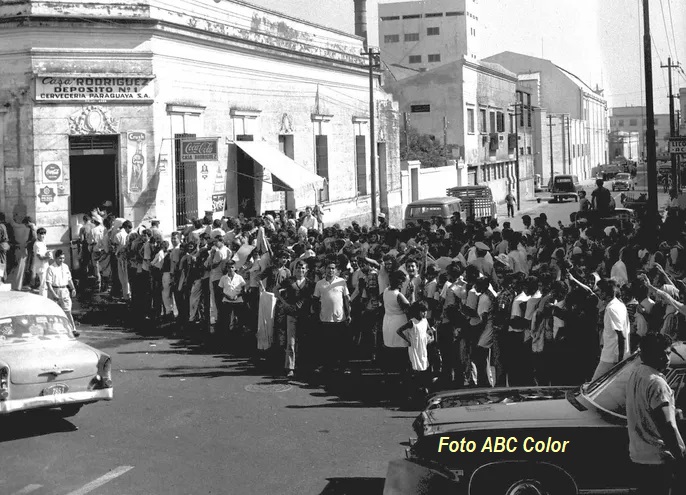

It sounds like gibberish but they are three words and a conjunction that contain a whole history of humanity. Surely it would sound strange to millennials and centennials, in this age of refrigerators, freezers and dispensers, if I told them that you had to go buy ice at the port, in what is still known as the Paraguayan Brewery. There was a queue with a burlap bag and, if there was luck, the bar of ice, weighing a few kilos, would come covered with a layer of sawdust to retard the inevitable melting. The wait was long especially when the end of the year parties approached and you had to find a way to cool the drinks. Then the trip was started on line 4 or 11 with the ice dripping on the floor.

Domestic refrigerators? Of course there were, but only in wealthy homes that sent them to be brought from Argentina or Europe. In the early days they worked with ice bars. Then the “kerosene” refrigerators appeared. They never explained to me how it happened that a little flame at the bottom of the device turned cold.

Only towards the middle of the ’50s would the first “economic” models appear. You had to get a plan in endless installments in the representative, almost like buying a car. One day the Japanese put things in modern terms and invented compact refrigerators, so much so that one brand promoted them with the slogan “small on the outside, big on the inside”. That is, they took up little space in the house. You just had to have an outlet and that’s it. In other words, the 20th century arrived, in refrigerator terms, well into the 1960s. The refrigerator and soon after the television, would become the main furniture in the house and were installed in the living room, so that visitors could admire them.

WATER GOES – Around those same days, in the mid-50s, Corposana appeared, freeing Asunción from the shameful nickname of “the only Latin American capital without running water”. The Sanitary Works Corporation soon dedicated itself to digging trenches to bury pipes, although the phase of covering the holes was not as efficient, the same as now. His bungling reached such a point that very soon street humor changed its acronym and began to call it Corpozanja. The connections were of two types: valve and meter. The first consisted of a half-inch pipe that delivered a rather mean trickle. The installation ended in a simple faucet or in a tank (of the oil barrel type) placed on the roof to function as a reserve. During the Paraguayan summer, with 35 degrees in the shade, it is easy to imagine the temperature that deposit raised. Well seen, it had an advantage, since for much of the year a water heater or an electric shower would not be necessary. If you could stand that boiling water, all good.

That’s why ice was so necessary. The prospect of a glass of cold water made anyone sigh. Among the stalls of Market 4 of those years, children circulated with a bucket and a jug offering “ice water for 1 guaraní”. It was a miracle that we did not die of cholera or dysentery drinking from a jug that had passed through a thousand mouths.

THE ICE MACHINE – The first ice making machine arrived in Paraguay before the war against the Triple Alliance. He had it brought from Europe by an Italian, Domingo Parodi, a Genoese naturalist, pharmacist and medical assistant who settled in the country in 1856. Like many immigrants, Parodi took advantage of his higher education to undertake several activities at the same time, for example, dedicating himself to sailing cabotage in what we know today as the Hidrovía, trading hides and yerba mate. While introducing photography and the lottery to prewar society, Don Parodi decided to open an ice factory importing the necessary equipment from France. After an itinerary very similar to Homer’s Odyssey, the boxes full of pieces that weighed more than three tons arrived in Asunción and were deposited at Parodi’s home while waiting for a technician to assemble the artifact. But the tragedy that would befall the country in 1865 stopped the project. After surviving the contest, the Genoese finally went to Buenos Aires.

The first ice factory finally fell into the hands of post-war politicians who, after some lobbying, handed it over as a monopoly to a foreigner named Junquer. If manufacturing only ice was a business in the dilapidated Asunción at that time, the Frenchman should have become a millionaire.

ICE CREAM IN ROME – “The gargantuan banquets in Nero’s Domus Aurea lasted for hours, sometimes days, and ended with a round of exquisite ice creams…”

How did they make ice cream in Rome? Simply, bringing ice from the snowy peaks of Mounts Livato, Terminillo and other peaks relatively close to the city. There they cut it into large blocks that they wrapped in burlap and skins to transport them without wasting time to Rome. Thousands of slaves were in charge of keeping active that true cold chain that guaranteed the enjoyment of the emperor’s guests.

Snow-covered glasses to cool shellfish, cherry, honey and lemon sorbets… It happened thousands of years ago, although only in the mansions of the rich. Today, from the ice cream stick of recent history to the most refined confectionery products below zero, ice and ice cream are a part of daily life without us wondering how they are made.