The news from just a few days ago circulated in the network of networks without much resonance, perhaps to be consistent with the headline: Silent wave of suicides hits indigenous communities in Colombia.

He was talking about the indigenous people of the Colombian Emberá Dobida community, where 22 suicides had occurred in the last quarter, 20 of them involving minors.

The text explained that they suffered from ‘wawaima’, understood in their cosmogony as a spiritual malaise that could resemble depression in the Western world.

But that report is only the tip of the iceberg, a glimpse of what the indigenous communities of our America have suffered during these years of pandemic.

Not for pleasure the XV General Assembly of the Fund for the Development of Indigenous Peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean (FILAC), carried out in Bolivia between October 28 and 29, alerted the world that indigenous peoples were in danger of extinction due to Covid.

Said Assembly, the highest government instance of FILAC, made up of government delegates and representatives of the indigenous peoples of the Member States of the United Nations, began with an ancestral ritual of gratitude to the “Pachamama” or Mother Earth, the same today he is watching them suffer and die.

Sufferings of those sons of America

“I am a son of America and I owe myself to her” is a reiterated Martian phrase, and in order to be consistent with it in practice, it would be necessary not to see as alien or as a matter of second order those sufferings that today afflict native peoples.

That “continental soul” invoked by Martí should shudder with terror and mobilize urgently to learn that, only in the region of the Americas, where the indigenous population numbers more than 62 million people, until last July the coronavirus had infected 617 thousand , especially in the Amazon region, and had killed almost 15,000.

At the same time, the pandemic exposed and fiercely deepened the inequalities suffered by these peoples in terms of health and education. In the latter, the technological gap caused significant damage, considering in particular the alternative of distance education in times of confinement.

The other impact they suffered as a result of Covid-19 was in the economic order: “the indigenous people who are at the urban level lost their jobs and those who live in the countryside lost their crops because they could not sell them due to the confinement,” he summarized Myrna Cunningham, president of FILAC.

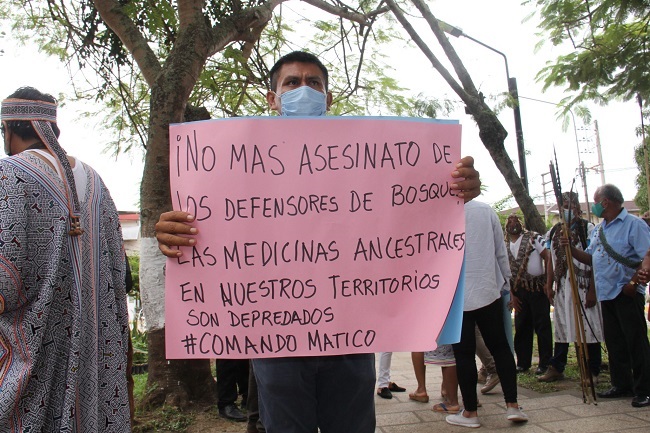

To this is added the occupation, invasion, of indigenous territories by companies, other private ones, and even by drug traffickers.

The latter is the case of the indigenous people of the Central Amazon of Peru, for example, where the hundreds of native enclaves that live there they have denounced the expansion of the coca growers in their territory.

To such an extent has been this invasion of illegal coca crops, clandestine laboratories and other aspects of this illegal activity, which have occupied more than 24 thousand hectares of only three communities of the Kakataibo people.

And with that eviction comes deforestation, which in this case does not imply a greater impact on climate change but rather means a shot to the chest of indigenous survival because the forests are their food, their medicine and also the axis of their beliefs and spirituality.

To make matters worse, along with deforestation, drug traffickers have also uncovered a wave of assassinations of native leaders.

Nearly 40% of the indigenous people of Latin America are currently outside their native territory, and not because they have decided to emigrate but because of pressures such as those mentioned and that, if they persist, would lead to 70% at the end of a five-year period. the proportion of these inhabitants forced to move away from their land.

Said forced migration, as well as the death of older indigenous people, have put the survival of various cultures in South America and also in the Caribbean at risk.

“I would say that what has affected the indigenous people the most is the death of the elderly, the wise, those who know the culture, the languages. There are some peoples that have very few speakers and losing the oldest ones the enormous risk that these cultures will be totally lost. There is a real danger of extinction for these peoples, especially in South America and Mexico, “said Cunningham.

Solutions at hand?

The obstacles to overcome in order to guarantee a dignified and full life for these original communities are great and complex.

But FILAC’s technical secretary, Gabriel Muyuy, believes that the capacity of these peoples can contribute to an understanding with the different governments in order to integrate all of them to post-Covid solutions.

Two main paths can be differentiated in this strategy for the post-pandemic: health and the socioeconomic sphere.

For the first, programs and projects for intercultural health would have to be set up, which, in addition to curing diseases, deploys a comprehensive approach that ranges from environmental to cultural health.

Those who in this time of Sars-Cov-2 have undertaken the task of vaccinating these communities, know how many differences there are between that world and the so-called Western culture. Even rituals and dances sometimes precede the moment of the prick, discounting the language barriers that make explanations difficult.

Regarding the socioeconomic reality to be transformed, FILAC has defined the Indigenous Cooperation Initiative for Good Living program, which includes the contribution of tools and other tools and implements that allow these peoples and their leaders to achieve autonomous development.

At the same time, it includes providing them with spaces for a better commercialization of their products and, at the same time, acquiring those that they do not produce and need to survive.

The Brazilian Ro’otsitsina Juruna, from the Xavante people, in the Namunkurá community, Mato Grosso state, when being interviewed for a journalistic series on human rights and pandemic, wisely summed up how these peoples could get ahead:

“I think that only through knowledge, talking about what human rights are, can we achieve some progress. But it is not enough to educate indigenous communities, talk about human rights, if these rights are later violated by the State.

“We need to know what we can do to defend our rights and make them effective in fact,” he concluded.