September 19, 2022, 0:59 AM

September 19, 2022, 0:59 AM

Russia’s withdrawal from Kharkiv in northeastern Ukraine has exposed key weaknesses in supplies and personnel in the country’s armed forces, Russian veterans and military bloggers say.

“You have no idea how tired I am of greeting someone in the morning and then having to identify their remains later that day.”

That phrase was allegedly entrusted – by phone – by a Russian officer, who works as a marine in Ukraine, to a former colleague who published it on his Telegram channel.

“Just yesterday, two of my sniper groups were destroyed by a tank. Three men were killed instantly, the fourth fought for his life for an hour and a half, another, in critical condition, was taken to hospital. We barely have any men left and we are keeping a front line tens of kilometers long“.

As Russian officials and state media try to downplay the withdrawal of Russian forces from Kharkiv, war reporters, veterans and influential military bloggers acknowledge numerous challenges in closed messaging channels.

Blogs and Telegram channels are full of stories about inadequate staff and equipment, a situation made worse by a rigid operating hierarchy.

leadership concern

A Telegram channel that shared experiences of soldiers in Ukraine shortly after the latest withdrawal describes how even the deployment of a small surveillance drone must be approved by a senior officer or general, which slows down the understanding of enemy positions considerably.

Another channel on Telegram, allegedly run by a veteran of the Russian special forces, posted a photo of a Russian soldier with an embroidered arm patch with the words: “There is no worse opponent than your own commander who is a…” , adding an insult to describe it.

There is no way of knowing where and when that photo was taken, but what is significant is that it has been widely shared by both veterans and forces on the battlefield, suggesting that it reflects popular opinion among the troops.

Despite the rumors of low moralsRussian war reporters and paramilitary soldiers in Ukraine do not suggest that widespread desertion in the field contributed to the latest defeat in eastern Ukraine.

They say it is much more likely that the units simply obeyed an order to withdraw.

Some Russian fighters on another channel bitterly joke that the “special military operation,” as the Russian government publicly calls it, “has no goals, it only has one path.”

There are not only concerns about poor leadership.

Basic equipment seems to be so scarce that fundraising has had to be done. Dozens of public social media groups are raising money for a wide range of kits, from drones to tights and underwear.

One of them, called “Popular Front,” says it has raised about 1.5 billion rubles (about $17 million) in the past three months and has already spent it on uniforms, helmets and bulletproof vests, as well as first-aid kits. aids, binoculars and thermographic cameras.

Despite such fundraising, hundreds of requests have been posted online by dozens of military units, including pilots of Russia’s most modern fighter jets, for specific items such as fire-retardant uniforms, torches and two-way radios.

But the problem It’s not just the lack of suppliesis the lack of soldiers.

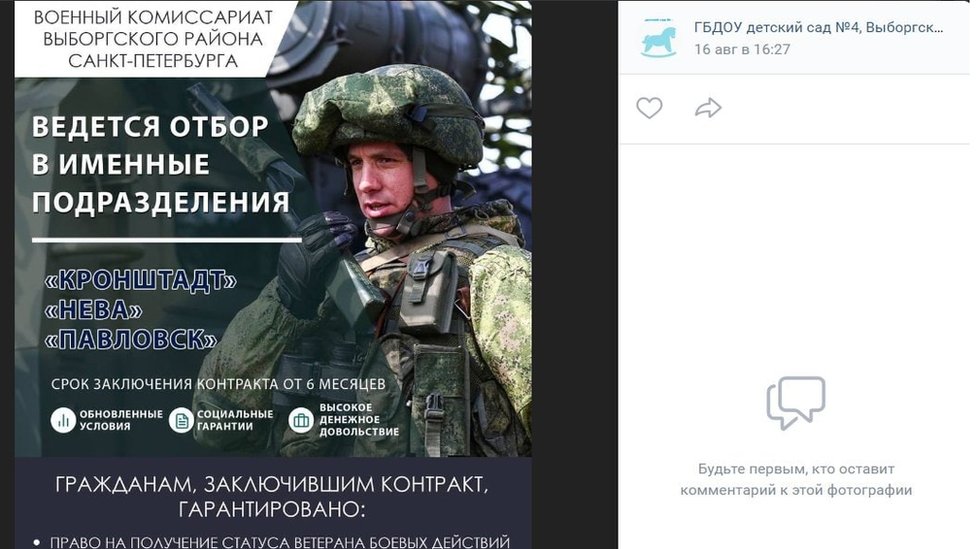

Recruitment

While there are no signs of an imminent conscription, there has been one that is described by the government as an “informal mobilization” that began shortly after the invasion of Ukraine.

The Russian Defense Ministry began posting ads on popular employment websites in early March, something that, before the war, it was rarely done.

One website lists more than 7,000 military vacancies for gunners, mortar crews, and other combat-focused roles.

None of the ads mention the “special military operation” in Ukraine.

Also flyers have been distributed with door-door recruiting information and have been displayed on public transport and outside residential apartment blocks and even in psychiatric hospitals.

Recruitment centers have also resorted to calling soldiers who have left or retired to ask them to rejoin, some of those contacted told the BBC.

A soldier who fought in Chechnya in the 1990s says he and his friends were called up three or four times.

The man, who asked to remain anonymous, says he eventually agreed but later refused to sign the contract, put off by what appeared to be bad conditions.

Possibly to make serving a more attractive proposition, the minimum contract length was lowered from three years to three months, and the upper age limit for a first contract was raised from 40 to 60 years.

Advertised monthly salaries range from 100,000 to 450,000 rubles ($1,139-$5,125), a tempting proposition despite the dangers of deployment for those with poor job prospects in economically disadvantaged areas of the country.

Russia is believed to send several of these units to Ukraine every 10 days, after training for only a week or even less.

Pressure

Two separate sources on the front lines told the BBC that such units, made up of short-term contract soldiers and fighters from the Wagner mercenary group, whose leader was filmed recruiting at a central prison, make up the bulk of the force. first line that Russia currently possesses.

There are reports that not everyone who signs contracts may do so voluntarily.

Russian human rights activists say there have been cases of men in Chechnya being pressured by the authorities to join.

Russian independent journalists have reported that up to 500 convicts have also enlisted.

One prisoner, Konstantin Tulinov, was praised in state media after he was killed in combat in July.

Tulinov had served multiple sentences, most recently for torturing inmates in Russian prisons.

While these challenges are being discussed in closed groups, there has been no official acknowledgment of the withdrawal.

On his private Telegram channel, influential state war reporter Yevgeny Poddubny suggested that the latest defeat exposed long-standing problems.

“The situation is really tough for our soldiers. The problems that have been discussed both in the public space and in confidential meetings have become evident,” he said.

But there is no evidence that this message is reaching the top.

Poddubny and several war reporters were seen briefly speaking with President Vladimir Putin on the sidelines of the St. Petersburg economic forum in June.

While it’s unclear exactly what they managed to explain to the president, lack of supplies remains a key problem for the Russian military.

Now you can receive notifications from BBC World. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.