of censors. The myths that live come back. This one in particular, made a metaphor: in the image and likeness of the “subsoil of the revolted homeland” that Scalabrini Ortiz evoked.

It is not a secret: Perón and Evita sought to capture the social dimension of their political work in building, physical works that would express in concrete and cement the correlate of the transformation they had procreated. They wanted the public space to be a mirror of those multitudes rising up in a new collective construction, on a par with the rights revolution. From that conception was born “The monument to the descamisado”.

The ambitious work that today, with its myth, returns from the traces revealed by architects, historians and photographers suffered at the time a reformulation: after revealing the terminal illness of “the standard-bearer of the humble” it was decided that the monument would be the definitive home of his remains, in addition to honoring the worker.

The version that the gigantic figure of the worker – a 45-meter-high “shirtless” colossus destined to crown the top – would be replaced by one of Eva is wrong. The conversion of the monument into a mausoleum did not imply this, but precisely the incorporation of the sepulcher into the bowels of the tribute, revealing an inseparable conjugation.

On July 4, 1952, 22 days before Eva died, Congress passed Law 14,124, which provided for the erection of the “Monument to Eva Perón” memorial. As for the exterior design, the construction plans remained the same when the works began on April 30, 1955, in which Perón himself, now a widower, unloaded the inaugural spoonful of cement.

If completed, it could be the most lavish architectural public work in the world. This is evidenced by its 138 meters high, 100 meters of basal diameter, more than 30 levels, 14 elevators, a high viewpoint, 42,000 tons of cement and the underground crypt where the remains of Eva Duarte would rest inside a sarcophagus of 400 kilos of silver

“The project was and still today would be immense. Let’s think that it exceeds, for example, the tower of Pisa, the statue of Liberty or the Eiffel tower”, explains Sebastián de Zan, architect, leader of project of the Center for Documentation and Research of Public Architecture (CeDIAP), in turn dependent on the Agency for the Administration of State Assets and the Head of the Cabinet of Ministers.

“The idea of locating Eva’s coffin inside the monument is inspired by Napoleon’s tomb in the Les invalides palace in Paris. There -as here- to see the coffin, the design was made in such a way that it would be necessary to bend down and look out onto an internal balcony; a bodily gesture that implies a reverence. The circular burial chamber has a central layout with a dome-shaped roof through the center of which a beam of natural light enters.”

In turn, De Zan illustrates: “The monument was going to be located in front of the current National Library, involving an entire urban plan. Such a scale required an essential integration with the environment.”

To give us an idea of the site where construction began, De Zan points out: “According to our calculations, the photos correspond to the property where the pool is located today in one of the squares between Figueroa Alcorta and Libertador. Unfortunately, no excavations could be carried out to verify it, but everything indicates that this would be the approximate area”.

The images included in this review are part of the documentary collection of the former Ministry of Public Works that CeDIAP rescued after it was abandoned in inappropriate deposits and has been managing since 1993. Within this framework, “the Center is in charge of digital preservation of historical documents in the matter”, concludes De Zan.

Télam had, for the preparation of this report, the advice of the Ministry of Public Works, and in particular the team in charge of the Architect Carlos Rodríguez, Secretary of Public Works of the Nation, who also spoke with this medium: “I think there are to read, among other things, the place where this was located. It is an affirmation in an elite point of the City. On the other hand, it poses something counterfactual. Because, if it had been concluded, it would surely have been demolished by the ‘Liberator ‘”, he pointed.

Sociocultural irradiation does not escape Rodríguez’s analysis: “Cities are made of three levels. One is the one we see and touch. Another is the one that existed, and was demolished. A third level is that of the imagined. When you combine the three , suggestive things are represented. Here we are talking about the city that was not, the city of Peronism. I find the appearance of a monument like this interesting because it is disruptive and speaks of something that could well have been: not only as a monument project, but as a project for a city, a country”.

For his part, in relation to this case and in line with the current Program for the Reconstruction of Memory and the Strengthening of National Identity led by the ministry, he adds his testimony to Télam María Pía Vallarino, director of Institutional Relations: “The public infrastructure and architecture express country projects and the type of dialogue between the authorities and the town, its people, reflects the recognition or invisibility of the different political, social and cultural identities at a given moment”.

Vallarino emphasizes that “recovering the histories of the projects of the works, the archives and material and symbolic heritage implies valuing the collective memory. Knowing the past, we believe, serves to plan and build a better future for our society”.

“About Eva, I add that the archives show the need to bury the workers’ and Peronist struggle and the rejection of the love that the humblest working class had for Evita by the dictatorship of ’55, which unfortunately deepened with the coup of 1976. It is good to know this truth to strengthen the current democracy and improve it,” the official highlights.

Vallarino completes: “The differences should be synthesized in the vote and institutional exercise of participation and dialogue and not in the annihilation and denial of those who think differently. However, no matter how many walls, blocks or ceilings they want to erect, the feeling, admiration and Popular support for Eva’s work, to this day, is still valid and cannot be erased or disappeared”.

Towards June of 1955, the monumental construction already showed great advances. / Photos: Courtesy of CeDiap, AABE.

Other victims of the forgetful shooter

In its attempt to erase memory and history, the “shooting” revolution of 1955 proceeded, shortly after usurping power, to seal the already advanced foundations of the work. In parallel, they mutilated and threw into the Riachuelo the set of five Carrara marble sculptures commissioned and made ad hoc by the Italian Leone Tomassi, to decorate the mausoleum.

Those pieces, four and a half meters high and weighing 35 tons each (with allegorical titles such as “Economic Independence”, “El Conductor”, “El Justicialismo”, “La Razón de mi Vida” and “Los Derechos del Trabajador” ), were rescued decades later, in democracy, and distributed between the fifth October 17 in San Vicente, in Mar del Plata and other points.