August 18, 2024, 10:09 AM

August 18, 2024, 10:09 AM

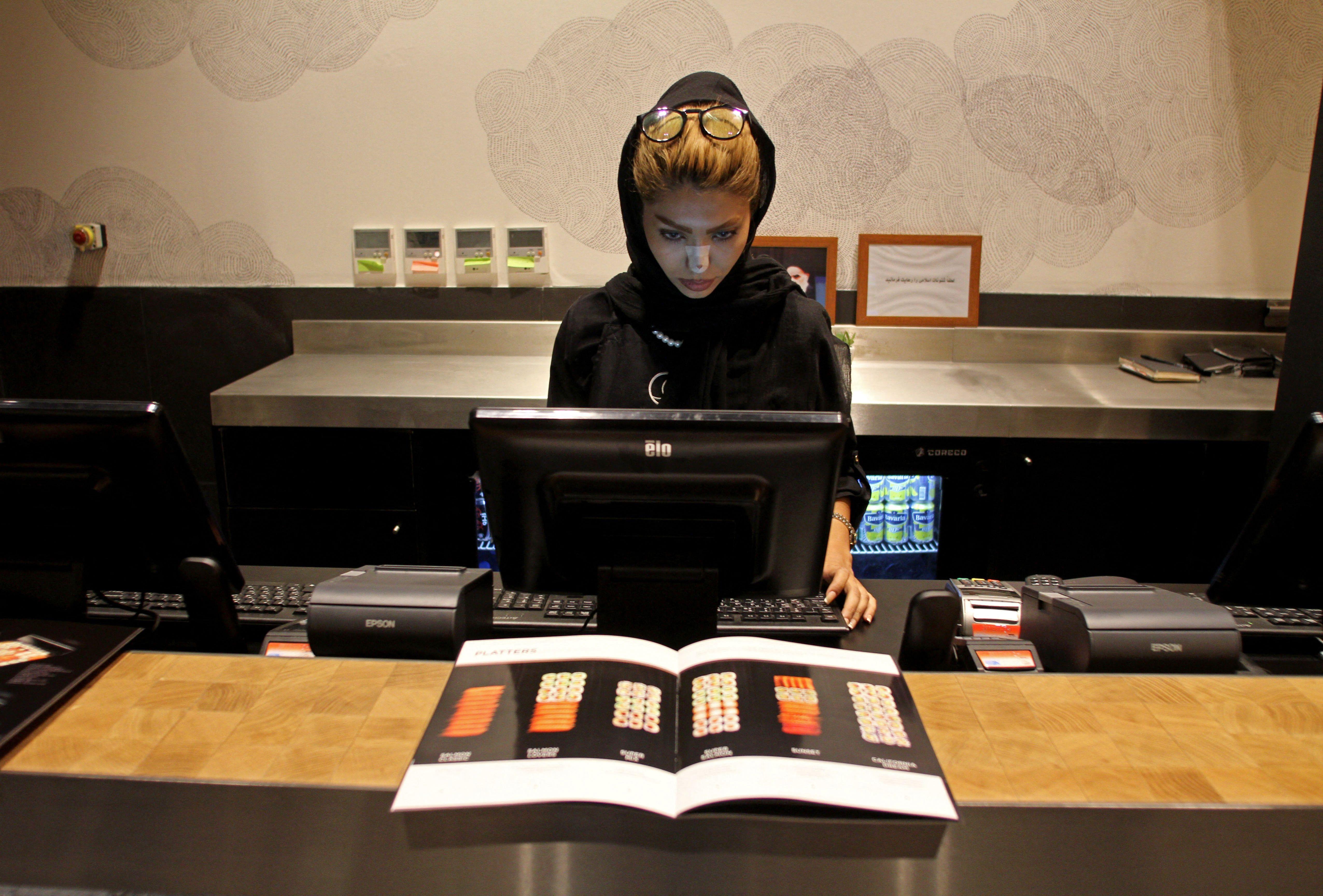

“At a job interview, I was asked to submit a written statement from my husband to prove that I had his work permit,” says Neda, who holds a master’s degree in oil and gas engineering from Iran.

The woman explains that she felt humiliated.

“I told them that I’m an adult and that I make my own decisions.”

Your experience is not isolated.

Legally, married women in Iran need their husbands’ permission to work, one of the many legal barriers they face when trying to enter the workforce.

A 2024 report by the World Bank ranks Iran among worst countries when it comes to legal gender barriers for the labor force (only Yemen, the West Bank and Gaza rank lower).

And other statistics reflect the same.

According to the recent 2024 report Global Gender Gap According to the World Economic Forum, Iran has the lowest rate of female labor force participation among the 146 countries surveyed.

While women make up more than 50% of the country’s college graduates, they are only 12% of the workforce, according to 2023 data.

Gender laws, coupled with widespread sexual harassment and often sexist views about women and their capabilities, make the work environment quite hostile for them.

Most of the women the BBC spoke to for this article said they felt they were not taken seriously enough at work.

“A number of legal and cultural barriers keep women out of the workforce in Iran,” she says. Nadereh Chamlouformer senior advisor to the World Bank.

Chamlou adds that factors such as the lack of legal frameworks and existing legal constraints, as well as a very wide gender pay gap, contribute to women’s limited participation in the workforce in Iran.

It is legal… and cultural

Men know that they can legally prevent their wives from working and some make use of this privilege.

Iranian businessman Saeed tells the BBC that “an angry husband once stormed into our office waving a metal bar in the air and shouting: ‘Who gave you permission to hire my wife?'”

He says he now makes sure to seek written permission from the husband when hiring a woman.

Razieh, a young professional working in a private company, recalls a similar incident when an angry man stormed into her office and told the CEO: “I don’t want my wife to work here.”

The CEO, Razieh says, had to tell the woman, who was an accountant, “to go home and try to make things work with her husband, otherwise she would have to resign, which she eventually did.”

According to the international advisor Nadereh ChamlouThis legislation also causes many companies to refuse to hire young women, as employers do not want to “invest in the training of these women if they later get married and their husbands take them out of work.”

And even if they do get the job (not without first fighting against their own families and spouses), women enter a labor market where discrimination is, to a certain extent, supported by law.

One of those laws is the Article 1105 of the Civil Code of the Islamic Republicin which the husband is defined as the head of the family and the ““main breadwinner of the family.”

This means that men are given priority in employment over women, who are also expected to work for a fraction of the pay compared to their male counterparts if they are offered a position.

Raz is in her 20s and has changed jobs several times. She says that everywhere she has worked, women’s jobs are the first to be sacrificed.

“At the last place I worked, when there was a restructuring, Almost all of the people who were fired were women“, he adds.

Another woman who asked not to be named tells the BBC she decided to leave her job after more than a decade and stay at home “because I knew I would never get promoted.”

“As long as there were men available, even if they were less qualified, I would never be considered for a pay rise or a promotion. It was a waste of time,” she says.

The fact that women are not legally considered breadwinners affects their right to receive benefits and bonuses.

In many cases, if they qualify, “the benefits they accrue over their years of employment might not apply to their families, such as their pension,” Chamlou says.

“They are therefore reducing the remuneration that women earn from their work and can contribute to their families,” adds the former senior adviser to the World Bank.

Sepideh holds a master’s degree in arts from the University of Tehran, where she used to teach and lead independent art projects, but has not worked in recent years.

“After I graduated, I thought I could make a living like many of the men I knew, but the social, political and economic structure is designed in such a way that makes it A suitable professional career is an unattainable dream for women“, Sepideh tells the BBC.

The compulsory hijab law was at the centre of widespread protests in Iran two years ago and remains one of the main issues of contention and political dissent in the country.

The law also makes a number of jobs, particularly in government and the public sector, inaccessible to women who do not want to conform to some of the stricter forms of the hijab.

The “loss of the environment”

“In Iran, there is also what I call the ‘loss of the environment,'” he says. Nadereh Chamlouand goes on to explain that it refers to “middle-aged, middle-class, secondary-educated women who do not work.”

“The legal permission of husbands to work, coupled with the lower retirement age for women in Iran, which is 55, pushes out an older population that in other countries is normally in the workforce,” she says.

Iran’s economy has been crippled by sanctions and mismanagement.

An IMF report indicated that economic growth is correlated with greater female labor force participation, estimating that If female employment rates in Iran were brought up to male employment levels, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) could increase by around 40%.

According to Nadereh Chamlou, there is currently no “active or conscious political will” to facilitate changes to incorporate women into the workforce.

But she believes women in Iran are taking matters into their own hands and creating small, independent businesses to open up the job market for them.

“Some of the most innovative business ideas, from cooking apps to digital retail platforms, have been started by women,” she explains.

She sees a “real private sector in Iran” made up mostly of companies owned by women.