Installed in the cultural landscape since the 17th century, the laws against sodomy in the United States continued to form part of the country’s jurisprudence once independence from the Brits was achieved. The punishments for this criminal figure then included fines, life sentences or both. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several states imposed laws against any individual deemed to be a “sexual pervert.” States like Illinois even went so far as to deny the right to vote to anyone convicted of sodomy (1827). As early as the 20th century, in 1970, Connecticut denied driver’s licenses to “confessed homosexuals.”

Starting in the 1960s, every state had a law against sodomy, but it was rarely enforced in the private arena. Also, many states that had not repealed their sodomy laws had enacted provisions reducing/softening penalties. Let’s say at the time of Lawrence’s decision vs. Texas (2003), the case that now concerns us, the penalty for violating a sodomy law varied greatly from one state to another, considering that there were those that still kept their laws in this regard.

There were, however, other states in which the sentences were still harsh. Calling the shots was Idaho, where a person convicted of sodomy could receive life in prison. And in Michigan he could receive a maximum sentence of fifteen years in prison, and life in prison for repeat offenders. So by the turn of the 21st century such laws in most states were no longer enforced or were enforced quite selectively, with a few exceptions. But, they were often used as a justification to discriminate against gays, lesbians and bisexuals. In this context, the Lawrence case vs. Texas.

The case

On September 17, 1998, John Geddes Lawrence received two homosexuals, one white and one black, at his apartment in Harris County, Texas: Tyron Garner and Robert Eubanks, friends for more than twenty years. Garner and Eubanks had been in an on-and-off relationship since 1990.

The narrative of the case refers that, a little drunk, Eubanks had a jealous attack. He left the apartment, called police, and told them “a black man was going crazy with a gun” at John Geddes Lawrence’s apartment.

Four police officers arrived at the building; Eubanks told them where the apartment was, that he didn’t have the lock on the door. A first policeman took the initiative to approach in order to determine what charges to present. And he entered the apartment. There was no weapon. But he reported seeing Lawrence and Garner having anal sex in a room.

A second police officer claimed to have seen them engaging in oral sex, but the other two reported seeing nothing. The chief of police had the discretionary authority to charge them with a variety of crimes and determine whether or not to arrest them. In the end, he considered charging them for having sex in violation of the Texas state anti-sodomy law, but had to have an assistant district attorney check the law to make sure it covered sexual activity inside a home. . He was told that the Homosexual Conduct Act made it a Class C misdemeanor to “engage in deviant sexual intercourse with another person of the same sex.” Eubanks later admitted that he had lied. He pleaded no contest to the charges of filing a false police report. He served fifteen days in prison.

the courts

Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, a legal organization dedicated to defending gay rights, took the case and moved it through the Texas court system. His central point was that what happened violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment — which prohibits states from denying “to any person within their jurisdiction equal protection of the laws” — and a similar clause of the Texas Constitution.

The plaintiffs lost practically every one of the appeals. However, his attorneys believed that after the Supreme Court’s favorable opinion in Romer vs. Evans (1996), the first case to address gay rights since Bowers vs. Hardwick (1986), when the body held that laws criminalizing sodomy were constitutional, there was a chance of winning. In the first case, Supreme had ruled (6-3) that a Colorado state constitutional amendment that barred protected status on the basis of homosexuality or bisexuality did not meet the equal protection clause. The defenders then made the correct bet.

The Supreme Court

The time had come to take the case to Supreme. On July 16, 2002, the lawyers asked their justices to consider three issues. First, if his defendants’ criminal convictions under the Texas Homosexual Conduct Act, which criminalized sexual intimacy between same-sex couples but not identical behavior by different-sex couples, violated the guarantee of Fourteenth Amendment equal protection. Second, if their defendants’ criminal convictions for consensual sexual intimacy between adults—in their home, in a private space—violated their vital interests of liberty and privacy, protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. And third, if Bowers should be annulled vs. Hardwick, the aforementioned 1986 ruling that upheld the validity of Georgia’s sodomy law.

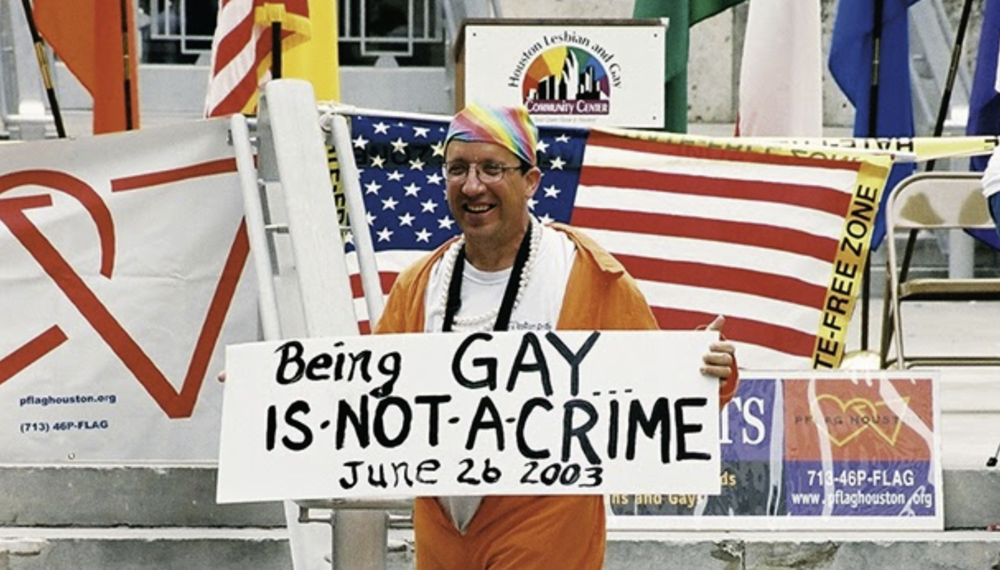

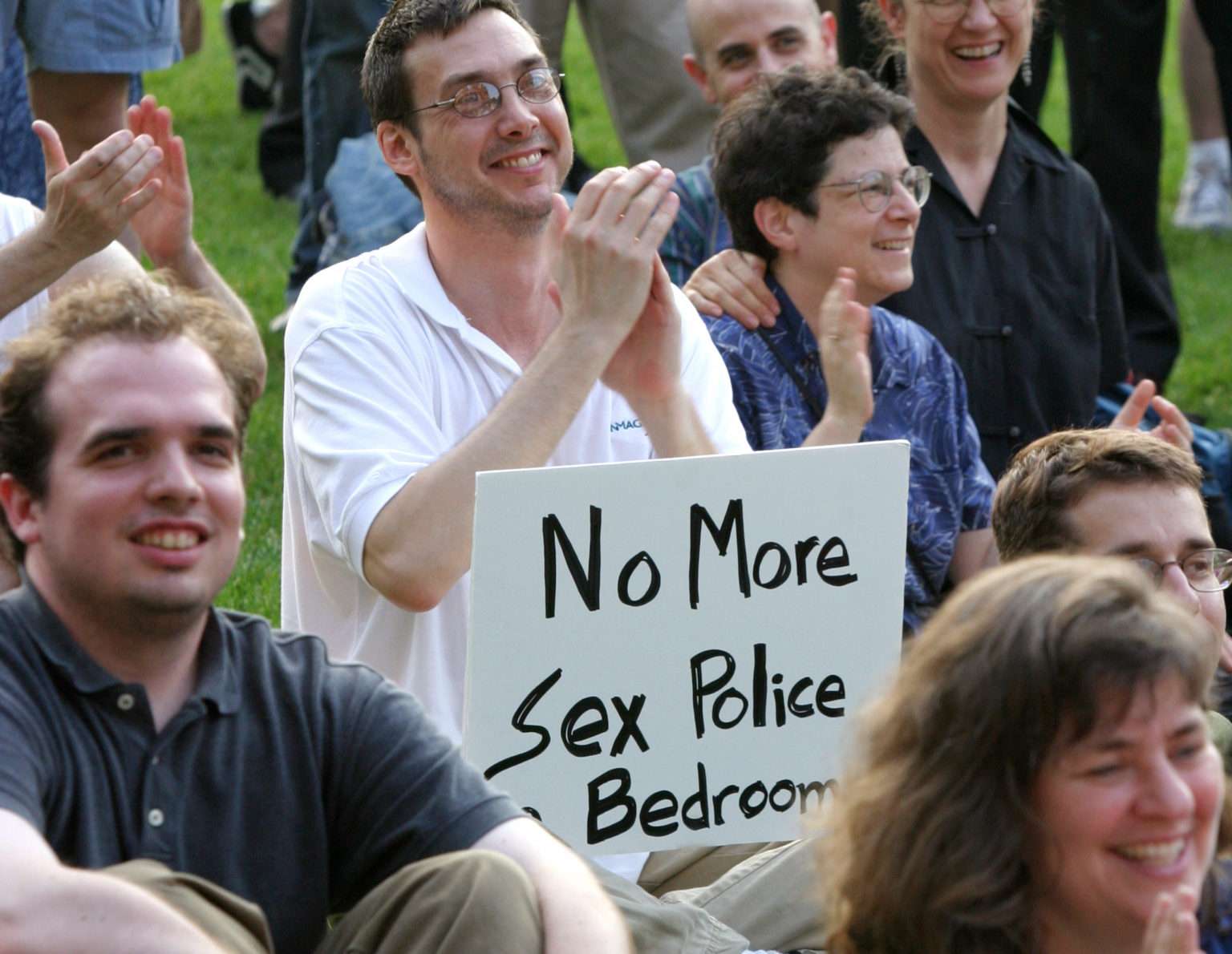

On December 2, 2002, the Court agreed to take the case. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court on June 26, 2003 struck down the Texas same-sex sodomy law and ruled that this private sexual conduct was protected by the liberty rights implicit in the due process clause of the Constitution. United States Constitution. This decision invalidated all state sodomy laws insofar as they applied to private consensual conduct. The ruling also reversed the Bowers Court ruling. vs. Hardwick. In a word, the court held that consensual intimate sexual conduct was part of the liberty protected by due process under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The dissenting opinions then corresponded to three of the conservative magistrates: Antoni Scalia (1936-2016), nominated by Ronald Reagan in 1982; Clarence Thomas (1948), appointed by George TW Bush in 1991; and the president of Suprema, William H. Rehnquist (1924-2005), proposed by Reagan in 1986.

The former wrote essentially the same arguments we have heard to this day: if the court was not prepared to uphold laws based on moral choices as it had in Bowers vs Hardwick, state laws against bigamy, same-sex marriage, adult incest, prostitution, masturbation, adultery, fornication, bestiality, and obscenity would be invalid. “Today’s opinion,” he said, is the “product of a Court, which is the product of a culture of the legal profession, which has largely adhered to the so-called homosexual agenda, by which I mean the agenda promoted by some homosexuals, activists aimed at eliminating the moral opprobrium that has traditionally been associated with homosexual conduct”.

Lawrence vs. Texas was, without a doubt, a great step forward for the gay rights movement in the country. And helped lay the groundwork for the Obergefell case vs. Hodges, who recognized same-sex marriage as a fundamental right guaranteed by the United States Constitution.

Ultimately, the case was paramount in two ways. First, and most obviously, it established that private and consensual homosexual sex is part of a substantive right to liberty protected by the Constitution. Second, and less obviously, it held that “fundamental rights”—that is, “substantive due process” or activities implicitly protected by the Constitution—are broad principles under which numerous individual conducts can be protected. This also undoubtedly constituted a radical departure from the conservative methodology of the Court during the 1980s and 1990s, which found evidence of fundamental rights only in activities that the laws themselves substantially protected (“history and traditions”). In the end, therefore, Lawrence vs. Texas protected the privacy of individuals in their bedroom and renewed the Court’s power to identify individual rights above and beyond those historically established/nominalized by law.

Legislating in the opposite direction is what has led to the annulment of Roe vs. Wade appealing, among other things, to a literalist and fundamentalist reading of the Constitution.

But the current conservative majority on the Court has an ideological goat’s leg on their minds. And they will continue to use it. They have plenty of time.