February 17, 2023, 2:20 PM

February 17, 2023, 2:20 PM

“Total income to date, excluding our latest undistributed dividend, has been approximately £1.5 million in Swiss Francs and Venezuelan Bolivars, which we convert our income into, as they remain the hardest currencies in the world.” .

The phrase appears in Ian Fleming’s novel Thunderball (Thunderball), belonging to the James Bond agent saga, and is pronounced by the leader of the Specter criminal organization, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, while taking stock of the profits left by his misdeeds.

The reference that the novel makes to the iconic 007 of the bolivar may seem crazy today, given that in barely fifteen years the Venezuelan currency has undergone three reconversions, in which 14 zeros were removed. However, it illustrates the reputation enjoyed worldwide by the Venezuelan currency in the mid-20th century.

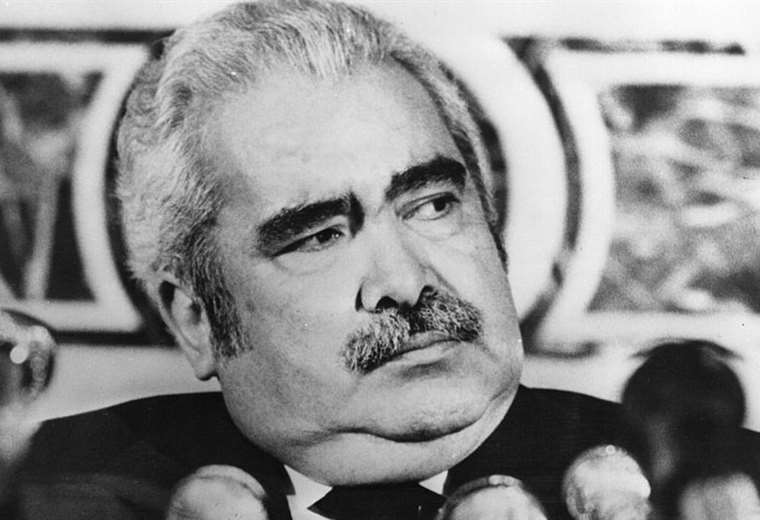

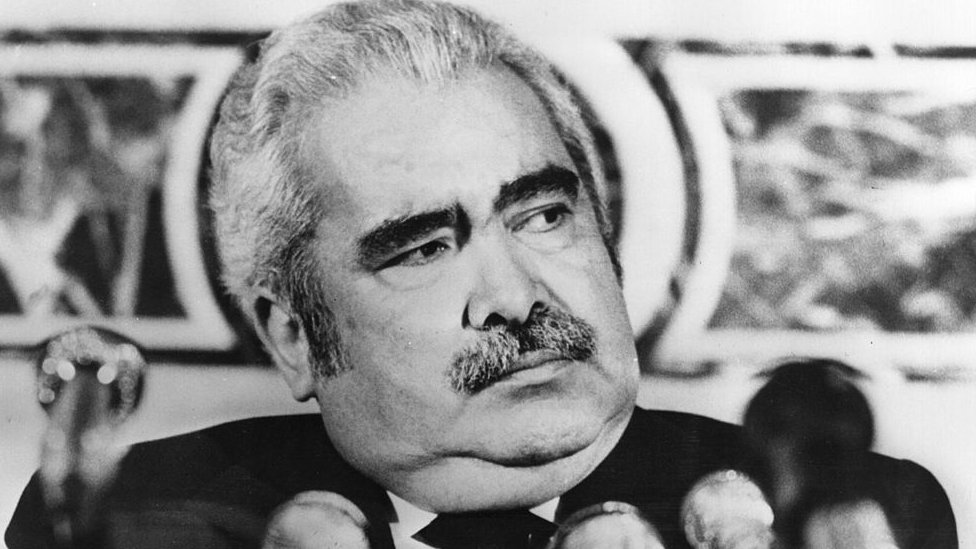

That fame disappeared on February 18, 1983. It was the last day of the working week and, therefore, went down in history with the gloomy name of “Black Friday”. That day the government of then President Luis Herrera Campins (1925-2007) announced a drastic devaluation of the bolivar.

“Since the 1930s, the bolivar was one of the most solid currencies in the world and a symbol of Venezuelan prosperity,” historian Tomás Straka tells BBC Mundo.

A prosperity that attracted immigrants to an oil country that was developing and offered great opportunities.

“The bolivar was a symbol of what made Venezuela a reference country in the 20th century: the country of social ascent, of great infrastructure works, the country that attracted immigrants from all sides, that defeated malaria and almost liquidated to illiteracy. That Venezuela vanished like a mirage on Black Friday“Added the member of the Academy of History of Venezuela.

40 years after the measure, we analyze the factors that led to Black Friday and how four decades later its effects are still present.

the dream is over

“Black Friday meant the rupture of the period of greatest exchange and monetary stability that any Latin American country had,” says José Guerra, an economics professor at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV).

Along the same lines, the political scientist and consultant Fernando Spiritto pointed out in an article that on February 18, 1983 “the culmination of a long cycle of economic stability that began in the early 1960s and which, with very notable exceptions, was characterized by high growth and low inflation”.

Until that day the bolivar maintained a fixed parity of 4.3 for every US dollar that lasted a decade.

From there, currency control was imposed with three exchange rates, through which the government awarded foreign currencies to citizens and companies at a certain price, according to the use they were going to give them.

The devaluation impoverished, overnight, wage earners, retirees and everyone who had their savings in bolivars, who lost 70% of its value.

The measure also caused a disappearance of products, due to the increase in imports.

“I was a child, but I remember that suddenly there were no apples in supermarkets or that the variety of toys was reduced,” adds political scientist Guillermo Tell Aveledo, to illustrate the changes that occurred in the country that until then was experiencing a boom of consumption during which the famous phrase of “ta’ cheap, give me two” and the term of “Saudi Venezuela”.

Likewise, it meant that those who had become accustomed to traveling abroad, especially to Miami (United States), to vacation or go shopping, could no longer do so with the same frequency.

In the early 1980s, some 400,000 Venezuelans (3% of the population at the time) went to South Florida annually, according to official estimates at the time.

The devaluation showed that the growth recorded in previous years was sustained by public spending, which promoted an economy of ports, based on the importation of goods. And that the millionaire investments destined to diversify the productive apparatus had not achieved their objective.

The seed of Black Friday

Herrera Campins’ decision had been expected almost since he arrived at the Miraflores presidential palace in March 1979.

“I have to receive an unbalanced economy and with signs of serious structural imbalances and inflationary and speculative pressures that have alarmingly eroded the purchasing power of the middle classes and innumerable marginal nuclei. I receive a mortgaged Venezuela!”, was the alarming diagnosis that the Social Christian ruler did when he received the presidential sash.

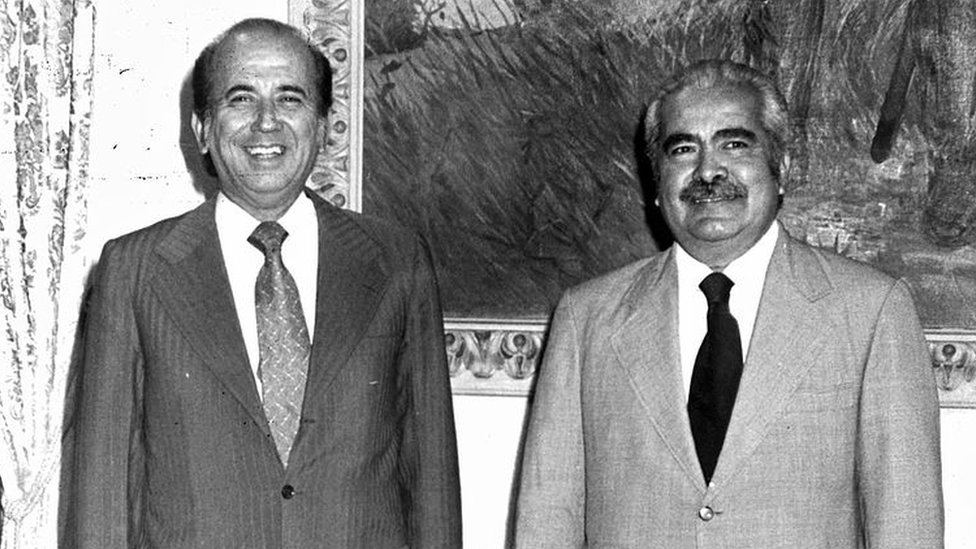

For the economist José Guerra, who was also director of Investigations of the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV) and deputy of the National Assembly, the seed of Black Friday was sown in the previous government, led by the social democrat Carlos Andrés Pérez (1974-1979). ).

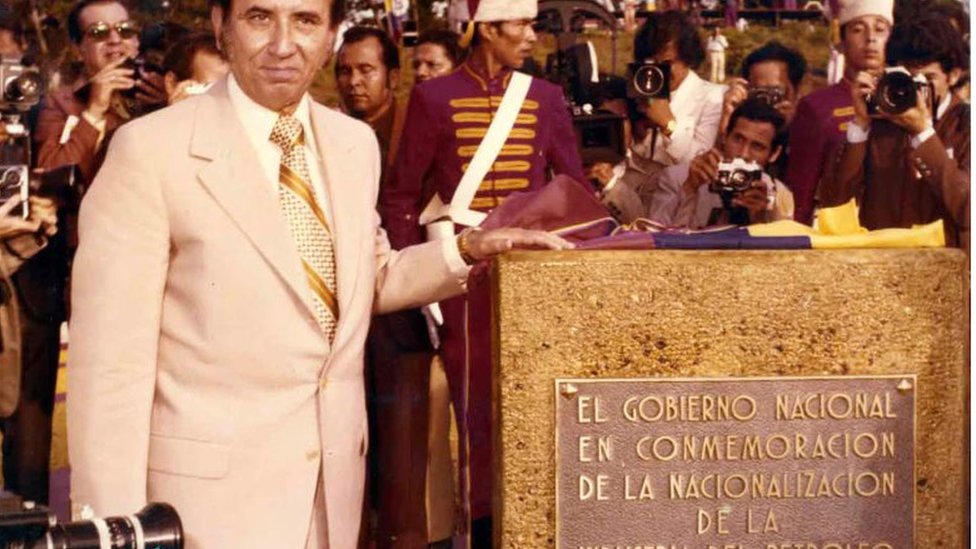

In 1976 Pérez ordered the oil nationalizationwhich meant an injection of resources for the State.

Through his project “Great Venezuela”, large infrastructures and huge state industrial complexes were built, some poorly planned and managed; and the bureaucratic apparatus and the granting of subsidies to basic goods were increased.

This movement occurs in a context of high oil prices, mainly due to the Yom Kippur war, which pitted Egypt and Syria against Israel in 1973 and which caused the oil embargo from Arab countries to the West for its support of Israel.

Years later there was a second oil crisis that impacted prices, with the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979 and the start of the war between Iraq and Iran in 1980.

“Starting in 1976, a very large expansion program began, thanks to the sudden wealth received from the rise in oil prices, which doubled due to the Arab embargo on the West,” explains Guerra.

“The State began to grow, but when oil prices fell, external debt was resorted to to maintain the rate of spending. In Pérez’s five-year foreign debt tripled. And a very compromised fiscal situation was generated,” he added.

For Spiritto there was a miscalculation: “The external debt grew because the economic authorities of the Pérez government thought that oil prices would rise for a long period.”

However, the days of fat cows did not continue and by 1981 crude oil was trading downward.

Herrera Campins tried to correct the course and the central government began to reduce public spending during the years 1979 and 1980.

However, the inflation and social unrest caused by the adjustment they stopped the rulerwho did not have a majority in Congress or the support of the unions, the business community, much less the citizens to continue with his reforms.

“People wanted to spend, nobody wanted to hear the word austerity and that was because they believed that the economy would continue to grow despite everything,” Aveledo explained.

Although he agreed that Venezuelan society at the time was not inclined to reform the economic model dependent on oil income, the historian Straka criticized the actions of the authorities.

“The government took advantage of the oil bonanza caused by the Islamic Revolution in Iran and the subsequent war between that country and Iraq to apply what is popularly known as ‘running the wrinkle’. It stopped the reforms and opted to keep the bolivar overvalued to facilitate the importing goods and generating a fictitious sense of well-being, but when oil fell again the government had to apply electroshock“, he narrated.

external causes

Although the errors and mismanagement of the Venezuelan governments caused the debacle of the bolivar, the three experts affirmed that there were external factors that also had an impact on the crisis.

“The decision of the United States Federal Reserve to raise interest rates to 20% caused an outflow of capital from the entire region, including Venezuela, that was looking for better returns, and raised the cost of debt. And to top it off in August 1982 Mexico declared itself insolvent and caused all Latin American debt to be characterized as dangerous and credit lines to be closed,” Aveledo listed.

It is estimated that months before the imposition of currency controls Venezuelans took out of the country about US$ 8,000 million. The BCV reserves, for their part, went from 19,069 million in 1981 to barely 4,000 million in February 1983.

And to top off that year, Venezuela had to pay US$ 16,000 million for external debt, which was equivalent to 82% of oil exports of that year.

“This monumental outflow of capital made the BCV unable to maintain the exchange rate,” added Guerra.

“Something traumatic”

Black Friday has been engraved in the psyche of Venezuelans. This, despite the fact that from the economic point of view other events such as the financial crisis of 1994, in which half of the banks operating in the country disappeared; or the hyperinflation of recent years have been worse.

For Guerra, this happens “because you came from decades of stability, from having the highest wages, the lowest inflation and the highest growth in Latin America. It was something traumatic.”

“Saudi Venezuela ended that day”add.

But the bolivar was not the only one that lost on that fateful day in February, since the Venezuelan political system that was established after the fall of General Marcos Pérez Jiménez, on January 23, 1958, was also hurt.

“Black Friday broke democracy,” Aveledo declared.

For his part, Straka delved into the matter saying: “Venezuelan democracy was popular because society felt that it lived better with it.”

“The passage of Pérez Jiménez to democracy meant for many Venezuelans having running water, electricity or wearing shoes. That social ascent ended in the 80s (…) In 1979, 60% of Venezuelans could be considered middle class, but in 1999 only 30% were. A process of impoverishment so great that it does not affect a political regime is not possible, especially when that regime is based on the promise that you will live better, “he concluded.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC News World. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.