As time goes by — at least in my experience — one becomes more reaffirmed in one’s uncertainties and incorporates some certainties. Among the latter is that art, in addition to all the other certainties attributed to it by theorists of the subject, has the function of accompanying. Also — and I continue speaking of personal convictions — that it is the only antidote to the devastating effects of death.

That is what I think about in a mountain house in Aguas Blancas, in the municipality of Dúdar, facing the Sierra Nevada in Granada, which even in May displays its white and icy headdress. I am having breakfast with a married couple who are friends and who are welcoming me, in solidarity, in the second stage of “the days of Hispania,” my intense journey through four regions of the Iberian Peninsula. She is Mexican; he is Spanish. Meeting each other, whether in Mexico City or in Havana, is what Lezama would call “an unmentionable party.”

We chatted in a relaxed manner about the divine and the human, although more about the latter, since one of our main concerns is the maddening march of the world and its dangerous inclination towards rancid fascism, which is struggling to return with renewed strength.

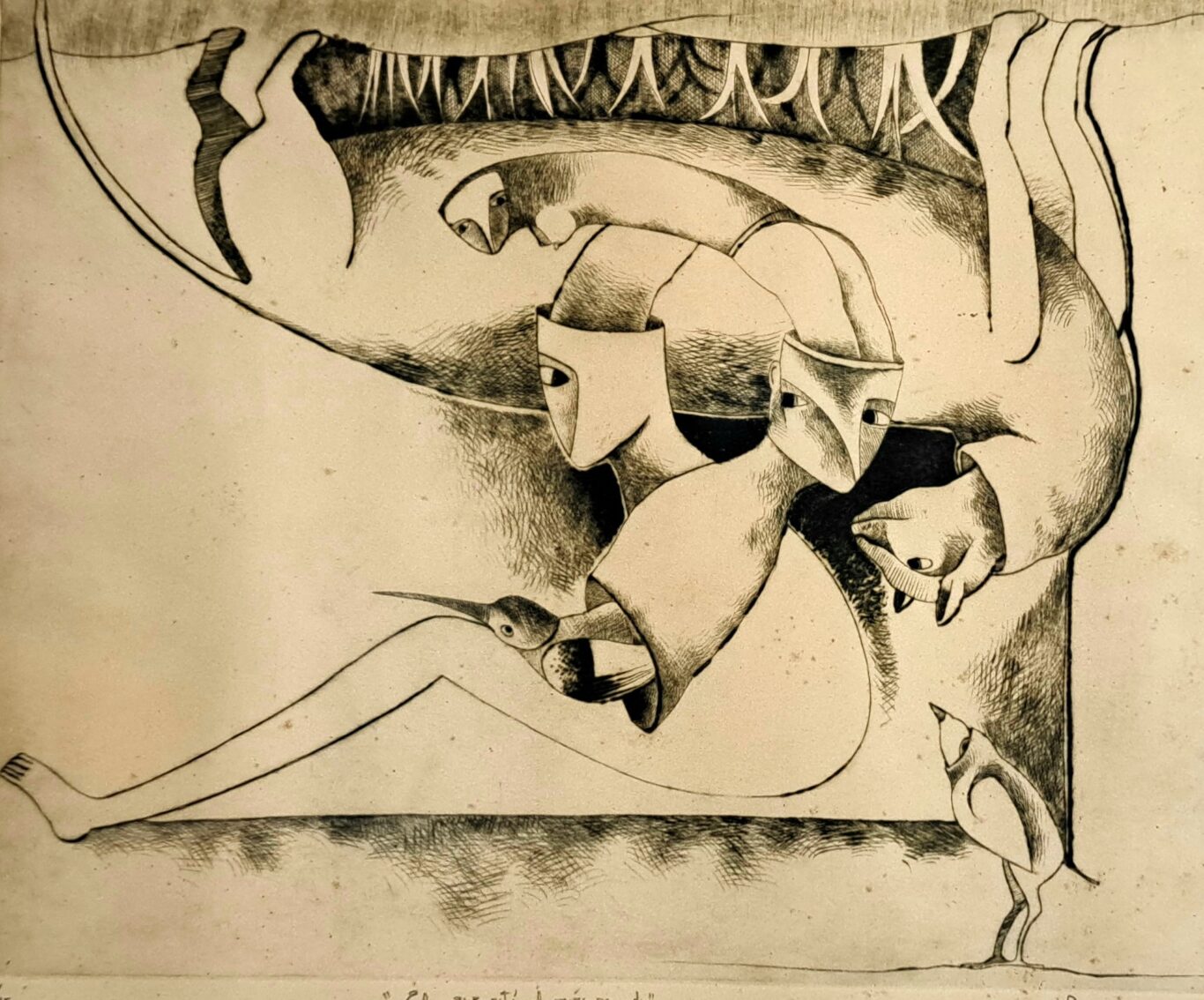

Meanwhile, I look at the handful of works that are housed there. They are by Cubans. How far they have traveled! I think. I recognize pieces by Mena, Finalé, Andy and Ignacio Mérida. And among them all, I am struck, for different reasons, by a bronze and an etching by Vicente Rodríguez Bonachea, an artist who passed away prematurely. The small sculpture, Angel with broken wingbelongs to a series of three, cast in Havana, that I was producing for him. The etching, entitled The one who is upside down is youis part of an edition of 15 prints printed, numbered and signed in Florida; number 8 hangs on the walls of my living room.

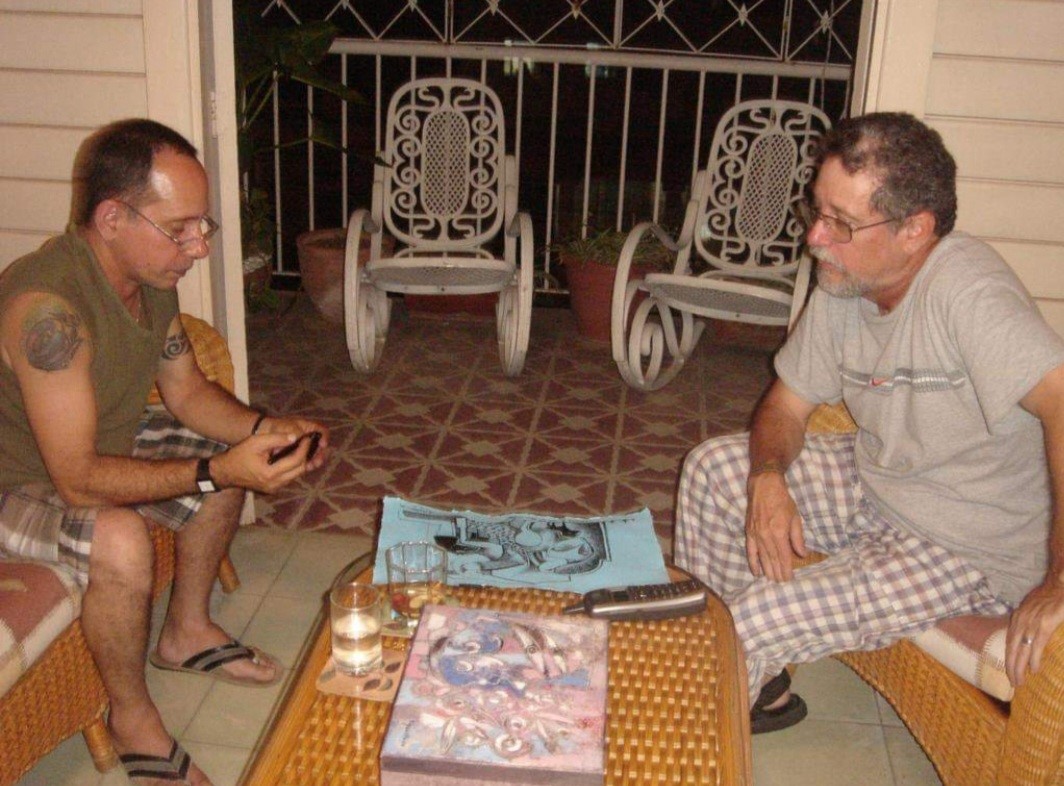

So Bona was winking at me. Reminding me of our friendship, born and forged in the last years of his life, when nothing foreshadowed the abrupt end. We have been convinced that friendship is something of childhood and, stretching the rope a little, of youth. That friends are those from school and the neighborhood, acquired in the formative stage, and that from then on we can only incorporate more or less close acquaintances into our catalog of affections. Well, with him the pattern was broken. We knew each other, we knew our respective jobs, but we had never exchanged a word.

One day in 2007, someone introduced us at an exhibition. From then until 2012—today, July 20, marks twelve years since he passed into the unknown—we were inseparable. He was a pertinacious and intelligent reader, a cheerful guy, with a joy that contrasted with the hard conditions of his life. He had been left entirely in charge of Gaby, his son who had been attacked by meningitis in the first months of life, and he gave him the most careful attention, surrounded by the daily difficulties in obtaining the food and accessories that his state of health demanded.

We worked together on several projects. In addition to casting these small-format sculptures, we designed a book with the drawings he invariably made in bars and restaurants, on paper napkins, coasters and doiliessometimes using the spilled liquor or coffee as a pigment or solvent. We took it to the final art stage thanks to a promise from some Colombian businessmen to use it as a basis for the launch campaign of a rum brand. One bad day our “sponsors” disappeared without explanation, and never responded to our messages again.

I, naturally, felt frustrated and furious. We had invested many hours in that project, which would become a splendid art book. On the other hand, Bonachea seemed to be amused by the lack of rigor of our interlocutors. He frequently spoke to me about what we should do when the Colombians paid us, a series of crazy actions that ranged from buying a malt pipe and a truckload of masarreales to take to Ciudad Libertad at recess time, as a donation for the students; to a safari along the banks of the Toa River touching up the polymitas whose colors had been faded by the sun and the rain…

I was talking with my friends in Granada, but I couldn’t stop thinking about Bona, his unique work, and his peculiar sense of humor. For that book, which we came to call Of bars and taverns —parodying a bolero, a genre he liked so much— I collected quotes from famous drinkers that he naturally incorporated into his conversations, so that later I didn’t know if those witty ideas had occurred to him, dictated by alcohol, or were from some other hallucinated person.

I remember some phrases that excited him to the point of euphoria: “I follow the golden advice of wine, for wine is sometimes on the scale of dreams.” (Antonio Machado); “I drink wine just as the root of the willow drinks the clear wave of the torrent.” (Omar Khayyam); “What is drinking? A mere pause of thought.” (Lord Byron). He liked a Nahuatl poem very much, but because of its length he never managed to memorize it. In each attempt he would change phrases, words, convinced that he was respecting the original, when what he achieved each time was a meaningless pastiche that killed us with laughter.

The text in question says: “…enter [el vino] “gently, but at last it bites like a snake (…) and then you will be like a man who lies down in the middle of the sea and sleeps on the top of a mast. And at last you will say: They have beaten me and I feel no pain; they have beaten me and I feel nothing; when will I be able to drink again?”

Bonachea died on a Friday from a stroke. He had been experiencing headaches for some time, but he did not pay attention to the signs. Two or three days before the unfortunate event, he passed by my house late at night. We talked about the usual topics, but it was clear that he didn’t want to leave. As we reached the door, he turned around to give me a hug, which was unusual for him.

At that time I was finishing a book of poems. I took the name of the bronze piece to head a text that I dedicated to him, the same one that eventually became the title of the whole collection. That day in Aguas Blancas I read it to myself in his memory.

The figure in the sculpture is carrying a unicorn (the ability to dream?), even though it is missing a wing (lost in so many battles for survival?) and has a hole in its chest, right at the height of the heart (to drain the pain?). But it flies and accompanies it on its journey towards that stage that death cannot devour and that, for lack of another term, we call posterity.

angel with broken wing

for vr Bonachea, there

out of his androgyny

There is no one above the angels

nothing universally established

some peck at the fruits

but others feed

of the insects of light

that they mix with honey

old photographs

and escaped notes

from the lips of miles davis

They don’t announce themselves, much less say goodbye

are or are not on the table to knead the bread

among the children’s toys

trapped in the pages of a book

or happily passing the chalk

squeaky through the blackboard of the eyes

descend the same

on a woman’s body

that move the eternal balances

where the old people without memory

They pretend to dream of happy days

They urinate against mirrors

They congregate by the millions

on the heads of the pins

and they cast compassionate glances at us

while things change places

because the order from here below

can drive them crazy

Ah, the angels who let themselves be seen

only if they lose a wing

which is like saying the desire to fly

and they start to tumble

to give an opinion on everything

to cover our chest

with his terrible cloak