The UN Mission for Venezuela also maintains that the political persecution included children and adolescents.

MIAMI, United States. – State repression in Venezuela intensified after the presidential elections of July 28, 2024, with a pattern of arbitrary detentions—massive and selective—, torture, mistreatment and sexual violence in detention centers, in addition to criminal proceedings without guarantees and the use of figures such as “terrorism” and “incitement to hate” to punish dissent, according to the most recent findings of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR/OHCHR), presented to the Human Rights Council in Geneva.

In its update on the period after 28J, the UN Mission maintained that the political persecution also included children and adolescents: the mechanism documented that at least 220 minors (from 13 to 17 years old) were detained in that context and that, during their detention, episodes of incommunication, cruel treatment, acts of sexual violence and violations of due process were recorded, without consideration for their age or their best interests.

The Mission’s diagnosis does not describe isolated events, but rather a logic of repression. In its most recent report, released on December 11, the team pointed out the Bolivarian National Guard (GNB) as a key actor in the execution of systematic violations. The report includes massive and selective arbitrary detentions, physical violence during arrests, planting of evidence, as well as torture, mistreatment and sexual and gender violence within GNB facilities used as temporary detention centers.

The head of the Mission, Marta Valiñas, stated: “The torture, ill-treatment and acts of sexual violence that we have verified – including assault and rape – were not isolated incidents. They are part of a pattern of abuse used to punish and break victims.”

The United Nations reading connects that pattern with the post-electoral moment. Last September, when presenting another report to the Council, the Mission warned that the repression after the elections was expressed through the detention of opponents and people perceived as such, and reported that in that cycle serious acts were committed that included sexual torture and other ill-treatment, in addition to deprivations of liberty without guarantees.

The Office of the High Commissioner, for its part, has described the same period as a sustained deterioration of civic space. In a statement on August 2, 2024—just days after the elections—the OHCHR warned about ongoing arbitrary arrests and the disproportionate use of force, and questioned whether many people were being accused or charged for “hate incitement” or through anti-terrorism legislation, warning that criminal law should not be used to unduly restrict fundamental freedoms.

This same month, Volker Türk took that concern one step further stating before the Council that the situation “has not improved” and that he found the testimonies about authorities encouraging complaints among citizens through a state-sponsored mobile application “shocking,” a practice that, he said, “fuels fear, distrust and self-censorship.” In the same intervention he mentioned the impact on civil society and journalists, in a climate of restrictions and arbitrary arrests.

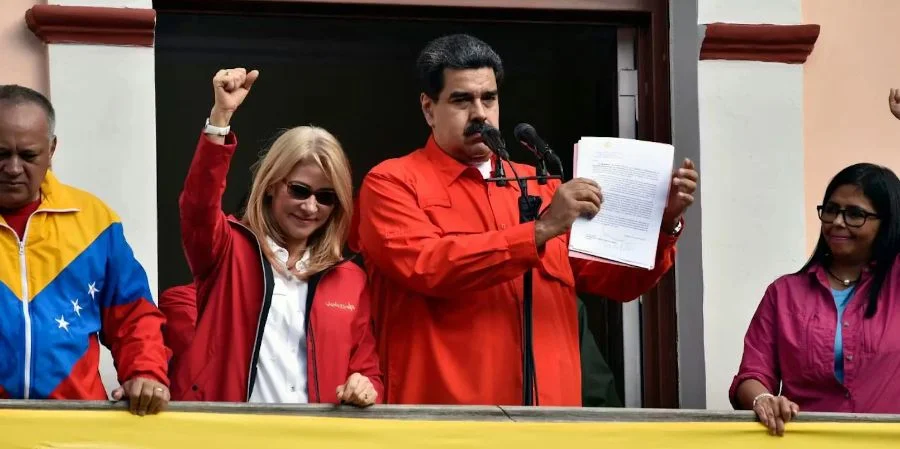

The presidential elections of July 28, 2024 were the immediate breaking point of the cycle of repression that UN mechanisms document today. The National Electoral Council (CNE) proclaimed Nicolás Maduro the winner with a result close to 52%, but the announcement was mired in controversy due to the lack of a public and verifiable breakdown by voting centers at the most critical moment.

The opposition, led politically by Maria Corina Machado and with Edmundo González as a candidate, he made public minutes and records that demonstrate the opposite.

Even the Carter Center of the United States Indian that the process “did not meet” international electoral integrity standards and said that it could not verify or corroborate the results declared by the CNE, especially questioning the absence of data disaggregated by table or center.

In parallel, the OHCHR warned weeks after the post-election crisis was fueled by arbitrary arrests and the use of criminal offenses such as “incitement to hate” or anti-terrorist legislation against detained people, in a context where the UN insists that criminal law should not be used to unduly curtail basic freedoms such as expression, association and peaceful protest.