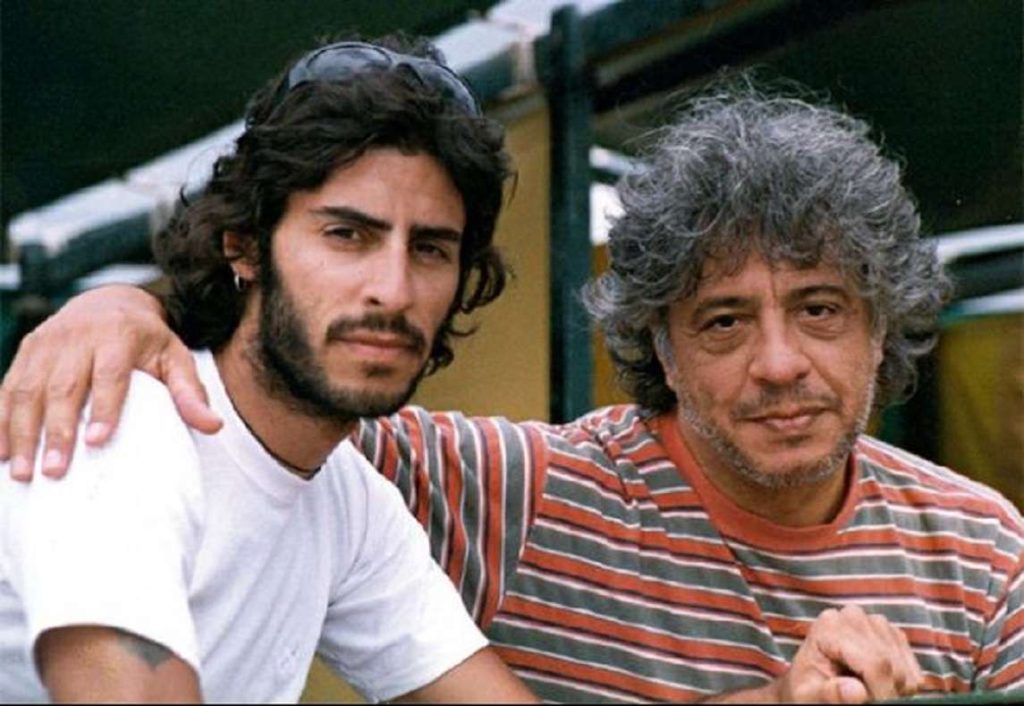

Tute (Juan Matías Loiseau, Buenos Aires, 1974) has memories of caricaturists like Boligan and Falco. Sometimes he collected materials so that these and other Cuban colleagues could carry out their work in precarious Havana at the end of the 90s. The animation work that Juan Padrón did with Quino’s work, especially with Mafalda, also comes to mind. Shut up. Think. He finally says: “Quino didn’t like it very much.” Silence.

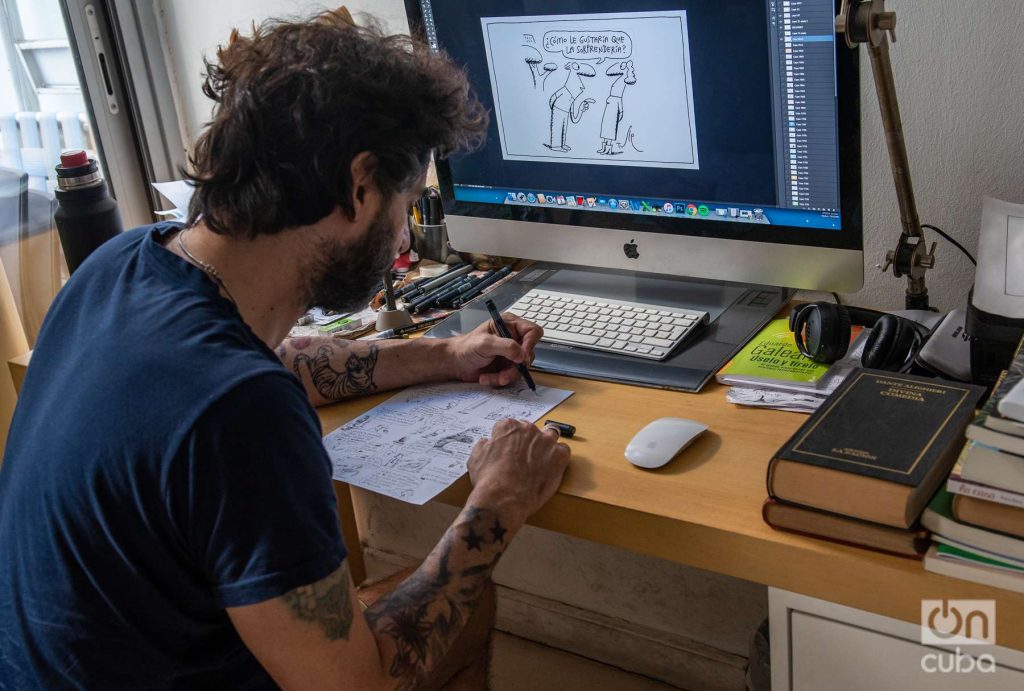

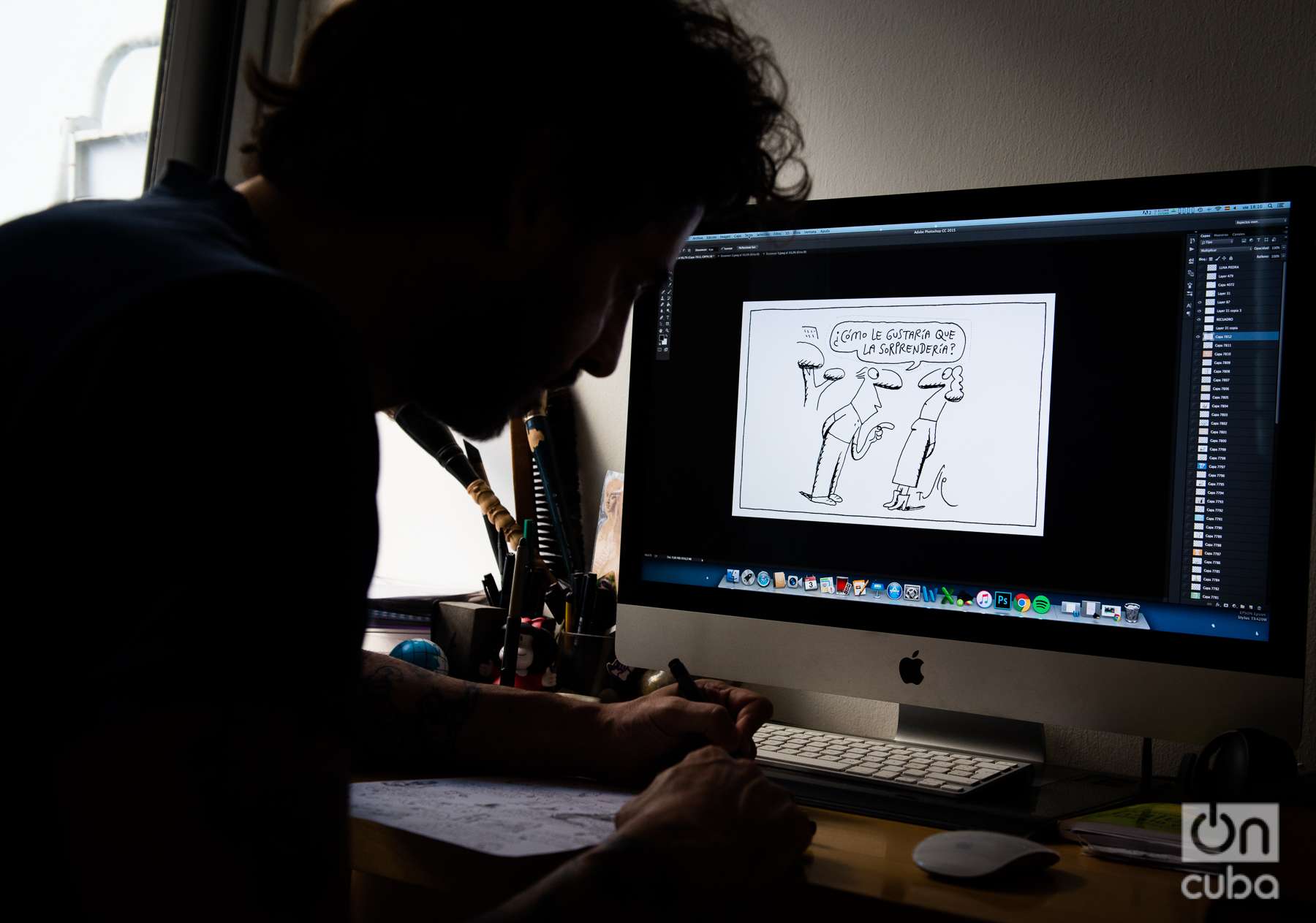

In the apartment, located in the stomach of a modern building with “harder than reality” doors. Silence prevails. Outside, the city burns. And it does not escape this part that, with its narrow streets, its towers and people, is the most Havana area of Buenos Aires.

We talk about the characters and the voice that the cartoonist has in his head about them. Ever should have encouraged one of his: Batu. He did it for the Pakapaka children’s channel and it was so difficult for him to find the appropriate tone that he interviewed almost thirty actresses.

“Everyone has their voice and you have to make the voice that you choose match the voice that each one gave the character.” In this sense, he considers that his father, another famous Argentine cartoonist, Caloi, had more success when adapting his classic Gracious. “He found a voice that was half the voice that we all had from Clemente; and if it was not that, it was better than the one that each one had”.

“It’s difficult to bring Mafalda to cartoons,” he points out, returning to the subject of Padrón’s adaptations: “Giving her a voice was difficult and not voicing her was difficult as well. How are you going to make Mafalda speechless when her strength was what she said? The animations were very good, but the transfer failed ”.

“…and Quino was reticent, quite difficult”, he points out.

Like me, many friends follow Tute’s works. It has fixed spaces in newspapers such as The nation, He publishes books and shares his creations and projects on social networks. Prior to the interview, I bought and read his second graphic novel, “Diary of a Son.”

He wrote it years after Caloi’s death and collects pain and obsessions. He starts with a representation of himself. He is stretched out on a divan, he tells the psychoanalyst that he has decided to make a book in which he reads from his birth to the death of his father.

—When was the first time you went to therapy?

“A long time ago, thirty years ago maybe.

-Because?

“First, out of curiosity. It was something that interested me. In my house, my old man was psychoanalyzed. My old woman was a social psychologist; there was always talk of reading between the lines, interpretations were made and for me it was like a language that I did not master, a language that I did not master. She listened to her, but she did not understand how these conclusions were reached. I always found it interesting, but very foreign. She listened to him, it was music.

The table we are sitting at in his house in San Telmo is round. In front of Tute, a bookseller where there are many titles related to his profession; a good part of them in English, like The world encyclopedia of comicsby Maurice Horn. I see books by João Fazenda, EC Segar, his contemporary Liniers and great influences on his formation, such as Sempé and Steinberg. In addition, objects of utilitarian and decorative purpose can be seen: a fist like plaster; a cartoon of Mafalda made by Quino; another Mafalda, but made of plastic; a wooden horse whose legs rest on seesaws on the floor, in front of the bookshelves. He belonged to his mother.

Tute has written three books to unravel the subject of the unconscious: tutherapy, couch humor and superego. All published by the Sudamericana publishing house.

“One starts out of intrigue, out of curiosity and then quickly finds reasons to stay on the couch and start working. I remember that mine was motivational”.

Entering Tute’s brain is easy because he is not afraid to open the doors of his soul in each of his works. The things that one hides and that only happen in the depths of the mind, remain in plain sight.

“I suppose —he ventures— that it has to do with my interest in psychoanalysis, as a reader of psychoanalysis and as a patient. I think that once one passes by the divan he also changes his gaze on everything, on all reality; about the personal, the intimate; but also the gaze on politics, on the social situation”.

There is something very mental in this fact, I think, very rational; but the cartoonist associates it with other matters more determined by creation itself and with the mysterious ways in which it appears to us: “I associate it with art, with poetry, with humor. These two components are present in psychoanalytic practice: humor as an enabler and poetry as a synthetic effect and as a permanent search for the meanings that are hidden behind the word”.

Getting into Tute’s brain, I repeat, can be very easy. From leafing through some of his books, like this one I told you about, diary of a sonone can go through it like Dante in the journey that he sang in his Divine Comedy, a work that comes to mind because it is a book that Tute is reading these days. I see two copies on your work table. “I am extremely fascinated with the Divine Comedyreading and studying.

Let’s walk through his brain. Let’s make it easy. Let’s put it this way: there is an unconscious production zone, a vacuum cabinet like in the containers for Physics experiments where a cabinet and two chairs float. There is a forest called Bosque de Las Dudas and a gloomy and unpleasant Grotto that ends at the edge of Lethe.

—Humour, poetry, psychoanalysis and philosophy could save people’s daily lives —I summarize what he told me.

“I think so,” he replies. Note that we produce humor because we are aware of our finiteness, of our death. In the animal kingdom we are the only ones aware of death and therefore we have the need to produce humor, to save ourselves, so as not to shipwreck.

—You are a Borgean in that sense.

—It is Borgean in the sense of turning it into a kind of wood that one clings to in a shipwreck.

—It’s something Argentine too.

—Humanity is like that, we all produce humor. Note that in moments of greatest tension what relaxes is humor. What appears as a facilitating effect of something is humor.

Tute tries to make his humor as timeless and universal as possible. “It is not tied to the news of the political or media agenda.” He also does not believe that the times we live in, so determined by social networks and the heyday of memes, affect art or, at least, the view he has of the world. Nor does it deteriorate his sense of humor: “The meme responds to a need, to a social demand of this time. Which is it? Make it brief, fast, concise. Because there is little time. Synthesize for a moment. Also, it gets old quickly.

Tute’s apartment is located a few blocks from Defensa and Chile streets. At that intersection are the figures of Mafalda, Susanita and Manolito, because that is where the building is where Quino created those characters. The geographical proximity is only coincidental; However, Tute’s life in many ways is marked by the relationship with a universe of humor and graphics in which Quino stands out.

“I dreamed of getting on Quino’s radar. That was my dream, and that dream was widely surpassed from a call he made to me, for the published works ”.

—Did you feel the need to be recognized by Quino?

—When you start, you dream of being recognized by your teachers. There was a part of the road paved by my old man; but there was another that was more dangerous, for being the son of who he was. The part of the paved path is that he had access to those cartoonists and the most uneven part is that you later have to be aware that you are on the same path as your dad. But, I think it was much more smooth than complex.

Tute was in Cuba in the early 2000s. It was a trip to learn, he says. “I stopped at the house of a married couple who were already separated, but since they could not access a house they continued to live together. She, pretty, was anti-Castro and he was a Castro police officer. He, very serious, and she very nice. It was fun”.

He also remembers that his father, Caloi (Carlos Loiseau; Salta, 1948), was once in Cuba for an event linked to the San Antonio de los Baños International Film School. Then he met Fidel Castro, to whom he even asked why there were no caricatures inspired by him in the Cuban press, if anything they were prohibited, to which Fidel replied that anyone could make a caricature of him… as long as they did not carry out a counterrevolution.

In the novel written after the death of his father, Tute assures that he has been a Peronist since he was born, because he cried all day when, a few weeks after his birth, Perón died (at least that’s what they told him). In his house there was a portrait of Perón that his sister was led to believe throughout her childhood that it was his grandfather.

—Can the political be controversial for the creator?

—I always had the example of my old man, who was a Peronist and published in Clarion. She always found the way around to say what she needed to say. It was not controversial. If I have to analyze it today, after twenty years of publishing in The nation, I realize that he played me in favor. He was good for me, because he forced me to do an exercise that is always healthy: subtlety. He improved me as a cartoonist, as an artist.

—And this time of political correctness, of mass attacks on the networks?

—There are times that have made me think, reflect and change things; others, no. We are victims of a political correctness that is very dangerous. It is on the sidewalk of solemnity, and graphic humor is on the sidewalk in front. This political correctness and this culture of cancellation for art are very harmful. I believe much more in critical thinking and in the possibility that everyone can express themselves as they want and, in any case, one can agree or not, with some limits that, of course, every society must have to live together.

The afternoon was an oven. Buenos Aires had been hit by a heat wave for days that kept people drinking liquids and produced some orange sunsets as if we were being absorbed by the sun. Sometimes you smell smoke, even in these narrow streets in an area that reminds me of Havana. The reality does not change when leaving Tute’s department. The city and the people that he reflects in his drawings every day, are waiting for me out here.