“Artist and dreamer, given to those readings that stimulate illusion to the point of dalliance, but that do not instruct reason and feeling for the struggle for life; and left to the impulses of a certain energetic and disdainful independence, she had come to believe that the circle fixed on the young women of her time was too narrow, and the scruples of customs and the impositions of fashion no less ridiculous”.

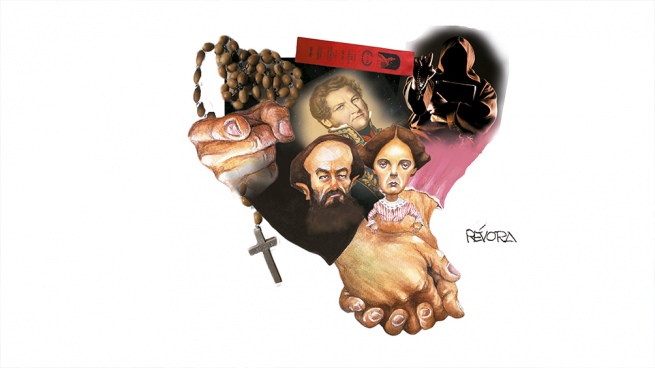

This is how Camila O’Gorman is described in the “History of the Argentine Confederation”, written in 1951 by the historian Adolfo Saldías. For Uladislao Gutiérrez there are too many lines, almost an excess of characters. He was enough to say that he was a priest, celibate, pious. Everything else didn’t matter. Or, at least, it shouldn’t matter when God was involved.

It didn’t matter what Camila and Uladislao met at one of the gatherings organized in 1843 by the aristocratic O’Gorman family at the house on Temple Street. Nor did he say that he had been a classmate in the seminary of one of Camila’s brothers and that he was also the priest of the Iglesia del Socorro (an area of farmhouses in what is now Juncal and Suipacha). Much less that the devout family attended (and confessed his sins).

Camilia and Uladislao fell in love. The secret meetings were followed by the escape on horseback during the early hours of December 12, 1847. They intended to reach Rio de Janeiro. They finally settled in Goya, Corrientes.

She was a beautiful 18 year old who played the piano, sang and felt uncomfortable in the corset of appearances that her class imposed on her and with the hypocrisy that a good part of the society of her time lived. He was a 22-year-old boy, also in a good position and he had arrived in Buenos Aires carrying letters of recommendation from his uncle, Celedonio Gutierrez, governor of Tucumán.

It will be part of literature, myth or cinema (the remembered “Camila”, by María Luisa Bembergbecame a classic of the 80s and was nominated for an Oscar in 1985) if love was born between furtive glances during gatherings or in the whispering of the Socorro parish confessional.

The truth is that Camilia and Uladislao fell in love. The secret meetings were followed by the flight on horseback during the early hours of December 12, 1847. They were looking for a new life where love was possible. But for that he had to avoid punishment. Somehow born again.

a simple plan

since that morning he would be called Máximo Brandier and she Valentina Desan. And they would live in Rio de Janeiro, capital of the Empire of Brazil, where they would be happy. No one would know of his sinful past. For that they rode a horse and They set an itinerary: Luján, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, Corrientes, Misiones and, finally, Brazil.

But the money was enough for himgo to Goya, in the province of Corrientes. They founded the first school in the town there. In your own home. “They gave affection, shelter and everything they knew to the dozens of gurises in the area. So much was the demand that they had to move twice to bigger houses to house more students”, account Philip Pigna in “Women had to be”.

But On June 16, 1848, what Camila and Uladislao could not imagine happened. They were invited to the birthday party of the Justice of the Peace, Esteban Perichon. And there was the Irish priest Miguel Gannon, who quickly learned that Máximo was Gutiérrez and that Valentina was Camila. He did not hesitate to denounce him in court.

They were arrested and, of course, separated. Three days later shackled and sent to Buenos Aireswhere the then governor Juan Manuel de Rosas decided to house them in the Santos Lugares prison, in what is now San Andrés, in the San Martín district of Buenos Aires.

when they were questioned neither of them showed regret. Quite the contrary: they sought to save their lives but without denying the love that united them or renouncing the conviction that it was unfair, and also useless, to try to separate them. To them as well as to every woman and every man who had the decision to choose himself.

Facing the firing squad, neither Camila nor Uladislao showed remorse. In them, love was stronger.

“That if this event is considered a crime, it is her to the greatest degree for having made double demands for escape, but that she does not consider it a crime because her conscience is clear,” Camilia declared, according to Enrique Molina in the historical novel “A shadow where Camila O’Gorman dreams”.

firewood and fire

When it became clear that “the girl and the priest” had fled, it was Camila’s own father, Adolfo O’Gorman, who reported what had happened to Rosas and He asked for an exemplary punishment. He wrote a letter to the Restorer describing his daughter’s escape as “the most atrocious act never heard of in the country” and requesting “give order for requisitions to be issued in all directions to prevent this unhappy woman from being reduced to despair and, knowing herself lost, precipitates into infamy.

From the Catholic Church, the anger at what happened went beyond the staunch defense of celibacy. The love between a priest and a woman it undermines its seat of privilege when it comes to pointing out to the whole society where virtue is and where sin is, where is good and where is evil.

“One of the most energetic denouncers of the scandal caused by the elopement of the lovers was someone who should have kept a prudent silence. But the impunity to which he was accustomed in that society of double standards It gave the Dean of the Cathedral and director of the Public Library, Felipe Elortondo y Palacios, the necessary peace of mind, despite his well-known concubinage with Anastasia Díaz, his servant, with whom he had a long relationship for almost twenty years,” says Pigna.

But the scandal also had political dimensions and its resolution would bring winners and losers. The relationship between Rosas and the Church had advances and setbacks. The papacy, which at first had ignored the independence governments, it tried to give some predictability to the relationship with the new nations. The Unitarians, opponents of Rosas, tried to take advantage of a fact that caused social upheaval.

The love between a priest and a woman undermines his place of privilege when it comes to pointing out to the whole of society where virtue is and where sin is.

From Montevideo, anti-Rosista expatriates launched a campaign in which presented Camilia and Usladislao’s escape as irrefutable proof of “corruption” who reigned in Buenos Aires.

From Chile, Sarmiento wrote: “The horrible corruption of customs has reached such an extreme under the frightful tyranny of Caligula del Plata, that the impious and sacrilegious priests of Buenos Aires flee with the girls of the best societywithout the infamous satrap taking any action against these monstrous immoralities.

As long as Bartolmé Mitre, from Bolivia, incited the need for an exemplary punishment At the same time, he was a true precursor of fake news by pointing out that “it is known that foreign chancelleries have asked the criminal government that represents the Argentine Confederation for guarantees for the daughters of foreign subjects who have none for their virtue.”

The debate before facing the firing squad

Juan Manuel de Rosas was torn between two fires. The demand for an “exemplary punishment” from friends and enemies, from the Catholic Church and from Camilia’s own father and the request for clemency from his daughter Manuelita and his sister-in-law Maria Josefa Ezcuerra, from whom he had adopted Pedro (Juan at birth), his unrecognized son with Manuel Belgrano, as his own.

The Restorer commissioned an opinion that could have changed history. He asked the opinion of the jurists Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield, Lorenzo Torres, Baldomero García and Eduardo Lahitte. The response of all of them, including that of the future editor of the Civil Code, was condemnatory.

Camilia O’Gorman and Uladislado Gutierrez would be shot.

No place for wimps

The only thing left to do was bring the match that would consummate the crime to the pyre. And the one who did it was Juan Manuel de Rosas himself by ordering that the prisoners were shot at 10 in the morning of August 18, 1848, in the barracks of the Holy Places. The only pious act was to give Camila holy water to drink to save the soul “of the innocent that she carried in her womb.” The young woman was pregnant.

Nothing and no one could prevent Camila and Uladislao from being shot. Neither earthly nor divine laws, which did not legitimize applying the death penalty to a pregnant woman. Not even the request for clemency that Manuelita Rosas (Camila’s friend) made to her father. Nor the proposal of María Josefa Ezcurra, Rosas’s sister-in-law, to lock Camila in the Holy House of Exercises to avoid her death.

The only pious act was to give Camila holy water to drink to save the soul “of the innocent that she carried in her entrails.” She was pregnant.

In 1871, during his exile in England, Rosas assumed responsibility for what happened: “No one advised me to execute Father Gutiérrez and Camila O’Gorman; nor did anyone speak to me on his behalf. On the contrary, all the first persons of the clergy spoke or wrote to me about that daring crime and the urgent need for an exemplary punishment to prevent other similar or similar scandals. I believed the same. And being my responsibility, I ordered the execution.”

Sarmiento did the same, but without assuming his own. Forgetting that he had called for measures against “those monstrous immoralities”, denounced that the “barbaric tyrant had the beautiful Camila O’Gorman shotof a distinguished family, while she was pregnant, for the crime of loving a man”.

Only love breeds wonder

Between hypocrites, sadists and criminals a rose can also grow. Camila and Uladislao never showed regret. They could not: love was not a crime for them. It was something much simpler and more moving: a way of being in the world.

“My Camila: I just found out that you die with me. Since we have not been able to live on earth united, we will unite in Heaven before God. He forgives you… And he hugs you, your Gutiérrez.”

“I am going to die, and the love that dragged me to the torture will continue to prevail in all of nature. They will remember my name, martyr or criminal, my punishment will not be enough to contain a single palpitation in the hearts they feel”.

Camilla O’Gorman. Uladislao Guiterrez. Love is only for those who love.