These are the last words I write for the column “with black ink” in OnCuba.

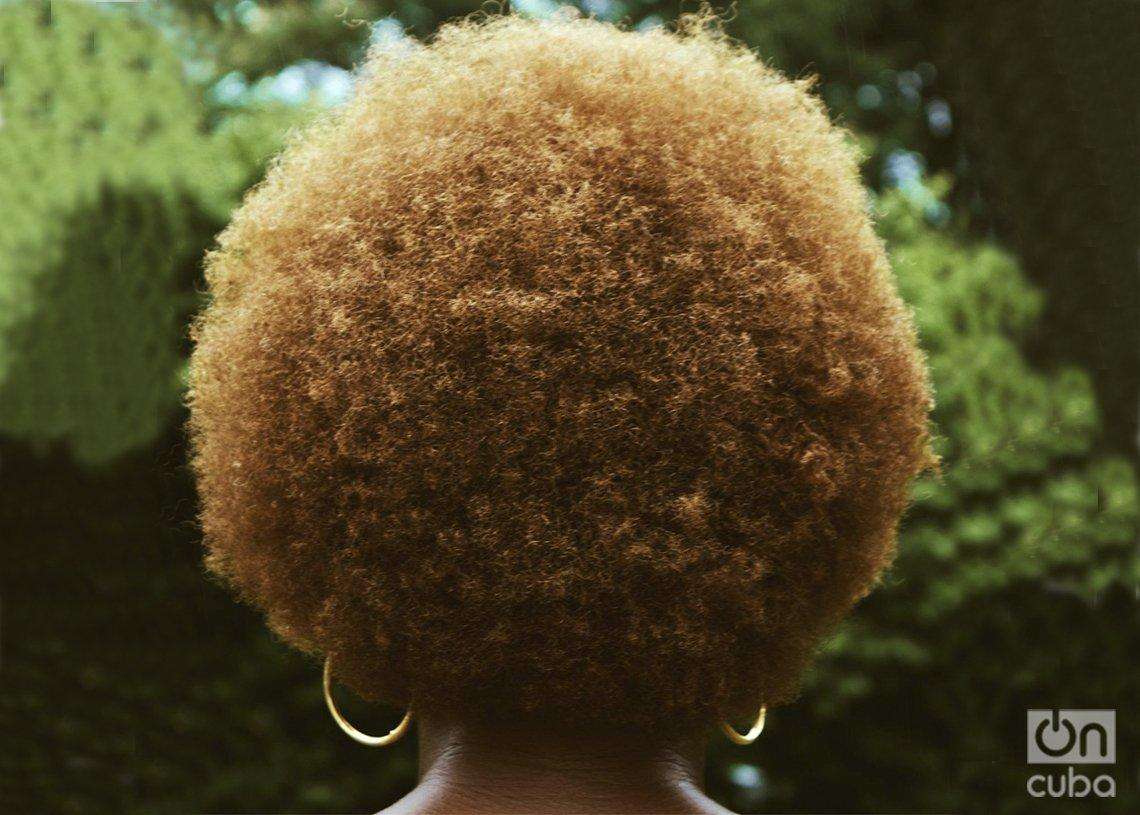

A cycle is closing and, in the same spirit with which I opened it two and a half years ago, I dedicate the last installment to black women: to my mothers, my sisters, the daughters of my sisters; to the near and far maroons, from the fierce warriors of the 19th century, Carlota and Fermina, to my grandmother and my mother, no less tenacious. They are the ones who have stayed this long, twice a month, encouraging me not only to write who we are but also how the world looks from our perspective as black women.

This has been a challenge that I accepted honestly and I have been fulfilling tirelessly, bringing to those who have been kind enough to read me visions of us and from us. I am guided by the determination and obligation to tell ourselves to break with the usual: that it is always others who take the floor for us and pretend to say who we are.

They don’t know us. They have no idea what we think, feel and dream as black women; but this does not stop others from foisting on us inaccurate identities and telling us how we should be: sandungueras or servile, agile athletes, cooks, maids and nannies, dancers and singers. There is nothing wrong with being. But we are much more. A little, just a little, she has revealed “With black ink”. It is necessary to continue. It will be in another format, breathing other airs, in other spaces. But it will be

My black ink does not dry. Black Cuban women, about whom little is known because it is difficult for us to find space for expression, have a lot to tell about us, for us. He leaves “With black ink” from OnCuba, but it does not disappear.

We are survivors, just being here and now to say it is the result of our uninterrupted resistance. It must not be forgotten: being of African descent means coming from people stripped of their humanity, whose forced entry into what is called the West occurs under the condition of merchandise, as work instruments. None of our ancestors—African, indigenous, or European—imagined that we would be here now, be it in Philadelphia or Havana, Reykjavik or Paris, San Salvador de Bahia or Berlin, reclaiming our space, our time, and our existence.

“I’m my ancestor’s wildest dream!”, we write, read, sometimes find printed in black and white, on a sweater. For enslaved Africans and their offspring at some point in our nations’ history were not supposed to become citizens, that we could exercise our agency and power in the civic arena, much less in the political or economic arena. They will not stop trying to prevent us from doing so in the present either; but we persist, because we are survivors.

I have greatly enjoyed the experience. Before leaving this dear space, I am thanking OnCuba the hospitality and the dedicated edition of my texts throughout the thirty months of life of “with black ink” under this format.

But I will always be even more grateful to the readers who, from anywhere in the world, have approached this open window from my black Cuban and diasporic experience. It has been more than two years full of surprises, receiving the comments and affection of many people who are not even Cuban or black or interested in Cuba or in the experience of black women. Only people who come to read and find themselves, or find a calling in what I write.

Even when I’m focused on what’s to come, I can’t stop a bit of sadness from infiltrating me as I feel that I am closing this last installment, this column, this episode. There is no remedy, that’s how goodbyes are. But I shake and, barefoot to better feel my roots, near the water, inside the water, being the water, I smile, always ready for all rebirths.

Thank you, again and again, to all of you, for being there: the best gift that this writer has been able to receive. And don’t get too far away from me because we’ll meet again there; this journey just continues.