It is frequently asserted that the public opinion battle over the Russian invasion is being won by Ukraine. And it is true. The President Zelensky He has shown a very distinctive style of communication and a very good ability to impose his narrative on the media.

However, when making this assessment, we usually look at who wins this communicative battle in the global north. Could something different be happening in Russia?

Opinions favorable to Putin

There are Russian public opinion research organizations that are part of the Russian state, such as the Russian Center for Public Opinion Research (VCIOM) and the Public Opinion Fund (FOM). As might be expected, the results of your measurements are usually very favorable to Putin.

“In your opinion, is President V. Putin doing his job well or badly?” is a classic question of both questionnaires. The result for the last published poll is 71% for the “fairly well” option, with a 7-point increase in the week of the invasion compared to the previous week.

“Do you prefer to trust or distrust Putin?” is another question. In it, the “trust” option reaches 50% (it grows 13 points compared to the week before the invasion), while “distrust” obtains 30% (it falls 15 points).

There are also specific questions about the war between Russia and Ukraine. “On February 24, Vladimir Putin announced the start of a military operation in Ukraine. Do you think the decision to carry out a military operation was correct or incorrect? On the most recent WCIOM survey 68% answered that it is correct, 22% that it is incorrect and 10% stated that they did not have enough information to give an opinion.

This question offers a first clear warning about the measurement: speaking of “military operation” as a euphemism for war offers an important bias in the questionnaire.

When the results are induced

Polls are highly sensitive public opinion measurement instruments that can be affected by many variables. One of them is the questionnaire. Any pollster, even using fairly serious and orthodox methods, can affect the results so that they favor an answer. That is, it is technically possible to induce results with political or other justification.

There are two types of bias that the questionnaire can induce, deliberately or inadvertently: the first is of a semantic nature – the construction of the questions, the words used and their exact phrasing – and the second is that of the sequence (related to the logic that follows questionnaire).

When a questionnaire inquires first about sympathy for Putin and then about the level of agreement on the “military operation”, it sends the interviewee another bias. This time it also serves as a warning signal about the possible origin of the survey.

A third important bias can come from the survey method. Both state measurement centers work with telephone surveys. Receiving a call home or mobile inquiring about one’s sympathies for Putin can immediately activate the respondent’s self-preservation instinct.

German public opinion researcher Elizabeth Noelle Nauman He affirmed that we all have a quasi-statistical sensory organ that allows us to gauge the state of public opinion and what the majority opinions are. Noelle-Naummann identified the “silent minorities”: when we feel we are in a minority, we are more likely to keep quiet about our true political preferences.

In an authoritarian regime, this response is not a trivial reaction of hypersensitivity, but rather a protective mechanism in the face of a situation that may present very real risks.

Pro-war consensus in doubt

Even so, the two pollsters closest to Putin mentioned above throw up some interesting data that cast doubt on the majority consensus in favor of war.

sociologist Alexey Bessudnov underlines the existence of gender, age and urban/rural gaps. Young people are less likely to support the military operation. Among people over 70, nine out of 10 support the “special military operation.” Among those under 30, about half say they are against it, while part of the other half say they “don’t know” how to answer the question. Women say they do not support the “military operation” more often than men.

meduza.io

On the other hand, anti-invasion attitudes are more pronounced in Moscow and Saint Petersburg than in the less urban areas of Russia.

Another important element, also related to age, is that Russian viewers approve of the “military operation” and support is significantly higher among those who watch television on a daily basis. It is not only that television is dedicated to propaganda, but that those who watch it already agree with the content of the programs on social or political issues. It is difficult to discern where is the cause and where is the effect in this relationship. As in many other societies on the planet, it happens that among those over 45 years of age, the majority watch television every day, while among young people hardly anyone does.

Public opinion in authoritarian regimes

It is clear that public opinion research on political issues in authoritarian regimes has a different logic than surveys in free and democratic societies.

the iranian professor Ammar Maleki of Tilburg University, points out that the Iranians (and possibly the Russians) do not report honestly about their sources of information when the anonymity of the survey is not guaranteed. 40% of Iranians said they watch TV channels satellite in an online survey, compared to 5% who said the same in a telephone survey.

The Nicaraguan presidential election of 1990, when Violeta Chamorro snatched the presidency from Daniel Ortega, aroused enormous interest in the world, and for this reason it was one of the most measured electoral processes. At least 17 pollsters, among the most prestigious in the region and in the US, wanted to predict the results. Only two pollsters were right in glimpsing Chamorro’s triumph, and they were not among the best known.

An important differentiating element was the pencil with which the interviewer noted the responses of the interviewee. Most of them did it with red and black pencils, which were the only ones available in the Nicaraguan market at the time (a not very subtle way in which the Sandinista revolution wanted to enter schools). The pollsters who were correct in their predictions used yellow pencils, purchased outside of Nicaragua. That pencil sent a message to the interviewees about the “correct answers” that were expected of them.

What the polls say

As important as what the polls say is also what they are silent. Although Russian polls normally take weekly measurements, the WCIOM has not updated them since the week following the invasion, which could suggest that there have been important changes in public opinion as the duration of the war has extended. .

The Russian opposition leader Navalny elaborates on this point in a thread recent on Twitter about a poll on-line.

In a panel survey of Muscovite Internet users, rapid changes in the assessment of Russia’s role in the war are observed. The proportion of respondents who see Russia as the aggressor doubled in the first week of war, from 29% to 53%, while the proportion who considered Russia a “peacemaker” fell by half, from 25 % to 12%.

Although Navalny’s survey method may be questionable, the change in opinion is not so and could point to a generalizable trend. An online panel survey, although inherently biased by excluding non-Internet users, can be very useful in identifying a notable shift or turning point in public opinion that can reverse trends.

Perhaps the most credible public opinion data in Russia is that of the Levada Centera non-governmental research organization that has been conducting surveys since 1988, some in collaboration with the Chicago Council. In 2016 he was labeled a “foreign agent” by the Kremlin.

Levada polls from February 17-21 found that the majority of respondents (52%) viewed Ukraine negatively, while the majority (60%) blamed the US and NATO for the escalation of tensions in eastern Ukraine. Ukraine. Just 4% blamed Russia. In mid-February, even before the start of the “special operation”, there was a noticeable deterioration in people’s attitude towards Western countries. There was an increase in negativity towards the United States, the EU, England and Germany.

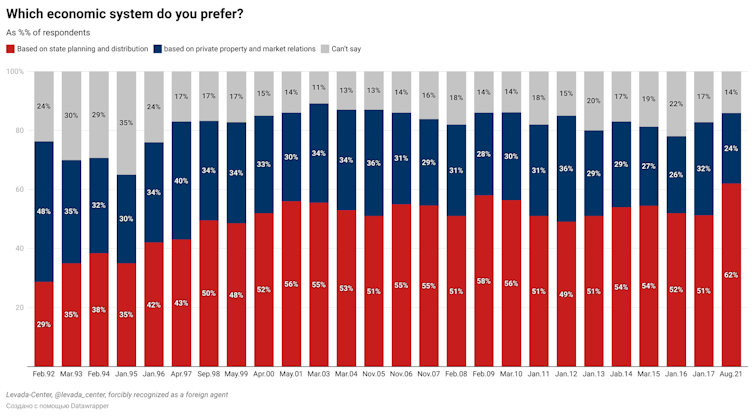

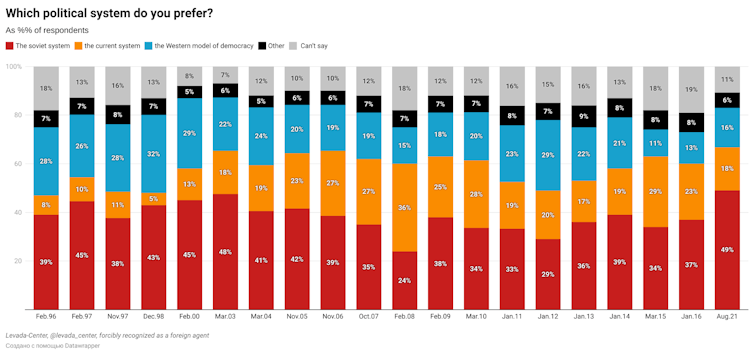

He too Levada Center recently inquired on less circumstantial aspects such as the economy or the role of the State. In October 2021, when asked “which political system is the best?”, 49% answered that the Soviet system, 18% that the current system and 16% that Western democracy. When asked “which economic system is the best?”, 62% of the responses referred to state planning and distribution and 24% to private property and the market. To a large extent, the nostalgia for the Soviet Union in these responses explains much of the support for Putin and the invasion.

Levada Center

Levada Center

All of these perceptions could change as the war drags on, the consequences of which could call Putin’s leadership into question. It is also foreseeable that access to these measurements will become less transparent as the days go by and the conflict worsens.

Russian propaganda aimed at the global south

The numbers indicate that, at least so far, Russian public opinion is on Putin’s side on the invasion. When we say that Ukraine has won the communications battle in this war, we are strictly referring to what is happening in the West. Russian public opinion figures are different, and something similar could be happening in non-Western countries.

A very interesting analysis from carl miller explains how Russian propaganda and its efforts to construct pro-invasion narratives may be being directed at the global south.

Through an analysis of Twitter clusters, Miller very clearly finds that Russian disinformation is aimed more at the BRICS, Africa, Asia and Latin America than to the West. And the message sent is aimed not so much at saving Russia, as at condemning the United States. The narrative that is sought to be placed is that Russia has acted defensively in the face of NATO expansionism and the West’s response would be hypocritical, since it has made other war conflicts invisible.

When we are certain that Ukraine has won the communications battle, we will have to be more cautious in identifying the precise arena in which that war is being waged.

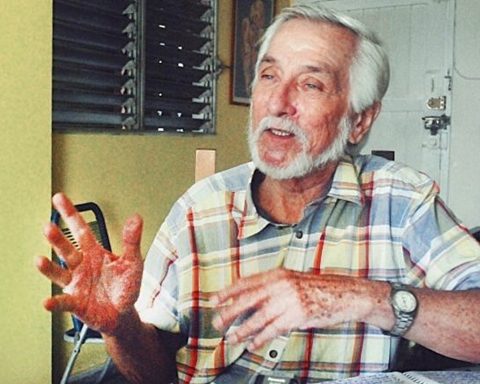

Carmen Beatriz FernandezProfessor of Political Communication at UNAV, IESA and Pforzheim, university of Navarra

This article was originally published on The Conversation. read the original.