October 24, 2024, 6:53 AM

October 24, 2024, 6:53 AM

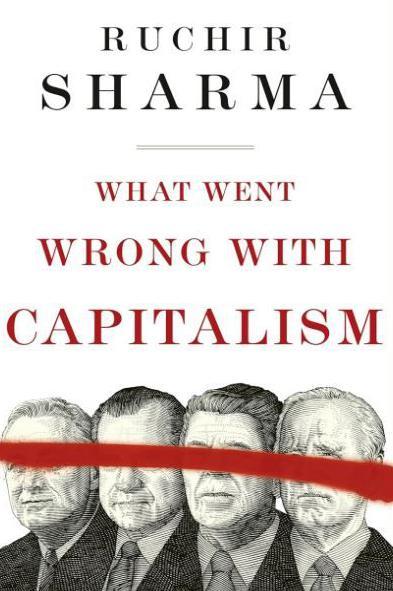

“What went wrong with capitalism?” That is the question and the title of the new book by analyst and investor Ruchir Sharma, a banker who has spent almost his entire career on Wall Street.

After growing up in India and Singapore, he worked for some of the biggest names in New York’s Financial District, an experience he says gave him an ideal vantage point to watch how money flows through the global economy.

Your conclusion? Today’s capitalism is not reaching its true potential.

Author of successful books such as “The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World” or “Emerging Nations: In Search of the Next Economic Miracles”, Sharma is president of Rockefeller Capital Management, founder and director of Breakout Capital investments.

Vivienne Nunis, a journalist for the BBC’s Business Daily radio programme, sat down with the author in London to delve into some of those criticisms.

What follows is an adaptation made from the radio program.

“This book is a revisionist history of capitalism,” says Sharma in dialogue with the BBC.

And part of the interest in writing about this topic is related to his personal history.

The banker grew up in India in the 70s and 80s, whose nature was “very socialist,” recalls the author, including measures such as the nationalization of banks.

In that context, “I grew up aspiring to be a capitalist.”

Sharma went to live with his family in Singapore, where he was impressed by the economic freedom and “prosperity,” in contrast to what he had seen in his home country.

That contrast directly influenced his view of the world.

His next destination was the United States, the largest economy in the world.

Working in the bowels of capital, Sharma began to wonder why in Western countries so many young people say they would prefer to live in socialism, and to reflect on what has gone wrong in the capitalist system, to the point that many have become skeptical.

In “What went wrong with capitalism?” argues that part of the blame lies with the gigantic spending incurred by governments, addicted to debt, and central banks, by stimulating the economy by injecting money into the system, instead of letting market forces restore balance.

At the same time, he points out, “in recent decades there has been a perversion of capitalism. The people who are benefiting from capitalism should not be the big beneficiaries,” he says.

“Something is wrong when you see that the people who have prospered the most in the last 20 years are the same people who have great access to financing,” he adds. “There has been an explosion of billionaires.”

Today, the United States is home to more than 800 billionaires (collectively, their wealth amounts to nearly $6 trillion, according to Forbes), more than double what it was before the pandemic.

But Ruchir Sharma says that while billionaires are an obvious target for critics of growing inequality, there is a more hidden culprit: decline in productivity growth.

If companies produce more, he says, the economic pie can grow for everyone, allowing companies to raise wages without causing inflation.

And although in the past weak companies were allowed to fail, in recent decades, he says, The so-called “zombie companies” were kept alive thanks to central banks determined to keep interest rates low, as was the case throughout the 2010s.

Furthermore, the expert maintains, troubled commercial banks, considered too big to fail, have been propped up by government bailouts, a policy with which he disagrees.

“The Roaring 20s”

But it wasn’t always like this. There was a time when such actions were considered detrimental to the way capitalism should function.

Reviewing American history, Sharma reaches back to the 1920s, a time many associate with a glamorous age of jazz, social liberation, and rising prosperity.

However, at the beginning of that decade there was a deep economic crisis. known as The Depression of 1920-1921which occurred after the end of the First World War, which lasted relatively short, but was very painful.

The analyst argues that important lessons can be learned about the “hands off” policy applied at that time. Lessons, he adds, that have often been forgotten.

What happened in those years? Why was the anti-intervention policy so good according to him?

U.S. government spending and borrowing had skyrocketed during World War I.

Then, as the economy tried to adapt to peacetime, people rushed to buy goods that had previously been rationed and inflation escalated.

Meanwhile, troops returning home quickly swelled the ranks of those looking for work.

As the recession took hold, prices fell and business activity collapsed, but the Federal Reserve insisted on raising rates.

Some 500 national banks failed in 1921, as industrial production plummeted and unemployment doubled.

That might sound devastating, but Sharma says that hands-off approach—letting the crisis run its course, without pumping money into the economy, increasing public debt, or bailing out the banks—worked.

That approach allowed those with weak performance to be eliminated from the economy and the crisis ended in just 18 months, argues.

“We had incredible prosperity after the non-intervention period,” he notes. “People learned the lesson that if you don’t intervene, the weak will be marginalized.”

And today?

Unlike what happened at that time, in more recent years, the responses of governments and central banks to economic crises in the world have been very different.

There is the example of the Great Crisis of 2008, when large banks were rescued.

In that crisis, “the economic recovery was weak. Many economists thought the lesson was that we should have done more,” says Sharma.

A few years later, during the 2020 pandemic, in the midst of a brutal human and economic crisis, once again the authorities intervened by injecting large amounts of money.

“Governments announced major lockdowns and administered stimulus. The idea was that it was better to make mistakes through excess than through lack of action,” says the author, although he warns that it is not about doing nothing either.

“Yes, governments must intervene in crises. But this time the stimulus was so massive that it caused inflation and also asset prices to rise.”

What he opposes, he points out, is excess state and monetary intervention.

He comments that until the 1970s, the authorities were reluctant to intervene in the economy. In those years, “they were not supposed to rescue the private sector”

The problem is that now “There is a culture of rescue,” he says.

Intervene in times of crisis

On the other side of the scale, There are many economists who defend economic interventions in times of crisis.

One of them is Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, who led the rescue of the investment bank Bear Sterns in early 2008.

“I was worried, but I felt very comfortable with the decision,” Bernanke said on the BBC program Marketplacewhen a decade had passed since the rescue.

“If Bear Stearns had failed uncontrollably, that would have reverberated through the financial system, causing a lot of damage.”

Soon after, other investment banks were on the brink and Alistair Darling, then Chancellor of the Exchequer in the United Kingdom, intervened with the largest bank rescue in British history.

“Of course it’s scary, it was like a catastrophe knocking on the door, but it took me a nano second to think that we couldn’t let that happen.”

Who is right then? Should policymakers intervene and support private companies to stem the damage when disaster strikes, or should they accept short-term suffering for future productivity gains?

It is an issue that is unlikely to be resolved soon.

For now, Ruchir Sharma says some plans should be outlined, before the next crisis hits.

“Let’s draw the lines now,” he says, so that governments have a roadmap in the event of a financial crisis.

“Let’s make a plan today,” he says. “I don’t feel like we’re designing them.”

Subscribe here to our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.