Will the United Nations expert take into account that the rights crisis in Cuba has internal components that transcend the sanctions regime?

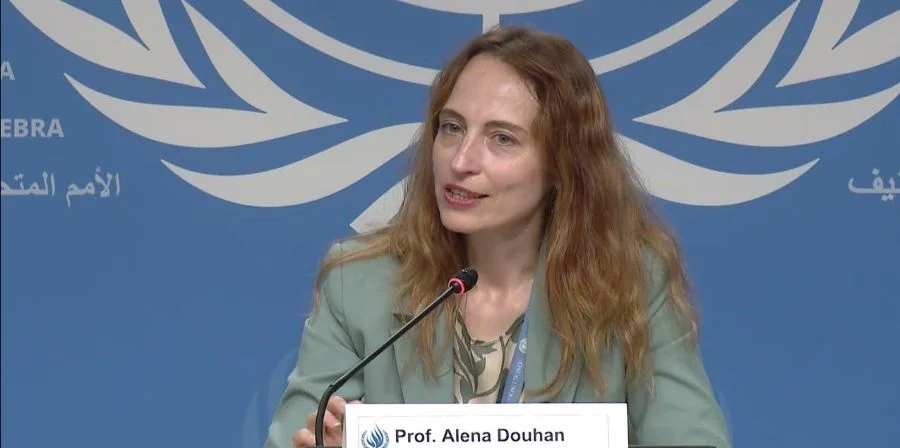

MIAMI, United States. – The UN special rapporteur on unilateral coercive measures, Alena Douhan, will make an official visit to Cuba from November 11 to 21 to evaluate the impact of sanctions on human rights. The Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) advertisement that the expert “will present her conclusions and recommendations in a report that she will submit to the 63rd session of the Human Rights Council in September 2026.”

The rapporteur will examine “to what extent the adoption, maintenance or application of unilateral sanctions, the means of their execution and over-compliance impede the full realization of the rights” enshrined in the Universal Declaration and other instruments, “in a spirit of cooperation and dialogue,” according to the official call.

The visit comes protected by the mandate created by the Resolution 27/21 of the Human Rights Council (2014), which emphasizes that unilateral coercive measures and their legislation “are contrary to international law” and that, in the long term, “they can cause social problems and raise humanitarian concerns” in the States targeted by them. The mandate page itself recalls that the rapporteur was established to “gather all relevant information” on these impacts, study trends and formulate recommendations.

The OHCHR questionnaire asked for concrete examples of rights affected in Cuba—including health, education, social protection, and the right to development—as well as information on the hardest hit sectors (energy and critical infrastructure, among others), the effect of humanitarian licenses and exemptions, and how “zero risk policies” and “overcompliance” by banks and companies block even permitted operations.

She also asked if the repeated classification of Cuba as a “State sponsor of terrorism” affects human rights and invited proposals for actors with whom the rapporteur should meet in Havana.

In parallel, the United Nations reported that Douhan – a Belarusian academic who has held the mandate since 2020 – will arrive in Cuba to evaluate the effects of primary, secondary and over-compliance sanctions.

The sanctions review will take place in an environment where access to independent civil society is restricted. Cuba does not maintain a “standing invitation” to the Council’s special procedures —a common cooperation practice in other States—, and its relationship with thematic visits has historically been limited, according to the official records of the UN itself.

In addition, a documented pattern of harassment, arbitrary arrests and house arrests persists to prevent the participation of activists, journalists and relatives of prisoners in public meetings or events. Human Rights Watch describe serious abuses against protesters detained after the July 2021 protests and points out that, despite some conditional releases at the beginning of 2025, “hundreds” remain imprisoned.

Amnesty International, for its part, warns that, after the entry into force of the new Penal Code In 2022, criminalization, arbitrary arrests and harassment intensified, particularly against journalists and critics, in a climate of “completely restricted civic space.”

Recent reports from the IACHR detail surveillance operations, illegal subpoenas and selective Internet shutdowns to immobilize dissidents, practices that could limit who manages to meet privately with the rapporteur.

The use of standards such as Decree-Law 370 (on computerization) and the Decree-Law 35 (about telecommunications) —pointed out by international organizations and media as tools to restrict freedom of expression online—also sets up a scenario in which non-state organizations, often without legal status, operate under the risk of sanctions and communication blockade.

Douhan’s mandate has put the focusin addition to direct sanctions, in “overcompliance”: the tendency of banks and companies to block legal operations for fear of sanctions or fines, a phenomenon that the rapporteur recently described as a trigger for “reputational risks” that paralyzes permitted transactions. In his report to the Council in July 2025, he warned that overcompliance by financial entities has even hindered payments for essential goods.

The OHCHR questionnaire asks about the impact of sanctions on health, education, energy, social protection and employment; due to the effect on older people, people with disabilities and populations in vulnerable situations; for migration and migrant rights; and by how humanitarian exemptions operate in practice to cover basic needs. It also requests examples of “zero risk policies” from banks and companies that block permitted interactions with Cuban institutions and sectors.

This approach coexists with another verifiable reality: the rights crisis in Cuba has internal components that transcend the sanctions regime. HRW and Amnesty have consistently documented the persecution of dissent, severe restrictions on freedom of expression and association, and the existence of a high number of political prisoners.

Emblematic cases, such as the new arrest of the opponent José Daniel Ferrer in April 2025, reaffirm the continuity of punitive practices and the use of precautionary measures to control critical voices, even after conditional releases.

Douhan will meet in Havana with authorities, UN agencies, international and regional organizations, diplomatic corps and “non-governmental organizations, business community, civil society and academics,” according to the official call.

The effectiveness of the visit will depend largely on the possibility that the rapporteur has access without interference to non-state actors and victims—including families of prisoners—in a country where the UN has observed the absence of a permanent invitation to special procedures and the IACHR and independent organizations report systematic obstacles to civic participation.