▲ Tour of the Valente García Melchor farm in the town of Limones. Family plantation dedicated to specialty arabica coffee.Photo Pablo Ramos

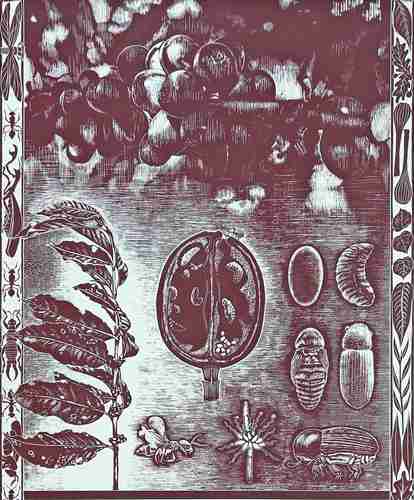

▲ Engraving by Carlos Morfín about the history and production of coffee.

Dora Villanueva

sent

Newspaper La Jornada

Tuesday December 13, 2022, p. 4

Coatepec. Migration from the main coffee-producing states of the country –Chiapas, Veracruz, Puebla and Oaxaca– increased 18.9 percent in the last decade and 40 percent compared to the beginning of the century; the four states maintain a negative balance in resident flows, according to the counts of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Inegi).

That average is exceeded when we focus on the situation in Chiapas, the largest coffee producer in the country, where emigration flows have doubled in two decades, with a rebound of 101.8 percent; Veracruz follows, with 47.4 percent. These are the states, together with Oaxaca, that in that order lead the migration of their inhabitants in search of work, show the population censuses.

The abandonment of the countryside by a generational replacement is clear among its inhabitants. I hardly see people my age here at the ranch. We are few. With the drop in price (of coffee), what many people did was emigrate

explains Valente García, a producer in Limones, in Cosautlán, Veracruz.

The hustle and bustle of some peasants backs up his words, most of those who pass by – their house is on the edge of the street layout and the farms are ahead – have thin-skinned faces and curved shoulders. Among them stands one who, like Valente, is out of tune. He is pulling his mule loaded with sacks, he prefers not to talk.

The young workforce has been lost due to poor teaching since childhood in schools

, considers the 32-year-old producer. “I listened to a classmate from Ixhuatlán at the café: ‘When I went to school they told me: learn, child, learn, learn! Or do you want to be just as stupid as your father?’”, says García.

Regardless of the boldness/condescension towards peasants promoted through educational models, García believes that the countryside will be repopulated by food crises. We all live in the countryside. Those of the countryside and the city, what would we eat?

he wonders.

Regarding a change in the care of his lands, Javier Ramos, from Acatepec, in Guerrero, comes out: What are my children going to do when they come back here? They already left my old lady and me alone

. He says that, with the exception of her youngest daughter, all of them migrated, if not to a nearby town, then to Toluca, Monterrey or the United States, but no one seems to want to return.

They know what the countryside is, suddenly those who are still here take a look at us. There in the United there are four, not three, I have three, and they tell me that they are doing well. What are they going to come back here to chaponear

he adds between laughs. But us, my old lady and I, where are we going? We don’t even want to, so what for?

Among the reasons that some producers refer to remain in the field growing coffee under biodiverse shade, despite the minor –sometimes null– economic incentives, is take root

, stand firm

on the land they received as an inheritance and included in it the habit of cultivating the aromatic.

The houses of many small producers are side by side with that of their parents, sisters, brothers, who also make coffee or sell fruit or other vegetation, such as ornamental plants, especially orchids.

Most of my land was inherited from my dad.

comments Marcos Palestina, from San Miguel Tlapéxcatl, who says that when the rust hit and his farm collapsed, the need to raise it also became a challenge to leave arable land to his grandchildren.

Regarding the incentive to continue in a crop with such uncertain prices, Darío Cadena Alarcón, producer of Naolinco, considers that is the rooting This comes by inheritance already from several generations. Our grandparents or great grandparents, parents

.

And continues: With coffee we have had years in which we are in a crisis that went flat on the ground, but there have been times when it has risen

.

Researcher Jan Ros, from the University of Sciences and Arts of Chiapas, documented that in the mid-20s of the last century, around twenty thousand indigenous people from Los Altos de Chiapas went to Soconusco and other regions at the pinch of coffee. Years later, that workforce was replaced by workers who came from Guatemala. Migration now has new characteristics: from Central America and various coffee-producing regions in Mexico, peasants leave to seek employment in other regions or in the United States.

As Luis Hernández wrote, in Migration and coffee in Mexico and Central America

:

Ironically, coffee is a product in which Mexican farmers should be profitable according to the theory of comparative advantages. But instead of prosperity and well-being, their sowing in the current conditions has condemned them to poverty, exile, death or begging. Others, on the other hand, large companies and investment funds, meanwhile accumulate more and more wealth

( https://bit.ly/3FjWz0R ).