The only difficulty one faces when interviewing Yovani Bauta is establishing the time line. In none of the many documents about him that I have consulted is his date of birth recorded. He has the appearance of a 50-year-old man, an age that is more than improbable if we take into account that in the 80s of the last century he was already an active and well-known artist in Cuba. We know that he landed on this planet in the province of Matanzas, that he studied at the National School of Art and at the University of Havana, where he graduated in Law. And a little more.

To the researchers of the future who will curse me for ignoring such interesting information, let me say that I did what I could. Yovani responded with an ironic smile and a flirtatious phrase at my request: “I am the age I appear to be. Put what you want there.”

We had met several times in Cuba and, although we were not friends, there was a certain current of sympathy between the two of us, which is not difficult in his case. He is an assertive man; that is to say, that he issues and maintains his judgments without trying to impose them, that he rejects any idea or proposal that seems inappropriate to him with a composure and joy as if he were accepting it.

So I was happy to contact him in Miami, spend an entire afternoon with him in his studio and verify that he is still an empathetic, curious, smiling, talkative being with a long memory. But, more than all that, I was delighted to see that Yovani is an artist of constant searches, but, above all, of discoveries.

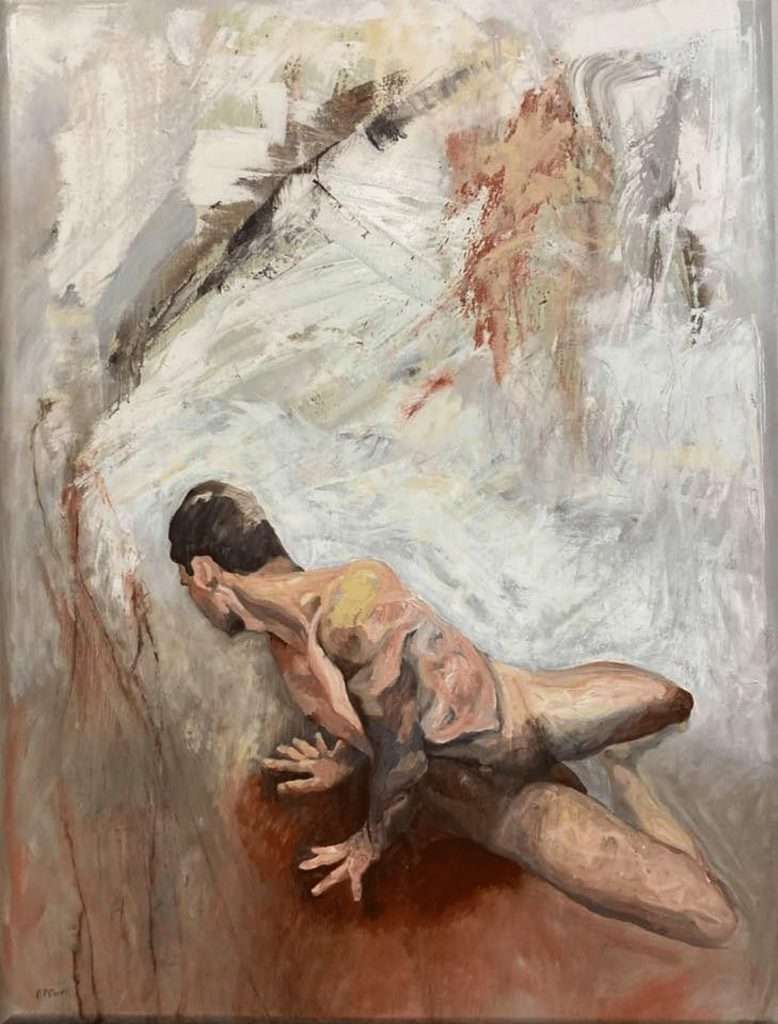

Figurative as he is, he has made the human body his main object of study. His characters do not respond to pre-established models. He paints “from memory” compositions that have been forgotten, men and women in an existential weather that seems to be his own. His works cause me the same desolation as those of Fidelio Ponce, although there are not too many concomitant points between them in terms of visuality.

I share here the notes of that afternoon of art and friendship.

From what I see, your path in the visual arts was zigzagging at the beginning. There is a long blank space in which you studied Law and even came to practice the profession at very high levels; then you “reunited” with your original vocation.

My life has been a search for paths and motivations. I have dabbled in the field of Law, visual arts, writing and theater. I studied the race to please my mother and my girlfriend at that time; I exercised it out of curiosity, and I abandoned it because they forced me to.

Do you want to talk about it?

No. I don’t feel like it. I owe you the story. Maybe sometime I’ll write it. Those were dark times. It’s been a long time since I turned that page.

Thanks to the pressures that took me out of the practice of law, I returned to the plastic arts; I dabbled in humorous theater while resuming my original career. In other words, I painted and acted during the 80’s, very satisfied with both actions.

When, how, did you assume yourself as an artist?

Since childhood he was attracted to painting. He took my first steps in junior high school, with classes to appreciate the plastic arts. I continued, later, in the Tarascó academy, which was considered equivalent to San Alejandro and which later became the Provincial School of Art of Matanzas; this was in the night course. I definitely considered myself an artist at the end of 1968, at the National School of Art, when I was in my first year.

Your first personal exhibition was of drawings (1989), at the Matanzas Gallery. Since then, your curriculum adds thirty-six individual samples.

I participated in various collective exhibitions in the 1970s: in the First Hall of Young Creators at the National Museum of Fine Arts, in Havana; in the Uneac Gallery and in the Matanzas University Center, among others. But since there was a pause in that path when I dedicated myself to practicing Law, it was in 1989 when I made my first important personal one. Since then, I have exhibited in Spain, France, the United States, Switzerland, Mexico, Argentina…

Among so many exhibitions, which do you consider the most important?

I choose two recent ones: invisible presence, at the Miami Dade College Museum of Arts and Design, July-August 2013; Y White pages, at the Cultural Center of Paraguay in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and at Irazoqui Gallery, Miami, United States, 2019 and 2020 respectively.

How has your work evolved? Can noticeable breaks be observed?

I have had a great learning experience since I left Cuba. Visits to important museums and galleries in Europe, Latin America and the United States have been essential in the process. Observing originals is quite a formative experience, just like meeting the most important figures in contemporary art. This has nourished and conditioned me to an evolution in which the subject of my work (the human body) has been changing in its forms and ways of expression.

Characters, children, appear in many of your paintings in situations of vulnerability. Something is stalking them: a wolf, the gaze of the other, the rough sea… Do you think that living is dangerous? Do you have a tragic sense of life?

I have an optimistic sense of life, but with a sharp perception of social problems.

But your work is not properly festive.

Not dark either.

My childhood in a provincial neighborhood in Cuba, and later assuming the condition of an emigrant, have kept me within a social and cultural marginalization that encourages me to grow as a person and to denounce what assaults me in some way. The vision of the unprotected child is a symbol of human fragility in the face of dominant currents in the world.

Do you define yourself as a “rabid” figurative? What is your opinion of abstraction?

I am figurative, but I greatly admire abstraction, all its expressions. In fact, the backgrounds of my paintings are close to abstract expressionism.

You have made installations and performances. Are you interested in continuing to explore those genres?

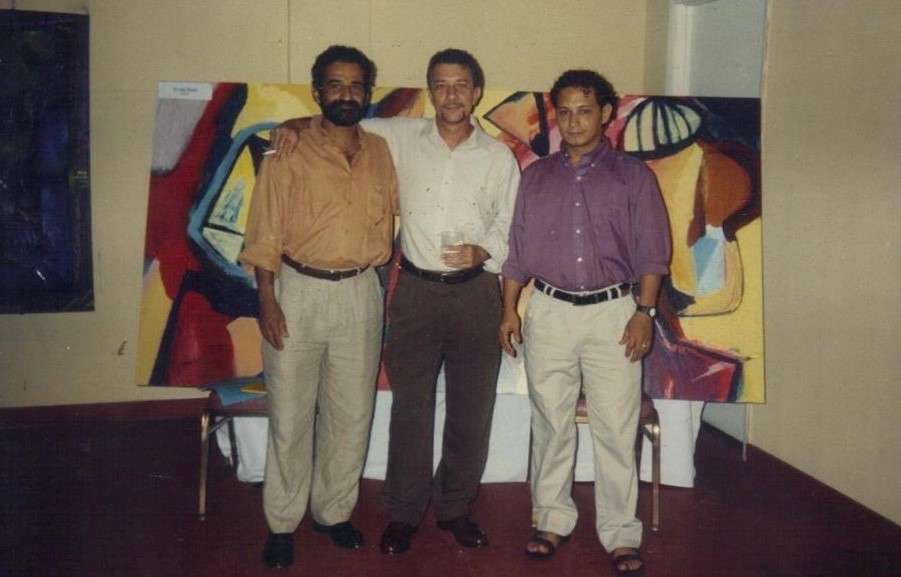

I made performances together with my dear colleague and friend Leandro Soto, in Mexico and the United States. Currently I focus more on two-dimensional art, although I do not rule out installations as forms of political-social discourse.

What relationship do you have with criticism? Do you think your work has received enough attention?

I always expect more from specialized criticism. I have been the subject of friendly criticism in general, but the problem is that we are increasingly short of sharp and bold critics. No, I don’t think I’m very cared for by her.

How are you doing with the market? In these times can you live from the brush?

I have the benefit of having worked for seventeen years at a university in Miami, which allows me to live from my retirement without problems. I don’t need to sell the work to support myself and, therefore, I don’t have pressure from anyone when it comes to creating.

Matanzas. What thoughts and feelings does this word move in you?

Matanzas is for me the small homeland, the motherland, the seed to which I must return each time in time to drink from its springs.

Would you exhibit your recent work in Matanzas?

Clear. If you allow me…