“The regret would have been not having done anything that day for the people of Venezuela,” said Víctor Hugo Morales, who today, exactly six decades ago, participated in the so-called Porteñazo, a civil-military rebellion against the government of Rómulo Betancourt. .

This 95-year-old man, at the time, was a Lieutenant Commander in the Navy. In an interview conducted on January 23 by Ernesto Villegas in his Sunday program, Morales explained some details of that uprising that, although defeated, left its mark on future revolutionary processes in our country.

“At that time there were many army, navy and infantry officers from Puerto Cabello, Carúpano, Maracay and other cities, dissatisfied with the Betancourt government, who had betrayed the democratic ideals of January 23, 1958, turning his back on the people. Morales argued.

“There was a lot of youth movement in the streets of Caracas, Mérida and other cities that showed that great discontent. In addition, the Cuban Revolution was a beacon of inspiration,” Morales recalled.

Soldiers and militants of the PCV and the MIR had been fighting since 1960. In 1962, practically a month before (May 4), the Carupanazo uprising took place (by the naval base located in Carúpano, Sucre), defeated at the time.

However, that first coup attempt set the stage for the second to happen soon.

At dawn on Saturday, June 2, 1962, there was an uprising at the naval base of Puerto Cabello, Carabobo state, led by the ship’s captain Manuel Ponte Rodríguez, the frigate captain Pedro Medina Silva and the lieutenant commander Víctor Hugh Morales.

They mobilized and occupied various strategic sites in the city, such as the Parque de la Base, the Castillo Libertador (where they freed and armed dozens of guerrillas and part of Carúpano’s insubordinate non-commissioned officers), dominated Fortín Solano, seized the Cuartel de la Digepol and that of the municipal police, subsequently submitting the prefecture.

Despite the rapid deployment, the rebels did not have the National Guard detachment that was at the Puerto Cabello pier, which was supposed to block the highway between Valencia and Barquisimeto, to delay the entry of forces loyal to Betancourt.

But it was not like that. In addition, they did not count on the fact that the squadron did not allow any of the ships to be taken, managing to anchor outside the roadstead and activate their artillery in support of the government, which their loyal forces soon sent, causing strong air and land combat during that day. . The bloodiest were in the La Alcantarilla sector.

Finally, on Sunday, June 3, the Ministry of Internal Affairs announced that since dawn the Armed Forces loyal to the government had put an end to the rebellion, although it was only three days later that the last group of insurgents in Fortín Solano surrendered. This uprising left a sad balance of more than 400 dead and 700 wounded.

Of course, unlike the Carupanazo, the Porteñazo represented a civic-military conspiracy of greater magnitude, both due to the forces involved and the intensity of the struggle.

“The population, gosh, the way they behaved that day was admirable,” concluded Víctor Hugo Morales.

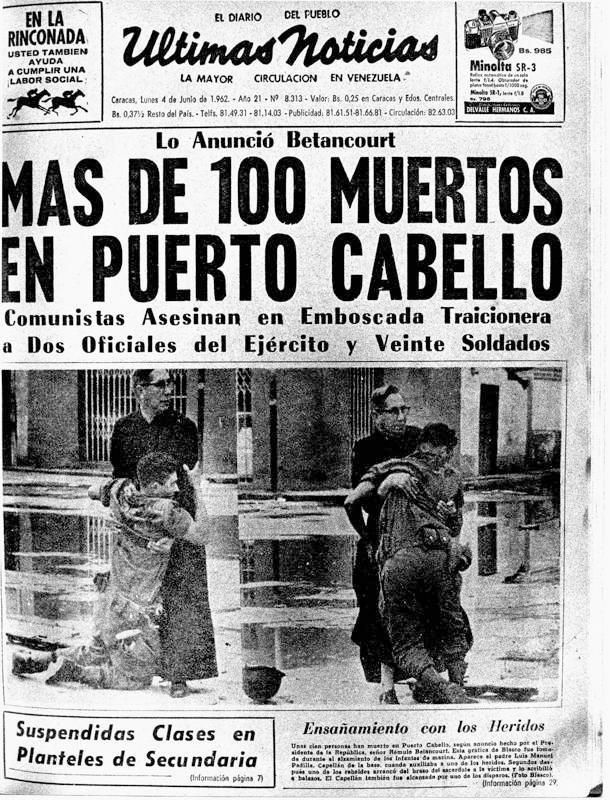

Pulitzer 1963

There were several photojournalists who, avoiding the equal lead of both sides in the dispute, made an effort to take the best photos to show the bloodiness of that coup in Puerto Cabello.

One of them is Héctor Rondón Lovera, who worked at La República. Together with José Luis Blasco, for Elite, they arrived at the La Alcantarilla sector, where the highest number of deaths and injuries were recorded.

That is where Rondón observed the priest Luis María Padilla, chaplain of the Puerto Cabello naval base and parish priest of Borburata, helping the wounded, especially a soldier who he lifted, but died in his arms.

Rondón recounted on several occasions: “the priest in front of us began to check the wounded. One in the middle of the street raised his head.

The priest tried to help him. He picked it up. He tried to carry it. I took the photo with my Leica.” A graphic that led him to win the Word Press Photo (1962) and Pulitzer Prizes (1963).