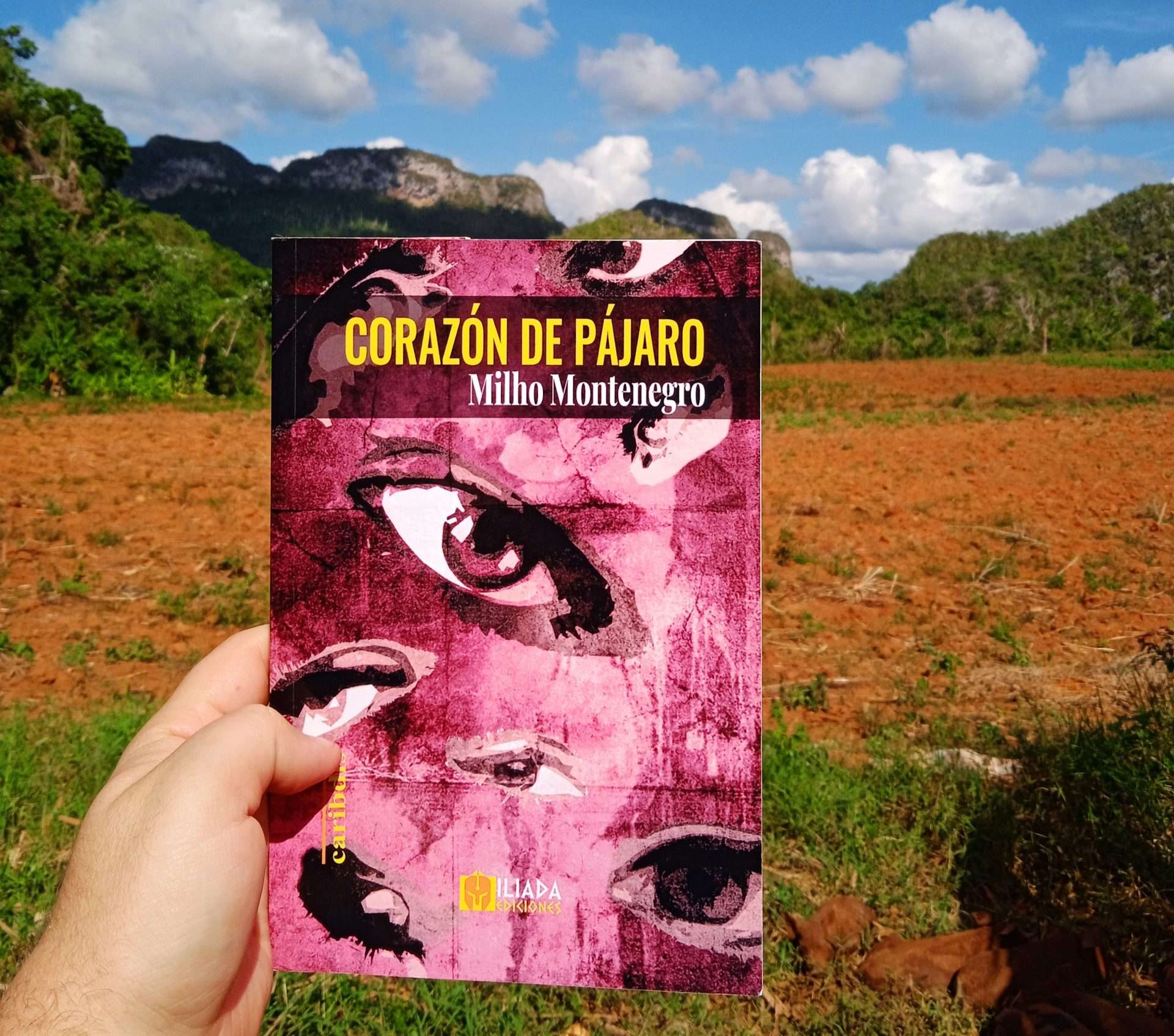

This is a short novel, winner of one of the Can Serrat Creative Writing Scholarships in Spain (2021). Its author, Milho Montenegro, has already published several books of poetry. In this, his second novel, poetry is placed very accurately.

my edit of bird heart it’s full of marks, because I’ve underlined and annotated like crazy. The story introduces us to all the characters, including the protagonist, with names that are actually just letters: A, B, F, G; except Marcos, who acquires a differentiated role from his first appearance.

The title refers us directly to the homosexual theme, if we take into account that in Cuba the man gay It is called “bird”. It seems the name of a bolero, more like a filinbecause the shape and rhythm of this story are pure filin: it has sex, feeling, rage, betrayal, revenge, and a particular voice, the result of the study of great masters of literature, and, why not? dirty the nickname

The novel introduces us to a protagonist who works at the National Library, and has a poet best friend, gayphosphorescent, talented and renegade by the political circles that dominate everything, even the world of art. After the censorship of a poetic complication, his life enters a loop of misery and paranoia that force him to make drastic decisions. Our protagonist also sees how some other co-worker is morally lynched —I must admit that this character working in the National Library reminded me of Reinaldo Arenas in his Before Night Falls, and I think it was done on purpose: it is a tribute that is introduced from the quote that opens the first chapter, taken from Celestino before dawn, Arenas’ first novel.

In the story, the narrator-protagonist’s romantic interest is called A, a psychologist who treated him for his addiction to pornography, with whom he began a relationship that ended because of emigration. The life of this man, who often describes his own heart as small and fragile, like that of a bird, will change completely when he meets Marcos, a dissident and somewhat cheeky medical student.

I recently commented with a friend that in Cuba all families are broken, and in reading this text I have found one of the reasons —because there are many— for such a phenomenon: “(…) In this country it is obligatory to carry the shit of others. Of all. That’s why many leave. The weight is too much. The crap. It is something that ends up leaving traces inside you. Shit takes root in your spirit. I don’t know if it’s actually possible to escape from that. If wherever you go you manage to cleanse your soul (…) Those who leave leave something of their own in those who say goodbye. A portion of those who remain leave with those who leave. No one is saved. No one is complete…”.

The novel touches several edges, although it does not always deepen them; leaves them at the mercy of the reader, as a task: “(…) Around the black and Yoruba there are abysses. Pending accounts. Questions to clarify. silences. Shackles still dragging…”.

It also debates about homosexuality and its condition of social and even political dissidence, about stigmas, and pays tribute to those great Cuban writers who suffered censorship and mistreatment: Virgilio Piñera, Lezama Lima, Reinaldo Arenas, Severo Sarduy, among others. He condemns the “Grey Quinquenio” and the Military Production Support Units (UMAP), that great political error that still comes to us, recounted in the form of art, by those who suffered it. And here’s my reflection: if you don’t want to look bad forever, don’t mess with the artists, the way in which the story will be told depends to a large extent on them, since politics varies a lot, but art, despite its idioms, has a testimonial edge and, against that, no propaganda campaign has ever been able. Of course! There are always dead fish that get carried away by the currents, and as Milho Montenegro says in his novel: “(…) In this country, history constantly repeats itself. And again. Like a sick cycle…”.

Here is another novel that supports my theory that the real villain of modern stories is politics, since she is the puppeteer of the characters, who then go and do things to each other to the extent that they support or oppose a certain law. Here is another novel about the Cuban reality, saving that at some point there is talk of a war that we are not aware of as such, but that exists, be careful! It exists, otherwise, they would not have attacked the people as we have already seen on several occasions, no matter how many masks they put on the matter:

“The truth does not matter to anyone in this country. The truth is a dead butterfly. An extinct species. Here everyone lies. We have been taught to lie from the beginning. Since our birth. If you do not incorporate the lie into your system then you are forced to distort the truth. To qualify it We have learned to tell lies that seem true. We repeat it so much that it is difficult for us to distinguish between one thing and the other. Between good and bad. When you tell a true truth they blame you as a traitor. of apostate. Of envious. A truth that threatens your own. Something surreal (…) If you ever find an authentic truth, keep it deep inside you. The truth should not be shared. It cannot be exposed. Unless you’re willing to die for it…”

History plays with “dissidents”, as I already said: homosexuality, pornography —prohibited in Cuba—, censored authors, sincere people, clandestine actions, and one that will arrive in a shocking way —and very realistic!—: the betrayal of humanism supported by the political game and celebrated with applause. I can’t count more without falling into a spoilers.

Another topic that touches bird heartand how bookstagrammer, voracious reader, buyer and persecutor of books I can vouch for its veracity, it is the purchase and resale of used books. In Havana, the city where I live and for which I can speak, there are second-hand bookstores, large suppliers of hard-to-find, out-of-print and uncensored editions. Bookstores that have expanded their promotion channels to social networks and messaging applications such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Facebook and Instagram, which also support the creation and dissemination of talent from their humble positions in the guild. Our author puts his protagonist to resell used books, and although the penalty he receives for carrying out this work seems exaggerated, it is true that absurdities like this happen daily on our island. In any case, these bookstores are the best suppliers of literature in the country, since they offer editions of Anagrama, Alfaguara, Tusquets, Grijalbo, Plaza and Janés, Seix Barral and other large publishers that it would be impossible for us to obtain in Cuba through the traditional channels of literary trade, not to mention authors and titles complicated:

“(…) I have several book orders. Of those that are no longer seen. Books that some consider ‘jewels’. Every day the orders increase. I am surprised by the movement of the black market of literature in this country. This is the country of eternal bureaucratism. Of the eternal barriers and walls. The country of ‘no’. That’s why almost everything here has to be behind the curtain. Covert. Secretly. I earn quite a lot. More than what I expected. Most of the customers are young. Journalism students. Of Philology. Some also tell me that they are Essayists. poets. Narrators. Others dream of being. They are amazed at my knowledge. ‘Are you a writer?’, they ask me. I rarely tell them the truth. I’m a little ashamed to be a writer with two published novels and living from a business like this. They ask for books already lost. Forgotten. prohibited. Dangerous. Books by Reinaldo Arenas. By Severo Sarduy. By Guillermo Cabrera Infante. By Heberto Padilla. I get them. I buy them at one price and then sell them for a little more expensive. Or trade them. I give this and they give me that. All clean. Fast. Easy. But behind the facade. I hang out with clients and they always come back. A satisfied customer is money in your pocket. Now I earn more than in the National Library. I am convinced that leaving was the best…”.

This snippet says it all. This is how this server gets the books from him. Once they asked me right here how he did it, in a comment.

Another detail to note are the points where some commas could go perfectly. This leisurely way of narrating is, in my opinion, a declaration of intentionality, of something well established, fixed, sure, hence what is said is enclosed between points, those that close the ideas. They mark a sharper rhythm, like the tuning fork that tunes the work that, as I already said, goes to the rhythm of filin -I think-.

The chapters are short, some very short, which helps to read quickly.

All the characters are well nuanced, there are no good-good or bad-bad, no purpose bruised by the weight of reality, no loving intention cleansed of ego. The way in which the main character transforms, evolves —regresses, it should be said— is a demonstration of the way in which the machine grinds us within dictatorships, which make you feel guilty even for calling them by their name. At times it seems that we are reading a dystopia, but it is a fictional novel, no matter how realistic it may be, a fiction that drinks from facts, people and works that are proof of a great mistake:

“(…) Of everything we ever wanted, we only had misery. Destruction. Hunger. Treason. Hatred. And promises. Absurd and pompous promises of a better future.”

This is, after all, a novel about betrayal. It uses the heart of a bird: fragile and dreamy at first, which then opens its claws and traps you in an infamous journey of loss, breakage, disloyalty, exposure. It is not for nothing that its last chapter is titled like this: “Treason”, preceded by the “Exhaustion”the “Resignation”the “Paranoia…” Not for nothing, more or less in the middle of the book, an obstinate character exclaims: “(…) History, despite being distorted, hidden or denied, will be the same in the soul of the one who betrays it…”.

I leave it there.

I thank Milho Montenegro for expressing the truth of so many and in such a courageous way, taking into account the context. Thanks for the “Librazo”, which I finished reading on a quiet afternoon in Viñales, among the sound of birds. I would have liked to hear or see a tocororo, our national bird, ideal for talking and thinking about freedom, but well, we already know that life is not usually very ideal.

Until next week.