Although discrete in numbers, the presence japanese In Cuba it has been intense in cultural, economic and emotional imprints. Between the memory of the first immigrants and the practices of their descendants, a history of integration is woven that spans more than 100 years.

The oldest documented link between Japan and Cuba dates back to 1614, with the stopover in Havana of the samurai and diplomat Hasekura Tsunenaga. This would be the symbolic antecedent of the Japanese who began to arrive on the island at the end of the 19th century, particularly young men with plans to work and eventually return to their land of origin.

Japanese immigration to Cuba took place in several periods between 1898 and the post-war period, with settlements scattered throughout almost the entire country and a relevant nucleus in the then Isle of Pines. Despite the initial expectations of those who arrived, the political and economic crises, added to changes in immigration laws, pushed many to put down permanent roots on the island.

During World War II, Japanese immigrants were viewed as “enemy aliens” and many suffered imprisonment, confiscation, and surveillance by authorities. But although this dark experience left deep marks on the Japanese community, the majority decided to stay and rebuild their lives and businesses, assuming Cuba as a second homeland.

The Cuban community of Japanese descendants, known as Nikkei, today numbers around 900 people, with a notable presence in Havana and the Isle of Youth. Its members combine Japanese surnames, family customs and a mostly Cuban identity, with values associated with discipline, punctuality and responsibility attributed to their Japanese heritage.

In daily life, descendants have preserved cultural fragments: culinary references adapted to local ingredients, family narratives about war and exile, and a work ethic visible in spheres such as agriculture, sports and martial arts, where Japanese pioneers were key in the introduction of jiu jitsu and karate-do to the island.

With a sense of community and territorial structures that function as spaces of support, transmission of memory and articulation with Japanese institutions, the Cuban Nikkei keep alive the heritage of their ancestors and are, at the same time, an effective bridge between Japan and Cuba, in a framework of bilateral relations that includes cooperation, scholarships and humanitarian aid.

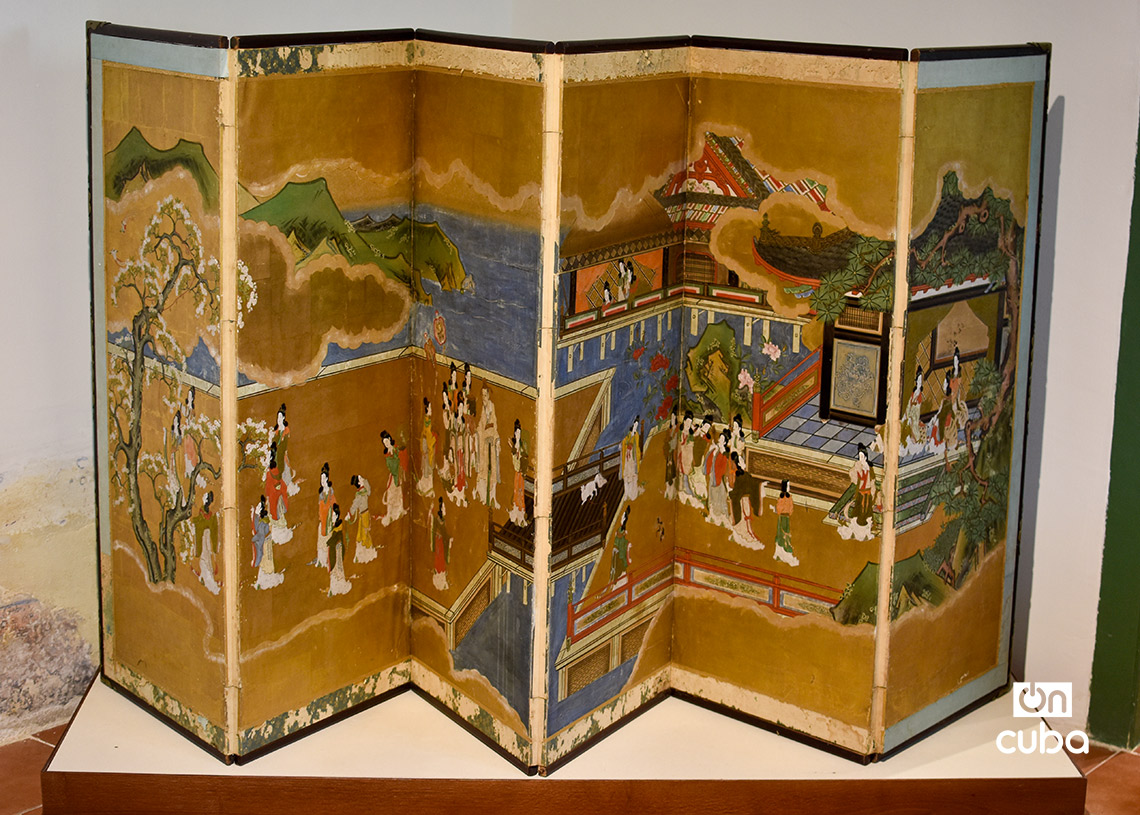

Places such as the Columbus Cemetery —where Buddhist ceremonies are held in front of the pantheon of the Japanese colony—, the Casa de Asia with its collections from the Asian country, and the monument to the first samurai who set foot on Cuban soilare some of the places where Japan’s footprint in Cuba is preserved today. Photojournalist Otmaro Rodríguez brings us closer to them today with his images.