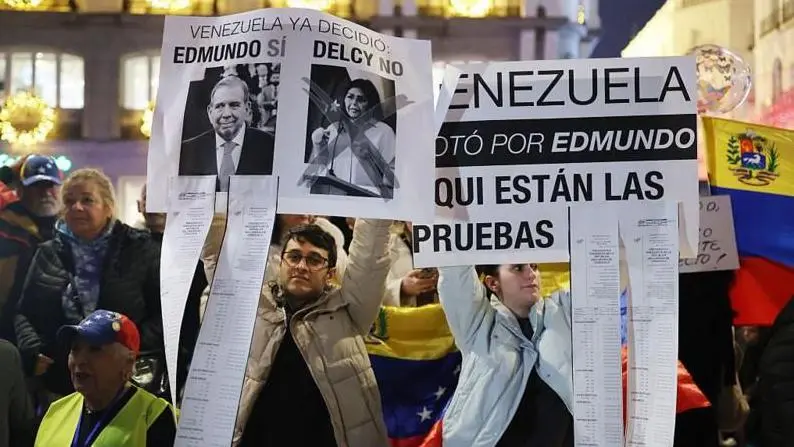

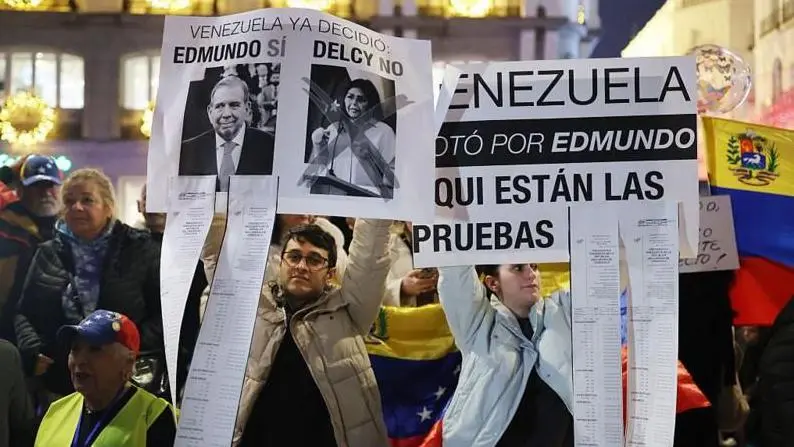

Among the many questions that have arisen since the dramatic events of last weekend in Caracas —and there are many—one of the most persistent centers on the woman who now leads what U.S. officials call Venezuela’s “interim authorities.”

Why Delcy?

What is it about Delcy Rodríguez, daughter of a former Marxist guerrilla and lieutenant of ousted dictator Nicolás Maduro, that caught the attention of the Trump administration?

And why did Washington opt for a declared Chavista revolutionary to keep her in power, instead of backing the opposition leader, María Corina Machado, whose opposition movement won the 2024 presidential elections, according to the evidence she presented?

The answer, according to a former US ambassador to Venezuela, is simple.

“They prioritized stability over democracy,” says Charles Shapiro, who was George W. Bush’s ambassador in Caracas between 2002 and 2004.

“They maintain the dictatorial regime without the dictator. The henchmen are still there.”

“And I think this is very risky.”

But the alternative, which involved radical regime change and backing Machado’s opposition movement, would have entailed other dangers, such as possible infighting among opposition figures and alienation of Venezuelans — perhaps up to 30% — who voted for Maduro.

In his stunning Saturday morning press conference, President Trump surprised many observers by disqualifying Nobel Peace Prize winner Machado, saying she “doesn’t have the respect” of Venezuela, and describing Rodriguez as “nice.”

“I was very surprised to hear of President Trump’s disqualification of María Corina Machado,” said Kevin Whitaker, former deputy chief of mission at the US embassy in Caracas.

“His movement was elected by a massive majority (in the 2024 elections)… So by disqualifying Machado, in effect, he disqualified that entire movement.”

The speed and apparent ease with which Maduro was removed and Rodríguez was installed led some observers to speculate that the former vice president may have participated in the plan.

“I think it’s very telling that we just went for Maduro and the vice president survived,” said former CIA agent Lindsay Moran.

“It’s obvious that there were sources at the highest ranks. My first speculation was that those high-ranking sources were in the vice president’s office, or even the vice president herself.”

But Phil Gunson, a Caracas-based senior analyst at the International Crisis Group (ICG), says the conspiracy theory does not stand up to close scrutiny, given the enormous power still held by Defense Minister General Vladimir Padrino López and hardline Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello, both loyal allies of Maduro.

“Why would she betray Maduro, leaving herself internally defenseless against those who really control the weapons?” Gunson questions.

Rather, the decision to back Rodríguez came after warnings that Machado’s rise to power could generate dangerous levels of instability.

In October, an ICG report warned that “Washington should be wary of regime change.”

“The risks of violence in any post-Maduro scenario should not be minimized,” the report urged, noting that elements of the security forces could launch a guerrilla war against the new authorities.

“We warned people in the administration: This is not going to work,” Gunson says. “There will be violent chaos, it will be their fault and they will have to face it.”

On January 5, the Wall Street Journal reported on the existence of a classified US intelligence analysis that reached the same conclusions and determined that members of the Maduro regime, including Rodríguez, were in a better position to lead a temporary government.

The White House has not commented publicly on the report, but made clear that it plans to work with Rodriguez in the near future.

“This hides a certain pragmatic realism on the part of the Trump administration,” says Henry Ziemer, associate researcher at the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

But the challenges, he says, are just beginning.

“Capturing Maduro was the easy part. The broader reconstruction of Venezuela, the oil, anti-drug and democratic objectives… will take much longer to realize.”

For now, however, Rodriguez appears to be someone the Trump administration believes it can deal with.

“She’s been kind of an economic reformer,” Gunson says. “She is aware of the need for economic openness and is not opposed to the idea of bringing back foreign capital.”

Ziemer agrees that Rodríguez may not find it difficult to follow Washington’s orders when it comes to welcoming US oil companies, offering greater cooperation in the fight against drug trafficking and even reducing Venezuela’s relations with Cuba, China and Russia, especially if this means gradually lifting US sanctions.

“I think he can deliver on that,” he says.

“But if the United States calls for genuine progress toward a democratic transition, that becomes much more difficult.”

At the moment, this does not seem to be among Washington’s priorities.

On January 7, Secretary of State Marco Rubio spoke of a three-stage plan for Venezuela, beginning with stabilizing the country and marketing 30 to 50 million barrels of oil under US supervision.

The plan would lead to what Rubio called “a reconciliation process” that includes amnesties for opposition forces, the release of political prisoners and the reconstruction of civil society.

“The third phase, of course, will be transitional,” he said without giving further details.

Article 233 of the Venezuelan Constitution requires new elections within 30 days of a president being “permanently unavailable,” something that would seem to apply to a situation like Maduro’s, who is in a New York jail awaiting trial.

But in an interview with NBCNews On January 5, President Trump stated that there was no election on the horizon. “First we have to fix the country,” he said. “Elections cannot be held.”

Gunson says Washington’s decision not to opt for near-term regime change might make sense, but the absence of a medium- or long-term perspective is disappointing.

“Trump may be getting something out of this, but Venezuelans are not,” he says. “The common Venezuelan is being harmed as always.”

The Trump administration is touting the prospects of international oil companies reinvesting in Venezuela’s corrupt and moribund oil infrastructure, but Gunson warns that the reality could be more complex.

“No one is going to come here with the tens of billions of dollars that are required to start the recovery process if the government is illegitimate and there is no rule of law,” he says.

When former Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez designated Nicolás Maduro as his successor shortly before his death in 2013, the move was described as Chávez’s “dedazo,” a colloquial term meaning “pointing the finger,” a personal designation that bypasses the normal democratic process.

Ambassador Shapiro sees a parallel with Delcy Rodríguez’s rise to power.

“This is Trump’s finger,” he says.