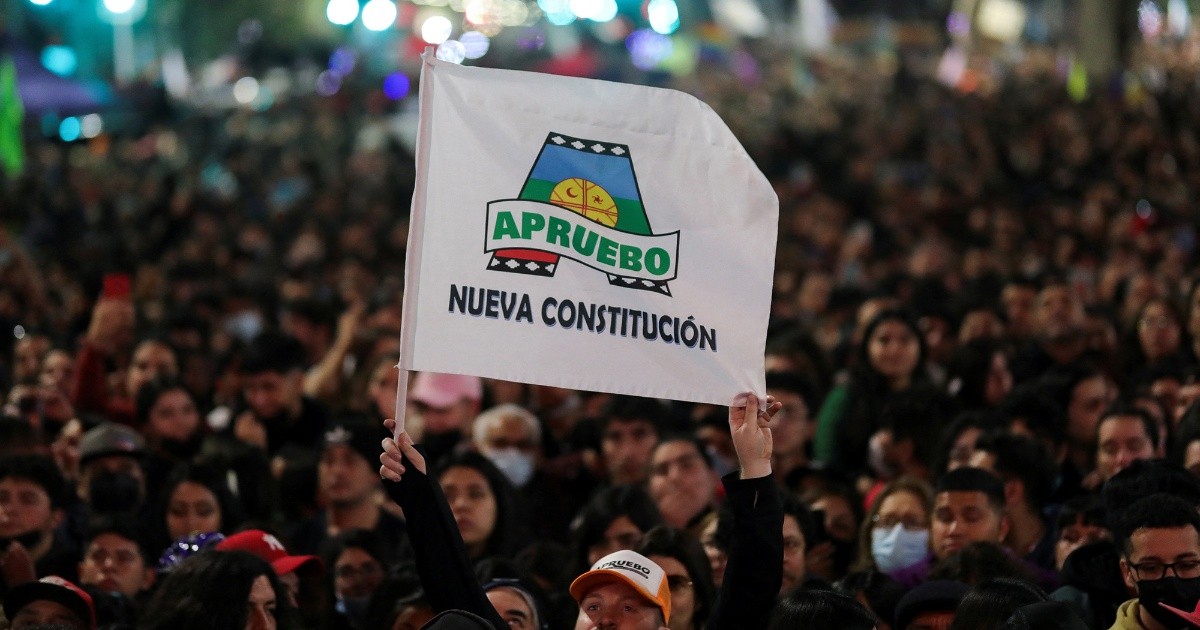

Implementing a new Constitution or starting the drafting of another project are the scenarios that will open in Chile after the result of the constitutional plebiscite this Sunday.

Chileans are called to the polls to “Approve” or “Reject” the text that for a year elaborated a constitutional convention, to replace the one in force since the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990).

According to surveys, rejection is the option in advantage. But whatever the result, a broad political and citizen consensus, say polls, is inclined to start a new reform process on Sunday night and different “road maps” have been drawn up.

“There is a consensus that the 1980 Constitution is no more and that we would move on to another that is the result of a democratic process that also has advanced areas for the establishment of social, political and economic rights,” said Cecilia Osorio, an academic from the Faculty of Government of the University of Chile.

If you win approval

The law that regulated the constitutional process in Chile indicates that if it wins “approval”, the new Constitution will become effective 10 days after the plebiscite. If it is rejected, the current text is kept.

The new Constitution repeals the 1980 Constitution, which is considered the basis of a model that allowed decades of stability and economic growth, but with a profoundly unequal society.

The proposed text ends with the State that favors private initiative and implements a “Social State of Rights”.

It will also define Chile as a multinational state that recognizes the autonomy of indigenous peoples. It incorporates a parity democracy, with 50% of women in state positions, it will also allow the interruption of pregnancy and will recognize sexual diversity.

To implement it, 57 transitory norms will be activated, while all the rights and norms of the new Constitution will be subject to the elaboration of laws in Congress.

The implementation deadlines extend until October 2028.

Aware that the approved text can also be reformed, supporters of “Approbation” have also opened up to “analyzing” changes to the constitutional text in Congress.

For Marisol Peña, an academic at the Center for Constitutional Justice of the Universidad del Desarrollo, these political commitments seek to introduce modifications to the new Constitution “so that it is more realistic, more viable and better interprets Chileans.”

Triumph of rejection

If the rejection is won, President Gabriel Boric announced that he will call to start from “zero”, with the election of a new Convention and the complete drafting of a new text.

According to Boric, the plebiscite that enabled this first constitutional process, in which 78% of Chileans approved reforming the Magna Carta, ended up definitively burying Pinochet’s Constitution.

An eventual proposal for a new Constitution must, however, go through Congress, currently tied in political forces, where there is no agreement on the terms of another constitutional process or conditions that were very popular among citizens, such as the inclusion of parity of genders and indigenous seats, something that at the moment more conservative leaders are not willing to consider.

Under the slogan “reject to reform”, supporters of this option promised to advance amendments to the current Magna Carta. To do this, they promoted a law in Congress that lowers the quorum in order to modify it.

“They took up many issues that the draft constitution reveals, but what they have proposed is like a list of intentions that it is not clear how they are going to articulate it. In addition, in its historical trajectory, the Chilean right has not been available to reform the Constitution Osorio said.

But there are other groups in favor of rejection that seek the drafting of a new Constitution and have called for “a (new) one that unites us.”