We are the only animal that stumbles twice on the same stone, it is often said. Gunter Demnig (Berlin, 1947) plays with the idea and proposes that, when it comes to history, memory could save us from a second stumble.

The memory that Demnig builds with his hands is, in fact, in the shape of stone. His “Stolpersteine” (plural of “stone-obstacle”, stone in the way) are spread across Europe in tens of thousands. They are not anywhere: they mark the last resting place of someone who was sent to an extermination camp during the Nazi-fascist barbarity.

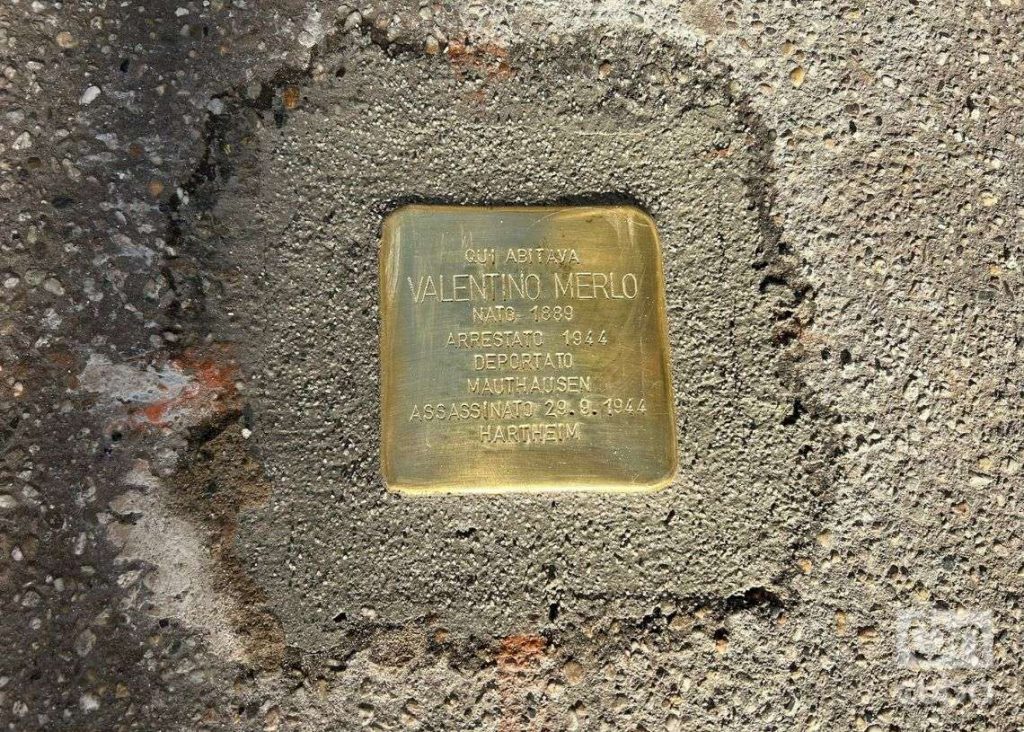

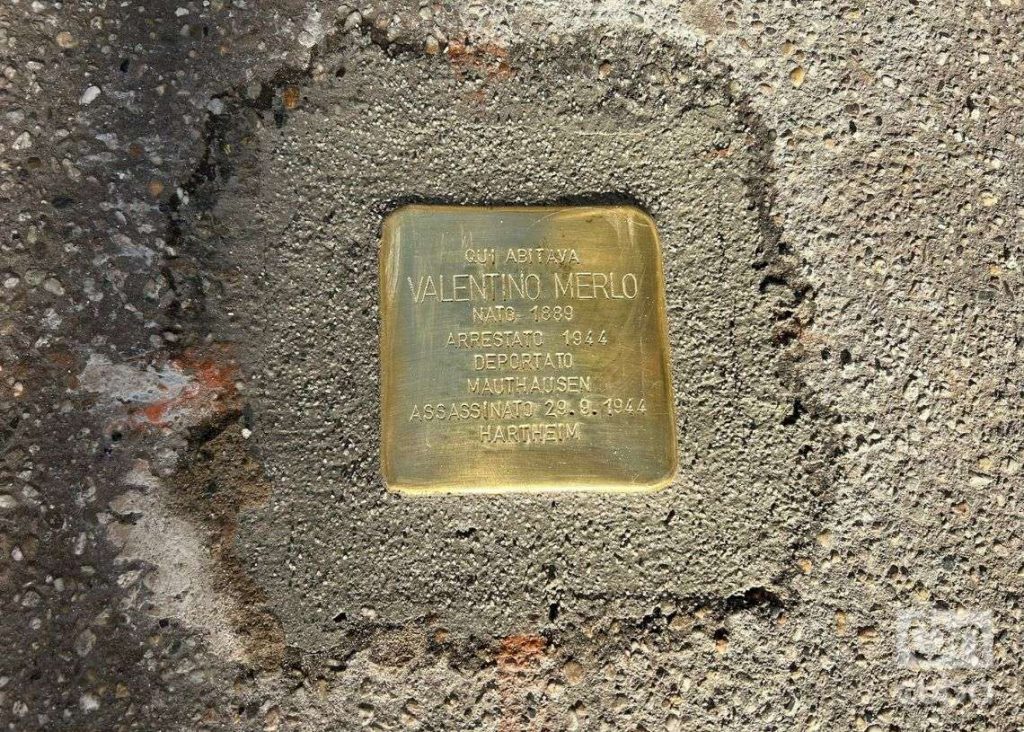

They are 10 cubic centimeter pieces topped with a plaque containing the person’s name, date of birth, date of deportation, and date of death. In some —very rare cases— it reads “survivor”. Others—not a few—are embedded in a group: it means that a family was deported. They protrude slightly from the ground, just enough to make their presence known and invite the passerby to lean down to read the message they contain, in the form of a small bow.

In Turin, northern Italy, there are so far 143 pietre d’inciampo (in Italian). The last thirteen of them have just been placed while the city hosts for the ninth consecutive year the project by the German artist, son of a soldier who served in France.

But Demnig’s motive was not family. The idea dates back to 1993, when he was sent to Cologne, Germany, to make an installation on the deportation of Roma. An old woman from the place assured that gypsies had never lived there. The artist then decided to dedicate himself to leaving testimony in space of the existence of citizens disappeared by the Nazis. He laid the first stones in 1995, right in Cologne.

“I had the idea of returning the names to their own space, to the houses in which the journey towards death began,” Demnig tells OnCuba still in Via Breglio 18, where he had just placed his most recent Stolpenstein.

Throughout almost thirty years of work, many names have passed through his hands. Names in Spanish, French, German, Hungarian, Czech. All under the sign of the same nefarious destiny. Demnig works the pieces personally and has placed almost all of them himself, on his knees. “As a symbol, I consider it important,” he explains.

The artist affirms that he is not afraid that something like the Holocaust will happen again. He assures that “young people are interested and have wanted to understand how it was possible; We will try to make it something that will never come back.”

A great scattered monument

“It is a relational art intervention that gives life to a kind of dispersed monument”, he comments to OnCuba Roberto Mastroianni, director of the Museum of the Resistance in Turin. The Museum coordinates the group made up of the National Association of Former Deportees, the Goethe Institute and the city’s Jewish Community that is carrying out the project.

“They are placed in the last place of voluntary residence of the deportee, transferred for religious, ethnic, sexual or political reasons, like the stone that we have placed now,” he adds.

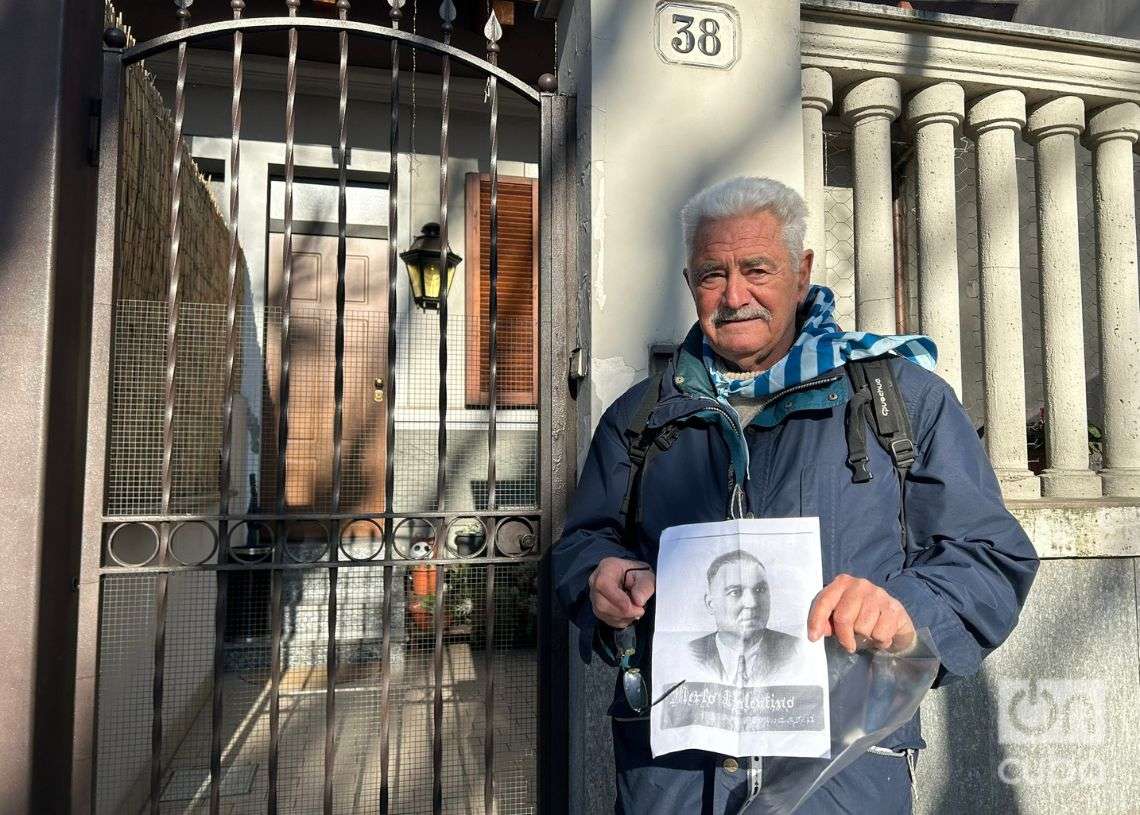

It refers to the placement in memory of Valentino Merlo, “classified as a communist” and denounced for “offending the head of the Government” for his participation in the strikes of 1943 and 1944 against the Mussolini regime. “He was a Fiat Sima worker; they deported him to Mauthausen and he died there in September 1944”, reveals Mastroianni.

“We wanted to include a common person —he explains— who lost his life as a consequence of a daily act of heroism, of resistance against barbarism; a worker with the courage to oppose the regime.”

“I found it useful to propose it”

Normally it is relatives or acquaintances who request the placement of the stone; In addition, there is a record of deportees and partisans in the State Archive and the Ministry of the Interior. The Museum receives the applications and then coordinates the fabrication and installation with Demnig.

In the case of Merlo, however, the proposal was not made by someone close, but by a professor who was the son of partisans.

“His story seemed significant to me because he was not a boy. He was a mature person who knew what he was doing and the risk he was taking. I found it useful to propose it”, says Lucio Monaco.

“The Association of Ex-Deportees was created in 1945 in Turin by and for ex-deportees; but currently it is open to all who are interested in the subject or may have met someone, ”says Monaco when explaining his membership.

“I don’t have any relatives who have been deported, but I always took my high school students to the concentration camps together with survivors who gave us their testimony. I was very attached to that experience, ”he adds.

Lucio Monaco is a teacher of Italian Language and Latin, “not of History”, he laughs, assuming that I could have assumed that he was.

coordinates in the world

Before arriving at the extermination camps and becoming meat in the horror machinery, there was a home address, a neighborhood, neighbors. They were citizens, part of a human network and environment. They crossed the door of the house every day, the threshold between the two spheres of existence that had been torn from them, the public and the intimate, private.

Before being taken to hell on Earth, far from everything known, they had coordinates in the world. Demnig stones mark them. They return the ghost home.

We walked among ghosts, we crossed the streets that crossed, under the same porticos, seeing what they saw. The stones name them, return them to the place from which in life they should never have left but of their own free will. And they bring us closer: they were —things more, things less— as we are; we are as they were. And they were not few.

In the middle of the year, in Dachau, the hundred thousandth stone will be laid. A hundred thousand chances not to stumble.