When a factory wants to dispose of toxic waste, it charges a negative price for it: its managers pay someone to dispose of it. But when central banks start treating money like carmakers treat spent sulfuric acid, you know something is rotten in the realm of financialized capitalism.

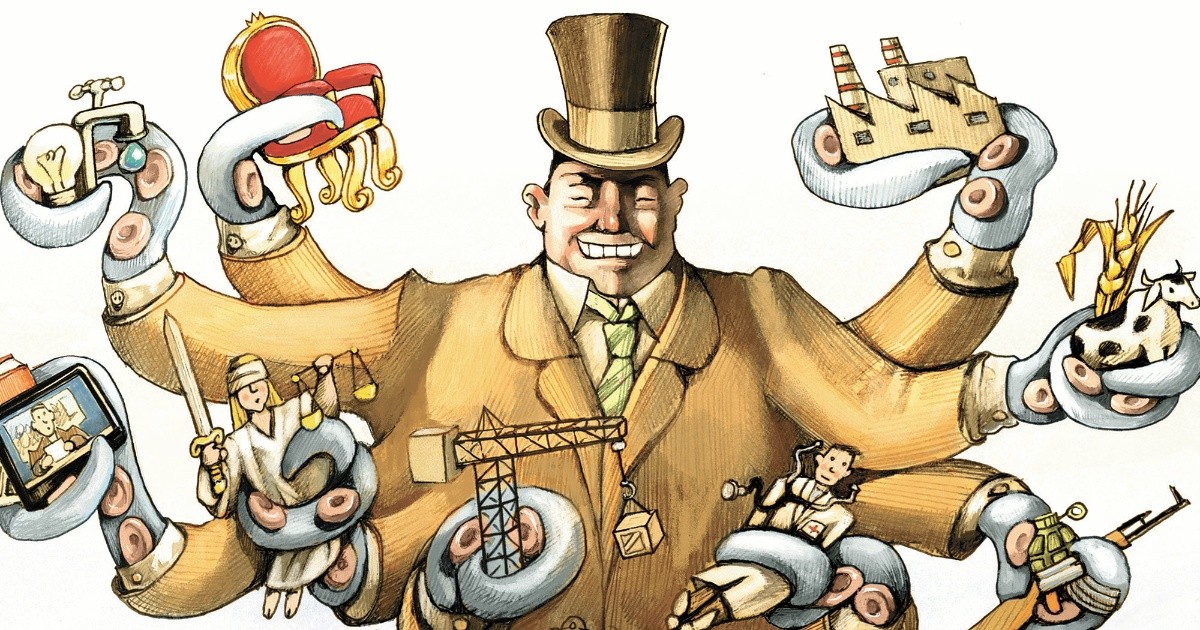

ATHENS – Capitalism conquered the world by converting almost everything that had value, but no price, into basic products. He thus drove a sharp wedge between values and prices…and did the same with money. The exchange value of money has always reflected the willingness of people to give up valuable things in exchange for it. But with capitalism, and once Christianity accepted the idea of charging for loans, money also acquired a market price: the interest rate, or the price of lending a stack of cash for a certain amount of time.

After the financial crash of 2008 – and especially during the pandemic – a strange thing happened: money maintained its exchange value (which inflation reduces), but its price collapsed and became negative on many occasions. Politicians and central bank officials had inadvertently poisoned the “alienated capacity of mankind” (Carl Marx’s poetic definition of money). The poison they administered was the post-2008 policy, in Europe and the United States, of harsh austerity for the majority, to finance socialism for the few.

Austerity reduced public spending precisely when private spending was foundering, accelerating the decline in total spending – which, by definition, is national income. Under capitalism only big business can take the big loans that lenders – mostly rich people with lots of savings – are willing to offer. That is why the price of money plummeted after 2008: its demand dried up because large companies canceled investments due to the catastrophic effects of austerity on demand, even when the money supply (for them) was growing strongly.

Like stockpiled potatoes that no one wants to buy at the going price, the price of money – the rate of interest – falls when its demand falls short of the amount available for lending. But there is a fundamental difference here: although the rapid fall in the price of potatoes quickly solves the problem of excess supply, the opposite happens with money. Instead of rejoicing at the possibility of taking cheaper loans, investors think: “The Central Bank must consider that things are bad if it lets interest rates fall so low. We will not invest even if they give us the money for free”. Investments did not recover even after central banks sharply lowered the official price of money, which continued to fall into negative territory.

It was a strange situation. Negative prices make sense for bads, not goods. When a factory tries to eliminate toxic waste, it charges a negative price for it: those who run it pay someone else to do it. But when central banks start treating money like automakers to sulfuric acid, or nuclear power stations to radioactive wastewater, we realize that something is rotten in the realm of financialized capitalism.

Some analysts now expect Western money to be purified in the flames of inflation and interest rate hikes, but inflation will not expel the poison from the Western monetary system. After more than a decade of addiction to poisoned money, no obvious method for detoxification emerged. Today’s inflation is very different from what the West faced in the 1970s and early 1980s. This time it threatens labor, capital and governments in ways it was incapable of 50 years ago. Back then, work was organized enough to demand pay raises and avoid a cost-of-living crisis, and neither states nor private companies depended on free money to get by. Today there is no optimal interest rate to bring money supply and demand back into equilibrium that will not unleash a gigantic wave of private and public bankruptcies. That is the long-term price of poisoned money.

The US government faces the impossible dilemma between limiting domestic inflation and forcing US corporations and many friendly governments into a solvency crisis that will threaten US stability itself. Things are much worse in the euro zone, where policymakers refused to implement the obvious when European banks collapsed after 2008: establish the proper basis for federation: a fiscal union. Instead they allowed the European Central Bank to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. Only by poisoning its own currency could the European Central Bank (ECB) keep the euro show afloat. The ECB currently holds huge amounts of Italian, Spanish, French and even Greek debt that it can no longer justify as a means of reaching its inflation target, but which it cannot give up without questioning the existence of the euro.

As we ponder the unsolvable conundrum facing Europe and the United States, perhaps now is a good time to think about the deeper reason money can be poisoned (which is not the same thing as debased by inflation). A good starting point is an idea that we can borrow from Albert Einstein: we can only understand light if we accept that it has two different behaviors, that of particles and that of waves.

Money also has a dual nature. The first is that of a basic product that we exchange for others, that can never explain why money can have a negative price. But the second, yes. Money, like language, is a reflection of our interrelationships and technologies. It reflects the way we transform matter and shape the world around us. It quantifies our “alienated capacity” to act collectively. When we recognize the second nature of money, everything begins to make much more sense.

Socialism for the bankers and austerity for most others stifled capitalist dynamism and left it in a state of golden stagnation. Poisoned money poured in, but not into serious investments, good jobs, or anything capable of reviving the vanished capitalist animal spirit. And now that the specter of inflation haunts us, no monetary policy can purify it, restore balance or direct investments where humanity needs them.

The author

Yanis Varoufakis, former Minister of Finance of Greece, is the leader of the MeRA25 party and Professor of Economics at the University of Athens.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 1995 – 2022