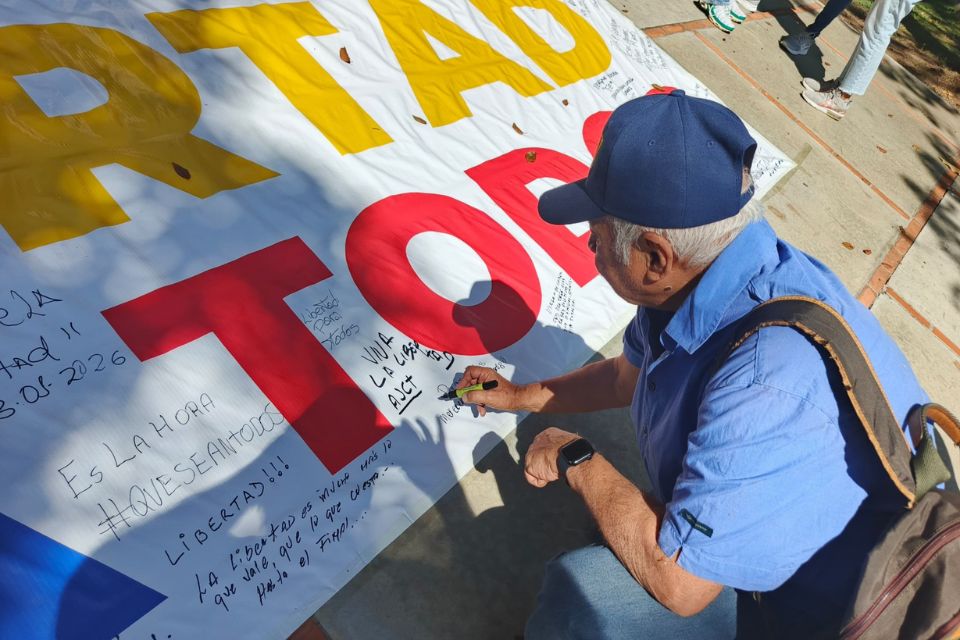

Rafael Uzcátegui and Juan Carlos Apitz question that the proposed “Amnesty Law for National Coexistence” is limited and leaves too much room for interpretations by the same bodies that have sustained the persecution. Both warned that, as it is written, it can exclude many cases, block the truth and open a door to impunity.

The first critical reactions to the proposal for the “Amnesty Law for National Coexistence” marked the edition of Night D transmitted by SuchWhich after knowing the text of 13 articles disclosed by deputy Luis Florido. The sociologist and human rights defender Rafael Uzcátegui (Laboratorio de Paz) and the lawyer Juan Carlos Apitz (dean of the Faculty of Legal and Political Sciences of the UCV) agreed that the instrument, as proposed, does not guarantee that it covers all political prisoners nor that it establishes real bases of non-repetition.

Uzcátegui opened his analysis with a warning: the legitimate urgency for the freedom of detainees cannot become social pressure to approve “any law” without discussion. In the program he recalled recent statements by the president of the National Assembly, Jorge Rodríguez, who linked new imprisonments with the approval of the text and promised immediate results. For Uzcátegui, this message is “dangerous” because it plays with the pain of family members and raises expectations that the wording of the project itself does not support.

One of the central points was the scope. Although Article 6 sets a general period between January 1, 1999 and January 30, 2026, the proposal lists 10 specific episodes and describes them, for the most part, as “politically motivated acts of violence.” Uzcátegui insisted that this formulation leaves out people detained for expressing themselves, for political organization or for causes that do not fit into a narrative of violence. He also warned about cases that occur outside the detailed time windows: if the list remains a rigid filter, many files may not qualify.

Along the same lines, Uzcátegui questioned that the concept of “political or related crimes” was introduced from the first article without a precision that avoids ambiguity. He warned that this vagueness could facilitate readings that dilute responsibilities for human rights violations or present them as “related” to a conflict, without the need for an explicit amnesty for those responsible.

Article 7, which lists exclusions (serious violations of human rights, crimes against humanity, war crimes, intentional homicide, drugs, crimes against public property), was described by Uzcátegui as “particularly problematic” in the Venezuelan context. His argument was not that these exclusions are meaningless in the abstract, but that in practice many political prisoners have been charged with criminal offenses used instrumentally. In his opinion, if the system has “invented” charges to justify arrests, then excluding crimes such as public property or drugs can translate into leaving people prosecuted under questionable files without protection.

Another focus of alarm was article 8, which proposes the extinction of criminal, administrative, disciplinary and civil actions linked to the amnestied events. Uzcátegui maintained that, with that wording, the law could operate as a “silent impunity”: it does not openly amnesty human rights violators, but it closes paths to investigate, punish or claim future responsibilities for the included episodes.

Article 9 reinforced their doubts about the actual application: it establishes that a court, at the request of the Public Ministry, will verify the amnesty assumptions case by case and will decree dismissals or reviews. Uzcátegui stressed that the rule does not imply automatic releases and places the decision in the hands of “the same courts” and the same Public Ministry that have processed the processes that are questioned today. In addition, he noted the absence of clear deadlines, which leaves open the possibility of delays.

Regarding article 11, which orders the elimination of records or antecedents of beneficiaries, Uzcátegui said that it may sound positive in a simple reading, but it puts the right to the truth and institutional memory at risk. He stated that, if we try to delete files, it will be difficult to reconstruct how arrests, accusations and responsibilities occurred. In his opinion, if we want to prevent the antecedents from continuing to weigh on the victims, the text should provide for institutional protection mechanisms (not elimination) so as not to block future investigations.

Apitz, for his part, added criticism from the legal side and from his recent experience in the National Assembly, where he said he had denounced the legislative opacity around the project. He stated that they were called to give their opinion without the text being available in a clear and timely manner, and that this lack of transparency fueled confusion, even about what exactly was approved in the first discussion.

Regarding the content, Apitz warned that the promise of immediate releases after approval does not correspond to the planned procedure itself: as he explained, the application requires applications before the competent courts. He also stated that the project, as he read it, does not contemplate military personnel prosecuted for crimes linked to political issues, which would leave that group out of the benefits.

The dean also listed a gap that he considers structural: the proposal does not include repealing norms that have served to persecute dissent. He expressly mentioned the need to repeal the 2017 anti-hate law; the Liberator Simón Bolívar Organic Law of 2024; the law that regulates and supervises NGOs of 2024; the Organic Law of Asset Forfeiture of 2023 (in particular articles that allow seizures without full guarantees, as noted); organized crime law provisions used to deny procedural benefits; and article 105 of the Organic Law of the Comptroller’s Office, associated with disqualifications without a final criminal sentence. In his opinion, without this component, the amnesty can become an isolated gesture that does not prevent new arrests.

Apitz also raised two absences that, from his perspective, affect the sense of reconciliation: an explicit request for forgiveness from the State to political prisoners and mechanisms to repair damage to the victims and their families. He argued that thinking differently “is not a crime” and that a law aimed at coexistence should reflect that recognition, not language that suggests guilt.

Both guests agreed that, although there is a social expectation to release detainees, hasty approval with ambiguities and without guarantees of non-repetition can deepen tensions: due to exclusions, due to the margin of discretion and due to the risk of dividing family members and victims between “included” and “excluded.” They also warned that the debate should not be reduced to urgency, but to quality and the effects that the text leaves for the future.

*Read also: The limitations of an amnesty law: who can be excluded?

*Journalism in Venezuela is carried out in a hostile environment for the press with dozens of legal instruments in place to punish the word, especially the laws “against hate”, “against fascism” and “against the blockade.” This content was written taking into consideration the threats and limits that, consequently, have been imposed on the dissemination of information from within the country.

Post Views: 57