The establishment of gay marriage in the United States did not come on a bed of roses. In this long and winding process, one of the first documented cases was that of law student Richard Baker and librarian James McConnell. In 1970, a year after the riots in stonewall, the couple applied for a marriage license in Minnesota. As expected, the authorities rejected their request, because they were of the same sex. Baker and McConnell appealed, but the state Supreme Court upheld the trial judge’s decision in Baker. vs. Nelson (1971). They appealed again (1972), but the US Supreme Court refused to hear the case for “lack of a substantial federal issue.” This ruling prevented federal courts from ruling on same-sex marriage for decades, leaving the decision up to the states.

But the landscape began to show some fissures during the 1980s and 1990s. In 1989, San Francisco passed an ordinance allowing unmarried homosexual and heterosexual couples to register as domestic partners, giving them specific legal rights and other benefits. And in 1992 the same thing was passed in the District of Columbia. But in 1993 something huge happened: The Hawaii Supreme Court ruled that a ban on same-sex marriage could violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Hawaiian Constitution. (Baehr vs. Mike). It was the first time that a court of that rank endorsed legalizing same-sex marriage. Filed by a gay couple and two lesbian couples who had been denied marriage licenses, the lawsuit was ultimately dismissed. But a new precedent would be created.

The entrance to the new century would bring new developments in this area. In 2000, Vermont became the first state to legalize civil unions, a status law that provided most of the benefits of marriage at the state level. Four years later, Massachusetts struck tradition by becoming the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. If Goodridge vs. Department of Public Health, the Supreme Court of that state ruled that same-sex couples had the right to marry and therefore on May 17, 2004 the state began issuing marriage licenses for gays and lesbians. But inevitably the decision made noise with the federal norm, which went in the opposite direction. Indeed, the Defense of Marriage Law (DOMA, for its acronym in English), a federal law passed by the 104th Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton in 1996, defined marriage as the union of a man and a woman, and allowed states to refuse to recognize marriages between people of the same sex made under the laws of other states.

In 2007, a New York lesbian couple (Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer) got married in Ontario, Canada. The state of New York recognized the marriage, but the federal government did not, for the reasons already mentioned. When Spyer died in 2009, she left her estate to Windsor. Because the marriage was not federally recognized, Windsor did not qualify for tax exemption as a surviving spouse (had he been a married straight man or married straight woman there would have been no such problem). The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) then imposed $363,000 in taxes on him. But in late 2010, Windsor filed a lawsuit against the government.

In 2010 Massachusetts ruled that Section 3 of the DOMA was unconstitutional. In 2012, for the first time in history, voters in Maine, Maryland, and Washington—not their judges or their legislators—approved constitutional amendments to allow same-sex marriage.

That same year, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled that the aforementioned Section 3 of DOMA violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments in the case. United States vs. Windsor. The following year (2013), the highest court in the nation ruled in favor of the plaintiff and annulled Section 3. History was already being made.

Obergefell vs. Hodges

James Obergefell and John Arthur James filed suit challenging the state of Ohio’s refusal to recognize same-sex marriage on death certificates. The two had been legally married in Maryland in 2013. James was terminally ill, dying several months into the litigation. Because of Ohio law, the plaintiffs believed that state officials would refuse to accept that James was married at the time of his death and that Obergefell was his spouse.

They filed the case on July 19, 2013 in the Ohio Southern District Court. A judge granted a temporary restraining order requiring the state to recognize the marriage on the death certificate. On September 26, 2013, those involved filed a lawsuit adding several additional plaintiffs, a total of six, from the states of Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee, with the same or similar problems.

They argued that the practice of denying recognition of marriages legally performed in other states on death certificates was unconstitutional and sought an injunction to stop it. On December 23, 2013, a judge held that Ohio’s refusal to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states violated substantive due process and equality rights. He also declared unconstitutional the ban on recognizing same-sex marriages lawfully performed outside of Ohio.

But the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed its decision, holding to the contrary, namely that state bans on same-sex marriage and refusal to recognize marriages performed in other states did not violate 14th Amendment rights of couples to equal protection and due process.

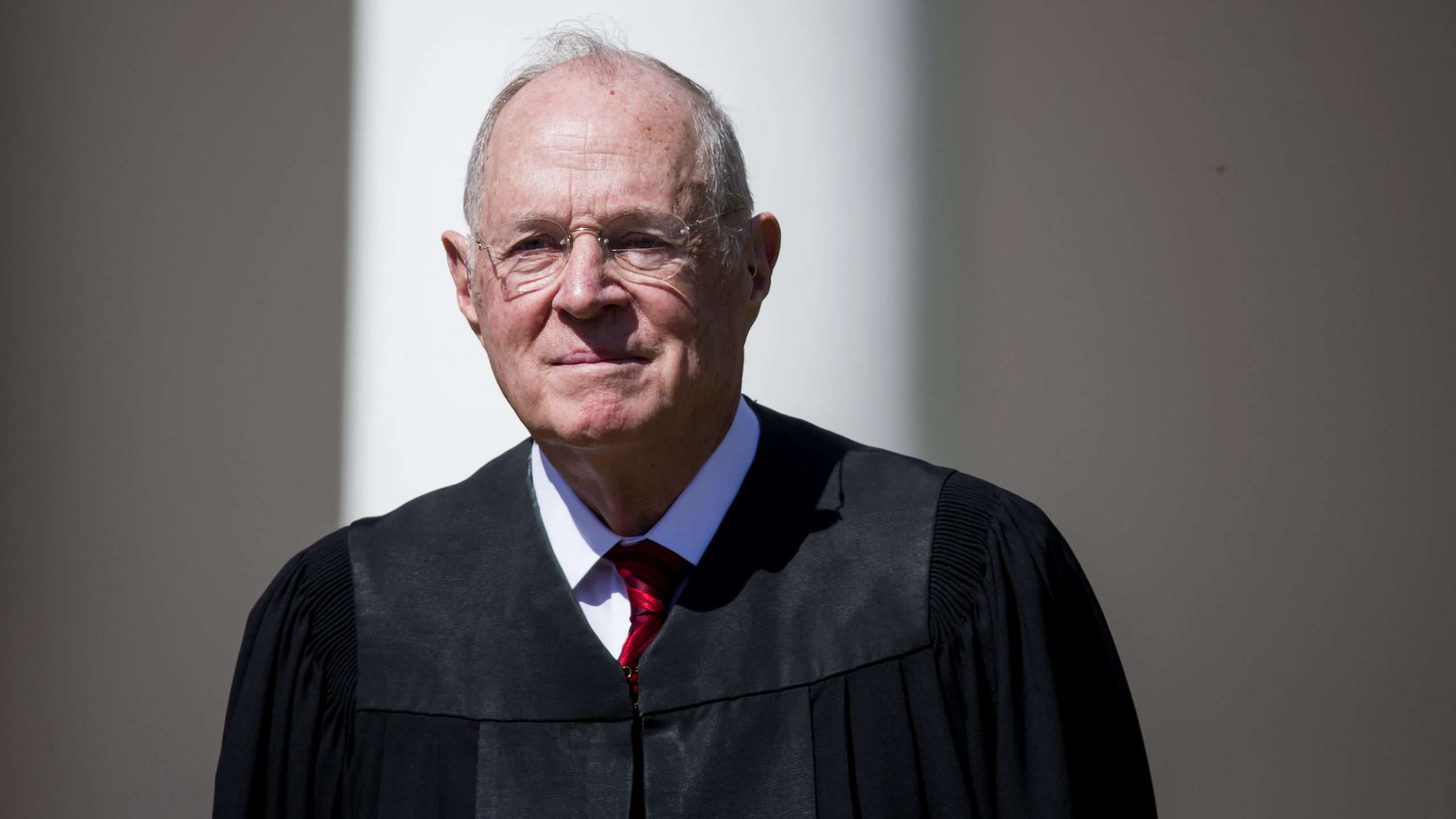

Finally, the Supreme Court entered the game. Having accepted the case, on June 26, 2015, it ruled, in a landmark decision, that the 14th Amendment required all states to authorize same-sex marriages and recognize all marriages lawfully arranged out of state. A very divisive ruling: 5-4.

Speaking for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that the right to marry was a fundamental right “inherent in the liberty of the person” and therefore protected by the due process clause, which prohibits states from depriving any person of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” Because of the close connection between liberty and equality, the right to marry was also guaranteed by the Equal Protection Clause, which forbids states to “deny to any person…equal protection under the laws.”

Kennedy argued: “the reasons why marriage is fundamental”, including its connection to individual freedom, “apply with equal force to same-sex couples”. Those considerations, he concluded, compel the Court to hold that “same-sex couples can exercise the fundamental right to marry.”

Abortion rights in the US: Roe vs. Wade, a watershed torpedoed by the Supreme Court

Not by chance, that ruling emphasized an element of the greatest importance and timeliness, valid even for other contexts: those who “adhere to religious doctrines can continue to defend” their convictions in the sense that “by divine precepts marriage between people should not be tolerated.” of the same sex”. The First Amendment allows them that right and protects them. It also protects the exercise of your religion: the decision does not require that any religion implement or recognize same-sex unions, nor that any opposite individual is obligated to personally participate in that union.

His opinion was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer (1938, recently retired from Supreme), Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933-2020), Elena Kagan (1960) and Sonia Sotomayor (1954). The main dissenting opinion was given by Chief Justice John G. Roberts (1955), the same one who fills that role today. He was joined by conservative Justices Antonin Scalia (1936-2016) and Clarence Thomas (1948), who also recorded their own votes to the contrary, as did Justice Samuel A. Alito (1950), the latter one of the singing voices at the time of annulling Roe vs. Wade.

Having achieved that, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that his colleagues should now “reconsider” other rights established by that court, including access to contraception and gay marriage. “In future cases we should reconsider all of this court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell,” he noted, referring to historical opinions that prevented states from banning contraception. [Griswold vs. Conneticut, 1965]sex between homosexuals [Lawrence vs. Texas, 2003] and gay marriage [Obergefell vs. Hodges, 2015]. “After overturning these decisions demonstrably wrong”he emphasized, “the question would remain as to whether other constitutional provisions guarantee the variety of rights that our substantive due process cases have generated.”

It will be said that he was not escorted by the rest of the conservatives; The problem is that they are too smart to announce everything they want to dismantle in one fell swoop. But, without a doubt, they are heading for that and more, strengthened by Donald Trump’s nominees and altering the balance and internal balance of the Court for a long time.