Christian Nielsen

Works and writers that took me by the hand to the world of reading.

I am going to allow myself, with the permission of the kind reader, as the Victorian writers used to say, to recount my first experiences with reading.

My uncle Ramón, of proud Basque lineage, had an encyclopedia on his desk entitled El Tesoro de la Juventud that I first had to limit myself to browsing (from a distance) and that I only managed to browse when I was 9 years old. I was especially fascinated by his prints. Published in 1915, all the advances and technical novelties were typical products of the second industrial revolution, a world full of levers and steam engines.

At the age of 10, three books fell into my hands in a special edition for young people: Tales from the Alhambra, by Washington Irving, Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe and The Last of the Mohicans, by J. Fenimore Cooper. My older cousin was the one who saw to it that my reading was appropriate for my age. But I was cheating. He had other readings that escaped the rigid family censorship.

CLANDESTINE MARKET

The stories of the little Indian and the lonely man on the island could be very edifying, but I wanted something more. So I entered the clandestine reading market made up of other subjects of my age and appearance.

I became fond of cowboy novels. At that time, the Six Shooter and Bison collections were in fashion, with characters like Roy “Cleaning” Evans, a gunslinger who, with his Colt 45 Peacemaker, could take down the bad guys in a town before having lunch. Marcial Lafuente Estefanía was my favorite author, even when he wrote under the pseudonyms of Tony Spring, Arizona, Dan Lewis or Dan Luce. These readings were combined with frequent forays into magazines such as El Tony, D’Artagnan and Intervalo, with comic strips and characters of all kinds.

Of course, hot magazines weren’t lacking either. Those did circulate in the most closed secrecy under the risk of harsh reprisals. Of course, the most daring episode of “Fresh Head” would be a children’s story if we were to compare it with some television programs today.

CLICK AT 13

One day The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain, came to me as a birthday present, which was soon complemented by A Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, by the same author, whose agile, mocking and wildly imaginative style immediately grabbed me.

But then there was a click in my reader itinerary. It was with Erich María Remarque’s novel Sin Novedades en el Frente, an autobiographical account of his life in the trenches of the First World War. The rawness of the images that emerged from a stark story took me to another world, as cruel as it was inexplicable. Something similar would happen to me later with Germinal, by Emile Zolá, which describes the world of coal miners in the French region of Valenciennes during the Second Empire. It was a miserable existence in deep coal seams, some half a mile deep where a firedamp explosion or flash flood could pulverize or drown hundreds of people.

But this brutal realism was compensated by authors such as Alejandro Dumas, Miguel Zévaco, Emilio Salgari and Jules Verne himself.

Dumas wrote at a breakneck pace. He left more than 1,200 works. His biographers say that his novels are more historical than history itself. In Twenty Years Later, the sequel to The Three Musketeers, he recounts in great detail the execution of King Charles I, sentenced to death by Oliver Cromwell, and his Puritan dictatorship. The literary description of the monarch is so punctilious that it could only be compared to the characterization that the great Alec Guinness would make in the film Cromwell in the 1970s, along with another great English filmmaker, Richard Harris.

THE HEAVYWEIGHTS

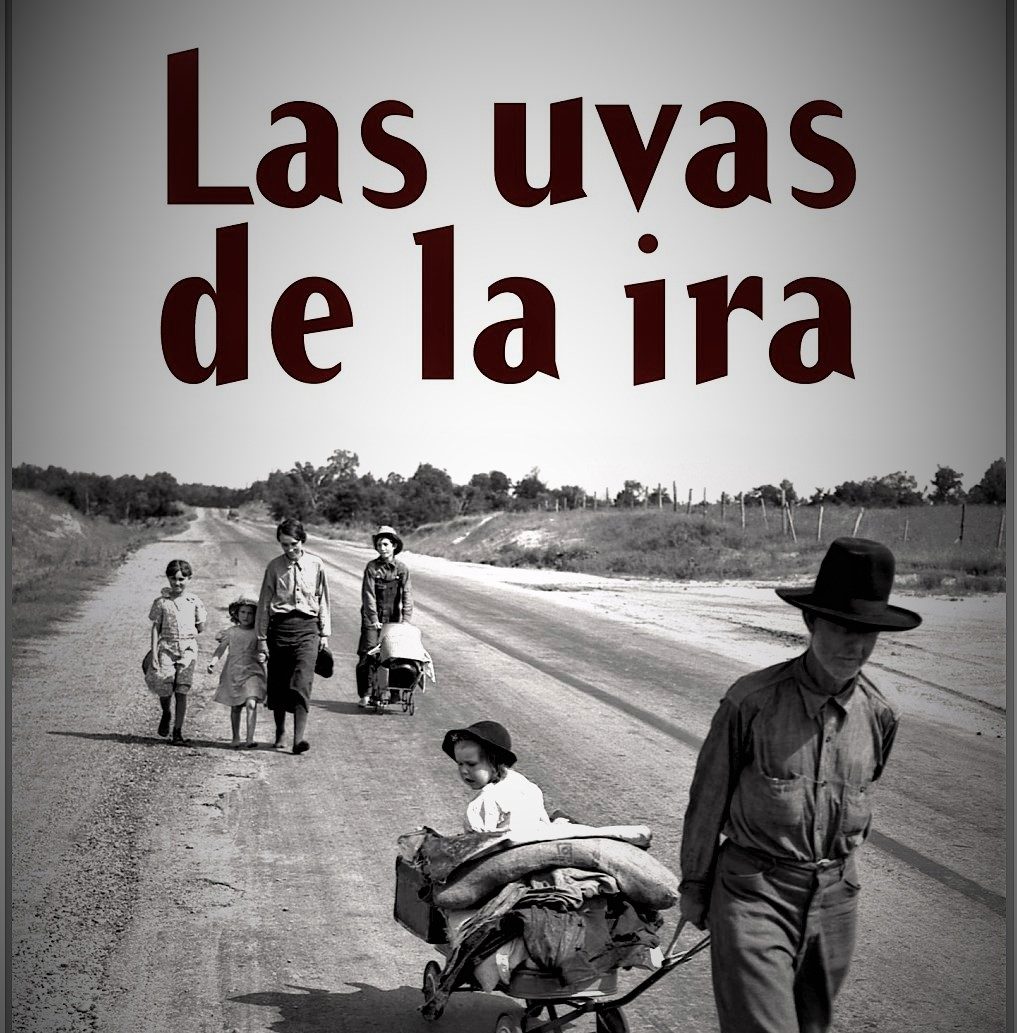

It was very difficult for me to stop reading The Grapes of Wrath, by John Steinbeck, once I attacked the first of the two volumes of the work, a masterly fresco of the Great Depression of the 1930s in the United States and the emigration of the “okies” – impoverished farmers from Oklahoma – to California. Tom Joad, the protagonist, plays the firstborn of a typical rural family who loses everything and embarks on an odyssey peppered with adventure, tragedy and hope, all at the same time. Simultaneously I coped with Horacio Quiroga’s stories, among which El Almohadón de Plumas breaks the record for horrifying stories.

My first contact with Paraguayan literature came from the hand of Augusto Roa Bastos with El Trueno Entre las Hojas and his somewhat embezzled stories in the film of the same name. Gabriel Casaccia invited me to immerse myself in his tortured universe with La Babosa y el Guajhú.

But it was José María Rivarola Matto who filled my soul with El Fin de Chipí González, a magnificent play, today translated into English and French. Rivarola was as rigorous as buzzard. Once he was asked what literary genre he preferred, given his experience as a novelist, short story writer, playwright and essayist, to which he answered without hesitation: “The requested one. Much to say, little space and very expensive”. Typical response of a word genius.

Geniuses, it is worth adding, who lead one by the hand through life.