AND

Between the 1960s and 1970s, On the Latin American left as a whole, Mao Tse-Tung’s analysis of pre-revolutionary China had a marked impact on social inequality and US meddling in the continent. The concentration in Mexico of marginal popular groups thus presented a large base of support for an ideology that preached the message of the Great Helmsman of radical egalitarianism and rigorous social justice.

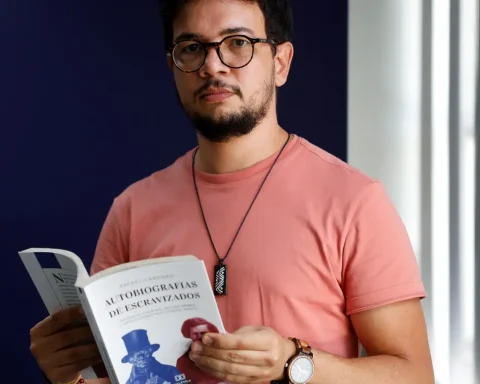

Benjamin Gonzalez Suarezhttps://cutt.ly/oNQW0Ww) was far from the only Mexican who dreamed of a Maoist people’s war in those years. Teresa Molina Avella also thought about the Chinese strategy of surrounding the cities from the countryside. This article examines what influenced the politicization of these two young people and what led them to join Acción Popular-Marxista Leninista (AP-ML).

Benjamin said that his family heritage was one of the causes of his politicization and inclination to the left. He remembered it this way: I did not approach politics, my father approached me

. Antonio González Mondragón, his father, was first a member of the Mexican Communist Party (PCM), then joined the Maoist-leaning Revolutionary Party of the Mexican Proletariat (PRPM). In this way, the González family adopted Maoism as a political and ideological reference. Similarly, Teresa approached politics within the immediate circle of her family. She remembers that my mom and dad were very active in social justice issues through grassroots church communities

.

Similarly, the cultural production of the time influenced the political formation of Benjamín, who began to listen to songs by Judith Reyes and José de Molina, which spread the social and political struggles of those years. Another influence that sensitized Teresa was her relationship with the popular theater group Mascarones, whose purpose was to make social criticism and bring theater closer to the communities through performances from town to town.

In the field of higher education, Benjamín met two student activists, with whom he shared interests and concerns. Over time they recruited him: It was more because of Jorge Melo and Armando Mier that I joined Acción Popular

. In this context, Teresa began a relationship with a student from the Faculty of Economics of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). It was through her partner that she joined Acción Popular: “And then she invited me to the organization, and a few days later this boy gave me the selected works of Lenin; that was first, then he gave me the selected works of Mao and The five philosophical theses.

In this way, Benjamin and his Popular Action comrades applied a Maoist ethic that manifested itself in the principle of serving the people. While Teresa’s cell focused on analyzing the contradictions, she remembers it this way: “ The five philosophical theses ficas of Mao were like candles everywhere, we argued about who is against and who is in favor, who has more strength. We were thinking about how to resolve a certain contradiction and what our role should be in that process.” They became assiduous readers of the magazine Beijing Reportssince they wanted learn from the Chinese, how the people were motivated, how the demands of the people were raised

.

The Popular Action militants were aware of Mao’s insistence on the primacy of practice, so they learned to work, with their ideals and convictions ahead. Benjamin organized the peasants of Xoxocotla, Morelos, and led a taking of land in Pino Resineros, in San Pedro Piedras Gordas, municipality of Villa Madero, Michoacán. And he recruited students from the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo (UMSNH). On her side, Teresa distributed the newspaper People’s Workers Struggle in the factories of IACSA, Nissan and in the premises of the independent unions in the state of Morelos. She also carried out awareness work among the students of the Autonomous University of Guerrero.

Comparing from memory the processes of politicization and integration into militancy of these two young people allows us to understand the different assessments they make of the stages of their lives and the ways in which they interpret the revolutionary upsurge of their time. At the same time, it helps to understand how they reconfigured Maoism in their political activities.

*Historian of the UMSNH and author of the book The power comes from the rifle