December 20, 2024, 8:42 PM

December 20, 2024, 8:42 PM

The “cantarito” is a Mexican cocktail that is served in a clay glass, it is made with tequila, grapefruit and lemon and is the flagship product of thousands of bars around the country, but especially here, in Jalisco, in western Mexico.

In the “Cantarito del Güero”, one of these famous bars on the roads near Guadalajara, the second city in the country and capital of Jalisco, I met several groups of Chicano tourists – that is, Americans with Mexican roots – who were singing rancheras. and they wore a charro hat and boots.

“Everyone has in their soul what they have,” Ariana, born in Pasadena, California, told me in perfect Spanish with a subtle Anglo accent.

With her overflowing song in her hand, the Mexican-American added: “We (Chicanos) come here because we connect with the environment, happiness and joy. Because we contact our roots.”

There are tourists in every corner of Mexico, but there are Chicano tourists, above all, here: in the region that is known as “the most Mexican in Mexico” because it is the birthplace of mariachi, tequila and charro; That is to say, the source of an image of Mexicanness known abroad that is very postcard-like, but also reality.

And if not, let Armando Pérez de León, a rancher with a bushy mustache and a black hat who I interviewed in Cocula, a town in the area, say it: “This is the most beautiful city in Mexico because people live very peacefully here (…) Here “We like to milk the cows, the cattle, the horse, it’s what we like, it’s beautiful, because it’s so peaceful in the wide area.”

His thick hands, the prolongation of the penultimate vowel of each word, his hat with a steep brim and his kind and determined masculinity made me think of Armando as a character in a Mexican Golden Cinema film from the 1930s.

In some ways, it is: it is at that time that this charro postcard became popular. Let’s see, then, what is true (and what is not so true) that Guadalajara is the most Mexican city in Mexico.

A definition of “the most Mexican”

First of all, we should differentiate between Guadalajara, the city of 6 million inhabitants that is called the most Mexican, and the rural environment that surrounds it, which is where the cultural elements that underpin the famous stereotype are really located.

Then we would have to define who we are talking about: the peasant of northwestern Mexico, man, macho, which begins in Pancho Villa, passes through Cantinflas and ends in Vicente Fernández. An amalgamation of characters, phenomena and historical times that is reduced to one image: the mustachioed ranchero who gives rise to institutions such as the charro and the mariachi.

The local peasant, the charro, is almost not seen in the city, which is as diverse, cosmopolitan and unequal as any Latin American metropolis. Or you can see them, but in specific areas or stores that sell wide-brimmed hats, carved leather horse saddles, and pointed leather high-heeled boots.

In the center of Guadalajara there is a Plaza de los Mariachis, which has two sculptures in reference to the musicians. And little else.

In Cocula, however, 60 kilometers away, rancheros and rancheras are the norm, decorating the street with a sea of large-brimmed hats.

There is also a Mariachi Museum, which tells the story of the origin of a genre that emerged at wedding parties, in marriagesthat Mexicans of peasant origin served for American families in this area that, despite being 1,000 kilometers from the border, seems close.

Jalisco is the second state in Mexico with the most Mexicans in the United States —there are at least 3 million Jalisco residents, according to official figures—and it is the third with the most American residents, despite the fact that it is not close to the border.

Ajijic, for example, is a town in the area at the foot of the beautiful Lake Chapala. And it is, as they would say here, “full of gringos.” Restaurant signs are in English; they receive dollars.

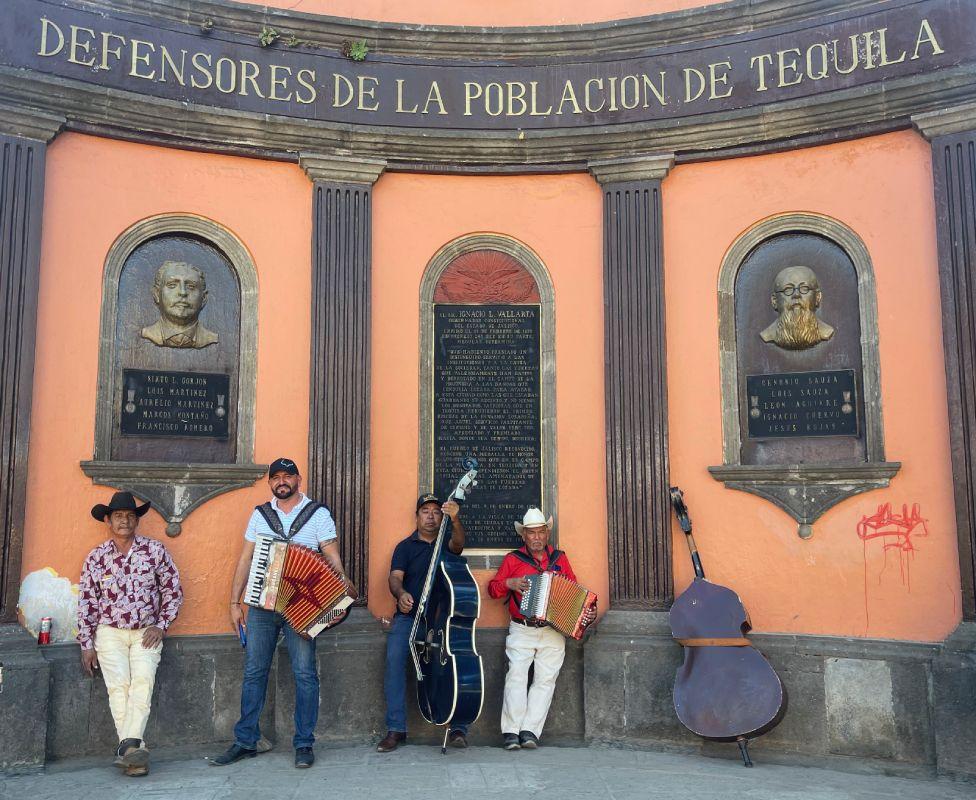

Another of those magical towns in Jalisco is Tequila, a colorful colonial village dedicated to distillery tourism, the large mansions that receive dozens of people interested in knowing how the agave, a succulent with thick leaves and woody thorns, is converted into a smoky and crystalline drink with between 35 and 45% alcohol.

“This rural culture was adopted by Guadalajara, and Mexico in general, as if there had been a marketing campaign according to which we are that“says Antonio Ortuño, a renowned writer from Guadalajara (the name of the city).

And he adds: “This has never been a city full of mariachis, much less charros, and they drink tequila like anywhere in Mexico. So, it was a decision about what our identity is, and many traditional landowner families ended up leaving. identifying with that and it was what was portrayed in the ranchero comedy and tragedy of Mexican cinema.

The idea that the Mexican is a rancher with a mustache was consolidated in the 1930s, when Mexican cinema, partly emerging from Guadalajara, met the demand of a Hollywood in crisis and Mexico, after a social revolution, was in the process of defining the traits of his identity.

Actors like Jorge Negrete and Pedro Infante —and musicians like Vicente Fernández, who has a ranch on the outskirts of the city with a statue and canvas for the charrería— forged this image of the Mexican who, even if he was part of a campaign, exists: in these towns the ranchera plays on the loudspeaker in the central square, there are schools for mariachi children and the men with hats and mustaches, like the actors of the 30s, wander the streets with mystical parsimony, professing a certain idealism for work and romantic love

“Look, I’m going to tell you something,” warned me J. Reyes González, an 80-year-old rancher who was enjoying the morning with his partner to the sound of a ranchera that was playing on his cell phone. “This is a humble little town, where almost all the people work for half food and half income.”

His girlfriend, Adela, added: “He’s an original rancher, he’s not a pirate“.

And then he: “If I tell you that she stole from me, you don’t believe it, she took me to Guadalajaara, you don’t believe it.”

Once again I felt like I was talking to a Pedro Infante character.

What is not the most Mexican region?

But if the postcard of the mustachioed Mexican exists, there is at least another postcard of the Mexican that is almost not seen here: the indigenous one, that of colorful crafts, spiritual rituals and ancestral medicine.

According to the last census, Jalisco is today the state with the least indigenous presence in a country where one in four people declare themselves descendants of indigenous people.

“The rancher turns his back on indigenous Mexico,” Luis Vicente de Aguinaga, a poet and literature professor, told me. “And that distinguishes Jalisco, not only culturally but brutally and violently, from indigenous rural Mexico.”

This region was not part of the space governed by the Aztec Empire. The indigenous groups that the Spanish encountered were small, diverse, some semi-nomadic. And the conqueror, Nuño de Guzmán, was more bloodthirsty and less open to dialogue than his counterpart in the center of the country, Hernán Cortés.

The ranchero, in fact, is whiter and more Creole than the Mexican from the center to the south, who is brown and mestizo.

Almost at the same time that the image of the ranchero became popular, a movement of artists specialized in murals emerged that had a profound impact on the idea of Mexicanness.

“The muralists, with everything and the controversy they have, included almost all Mexicans in the narrative of the nation. And that narrative continues, and goes through (the film) Coco, goes through Pedro Páramo’s film, goes through Frida in a t-shirt: they are national postcards that change and are exaggerated, but they are also handles of identity,” says Verónica López, a renowned cultural journalist from Guadalajara.

So: Jalisco is the most Mexican region, but it depends on which Mexico you want to highlight. Because there are a few.

Things outside the postcard

And one that has recently made an impact on the world is the Mexico of drug trafficking, which beyond violence and illegality, has also been a cultural, urban and musical phenomenon that has fueled identity.

“This is also the most Mexican city to the extent that it was the first city where drug traffickers went to invest their money,” says Ortuño, who begins one of his books, “Olinka”, with one of the key facts about Guadalajara: Half of the illegal money laundering carried out in the world occurs here, according to data from the United States Department of State.

Guadalajara was the largest city in the area where drug trafficking emerged, northern Mexico, and the political power of the institutions and parties here was less than in the center of the country, which created space for an emerging elite.

Part of the city’s recent development, evident in the impressive skyline of modern buildings in the northwestern area, was financed with money from drug trafficking: this is what the Guadalajara themselves say, who identify the area as “the buchona Guadalajara”, in reference to drug aesthetics and ways.

And that is an inevitable part of the city’s current identity.

To which other things are added: a succulent gastronomy that gave the country—and the world—institutions such as the drowned cake, pozole and birria; an International Book Fair that brings together a million readers, writers and editors a year; and a current of counterculture that, among other things, makes the city a museum of modern architecture and a national nucleus of the LGBTI movement.

Guadalajara is, like any large city, many things. It is all that, and it is also—with its omissions—the most Mexican city in Mexico.

Subscribe here to our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

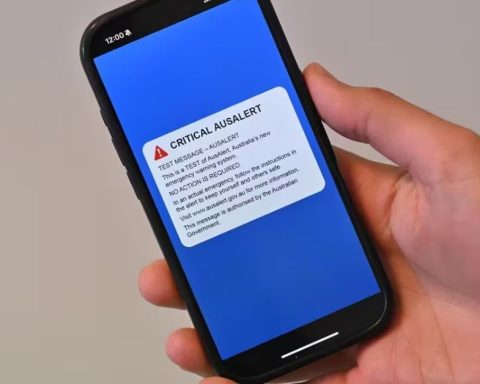

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.