MONTANA, United States. — Before an esteemed reader pulls out the gun by shooting me an email, I will make it clear that this is not an anti-immigrant column. I have published several immigration defenses. See, for example, Migration as an individual right Y The ethical case for migration. My purpose now is to explore the attitudes that differentiate economic immigrants and political exiles. I do so with the caveat that this is a blurry distinction when applied to those leaving countries that exercise enveloping control over both political and economic domains.

The title “Why I’m Not An Immigrant” is a deliberate paraphrase of a classic article by economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek titled “Why I’m Not A Conservative.” In that work, Hayek seeks to explain how his classical liberalism differs from conservatism. He pointed out that, despite its similarities to conservatism, his belief in freedom implied a forward-looking attitude. His liberalism was not based on a conservative nostalgia for the past or a romantic admiration for what he had been. He explained that while liberalism was not adverse to evolution, the fundamental trait of conservatism was fear of change.

Likewise, economic emigration and political exile share many characteristics, but they are differentiated primarily by the action of return. The return separates economic immigrants from political exiles. Neither economic migration nor political exile are actions that, in themselves, ennoble or degrade. Neither defines life, but economic migration and political exile frame our experiences in life differently.

Both economic immigrants and political exiles dream of a romantic return or visit to their homeland. However, those who emigrate for economic reasons aspire to return when their personal economic situation allows it, perhaps in the golden years. By contrast, political exiles are not prepared to return as long as the oppressive conditions that prompted their exodus are present.

For exiles, returning is not an option guided by personal reasons or conditions, but rather an action focused on the conditions that affect their compatriots. Going into exile is a political statement against a collective injustice. When a political exile succumbs to the personal melancholy of him returning without a fundamental change in the conditions that led him to exile, he renounces his status as a political exile and becomes an immigrant.

This is not a critical judgment, but a definition. Sometimes returning is imperative for some Cuban exiles who, after decades of courageous opposition to oppression, decide to visit their homeland. Many motivated by humanitarian reasons; share once more, perhaps the last time, in the company of loved ones, or bring relief to someone in need. Consequently, the Cuban community has changed, to some extent, from a community of political exiles to one of immigrants.

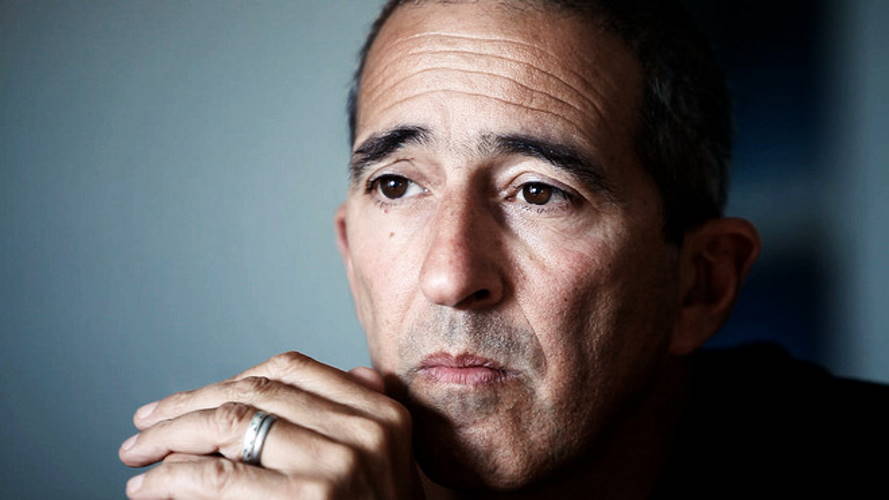

I left Cuba in 1961, at the age of 13, without my parents, as part of Operation Pedro Pan, and I began life in the United States with an indelible, albeit juvenile, idea of our individual liberties. I swore I would not return until Cuba was free again. Thus, I have never returned to my country of birth nor have I been able to visit the grave of my parents in the Colón Cemetery in Havana. That is why I am not an immigrant.

In the initial days of exile, in addition to delivering newspapers, working as a dishwasher, a waiter, and more, I also worked as a farm worker picking tomatoes. Backbreaking work where the pay was 15 cents per basket of tomatoes picked. It was an experience that framed my life. For many years I mentally calculated all my purchases in terms of baskets of tomatoes. A $10 purchase meant about 67 baskets of tomatoes, more than two days of work.

Renowned columnist Charles Krauthammer, who began his professional life as a psychiatrist, acknowledged his early experiences by referring to himself as “a psychiatrist in remission.” Life has been good to me, and I no longer calculate my purchases in terms of baskets of tomatoes. And, like Hayek, I am not nostalgic for the past. Therefore, I define myself as “recessed exile”.

Note: Dr Azel’s latest book is “Freedom for Newbies”.

Receive information from CubaNet on your cell phone through WhatsApp. Send us a message with the word “CUBA” on the phone +525545038831, You can also subscribe to our electronic newsletter by giving click here.