An investigation speaks of the discovery of archaeological remains of the pre-Hispanic Casarabe culture in the Bolivian Amazon until now unknown. A team led by Heiko Prümers of the German Archaeological Institute used LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) technology, which uses an airborne laser scanner to obtain a 3D map of the terrain.

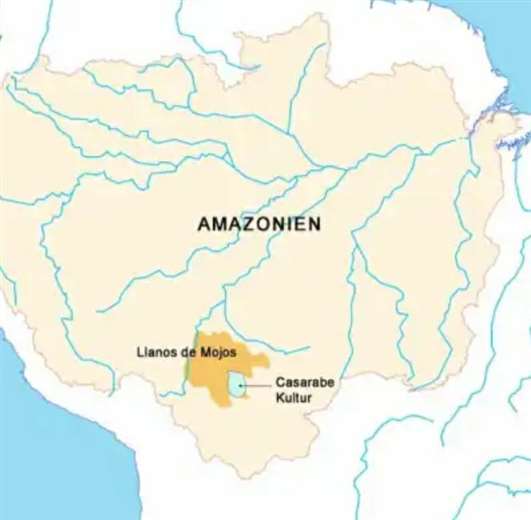

The study was published in the journal Nature, where two large settlements already known but not explored, Cotoca and Landívar, and 24 other smaller sites are documentedonly 15 were known to exist, all of them in Llanos de los Mojos (southeast Bolivia).

The use of LIDAR, which makes it possible to “make the vegetation disappear”, led to the identification of artificial terraces or hills five meters high and up to 22 hectares (30 soccer fields), on which there were U-shaped civic-ceremonial structures and conical pyramids up to 21 meters high, as in Cotoca.

The Casarabe culture, also known as the region of the monumental mounds, It developed between the years 500 and 1400 of our era, in the southwest of Llanos de los Mojos, an area of patches of savannah and tropical forest.

Until now, what is known about Casarabe comes from twenty years of excavations in Loma Salvatierra and Loma Mendoza (both in the Llanos de Mojos), where among other materials, remains of 120 burials have been found.

For the current study, in 2019 the team together with Prof. Dr. José Iriarte and Mark Robinson from the University of Exeter, mapped a total of 200 square kilometers of the Casarabe cultural area. The evaluation carried out by the company ArcTron3 gave rise to a surprise. What came to light were two remarkably large sites, 147 and 315 hectares, in a dense four-tier settlement system. With a north-south extension of 1.5 kilometers and an east-west extension of approximately one kilometer, the largest site found so far is as large as Bonn was in the 17th century, says co-author Dr. Carla Jaimes Betancourt.

This culture developed in a landscape with a “huge seasonal contrast”, with more than four months of drought, which during the dry period cracked the clay with which they made their constructions, but in the rainy season the savannah was covered with a layer of water.

Iriarte stressed that they invested “a lot in managing that environment with the construction of embankments and canals” to take advantage of the water and plant in a soil that was “particularly rich” due to the large amount of sediments deposited during the middle Holocene.

“Of what has been mapped, and it is only a small part of what can be seen, there are a thousand kilometers of canals and embankments,” said Iriarte, who in his 20 years of work in the Amazon has contributed to archaeobotanical studies, which indicate that the forest did not decline, although it could be thought that a culture of this type would make large fellings.

The Casarabe culture “fits into early low-density tropical urbanism,” which also existed in places in Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, or Central America, which leaves aside the idea that the western Amazon was sparsely populated in pre-Hispanic times, the study indicates.

An investigation speaks of the discovery of archaeological remains of the pre-Hispanic Casarabe culture in the Bolivian Amazon until now unknown. A team led by Heiko Prümers of the German Archaeological Institute used LIDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) technology, which uses an airborne laser scanner to obtain a 3D map of the terrain.

The study was published in the journal Nature, where two large settlements already known but not explored, Cotoca and Landívar, and 24 other smaller sites are documentedonly 15 were known to exist, all of them in Llanos de los Mojos (southeast Bolivia).

The use of LIDAR, which makes it possible to “make the vegetation disappear”, led to the identification of artificial terraces or hills five meters high and up to 22 hectares (30 soccer fields), on which there were U-shaped civic-ceremonial structures and conical pyramids up to 21 meters high, as in Cotoca.

The Casarabe culture, also known as the region of the monumental mounds, It developed between the years 500 and 1400 of our era, in the southwest of Llanos de los Mojos, an area of patches of savannah and tropical forest.

Until now, what is known about Casarabe comes from twenty years of excavations in Loma Salvatierra and Loma Mendoza (both in the Llanos de Mojos), where among other materials, remains of 120 burials have been found.

For the current study, in 2019 the team together with Prof. Dr. José Iriarte and Mark Robinson from the University of Exeter, mapped a total of 200 square kilometers of the Casarabe cultural area. The evaluation carried out by the company ArcTron3 gave rise to a surprise. What came to light were two remarkably large sites, 147 and 315 hectares, in a dense four-tier settlement system. With a north-south extension of 1.5 kilometers and an east-west extension of approximately one kilometer, the largest site found so far is as large as Bonn was in the 17th century, says co-author Dr. Carla Jaimes Betancourt.

This culture developed in a landscape with a “huge seasonal contrast”, with more than four months of drought, which during the dry period cracked the clay with which they made their constructions, but in the rainy season the savannah was covered with a layer of water.

Iriarte stressed that they invested “a lot in managing that environment with the construction of embankments and canals” to take advantage of the water and plant in a soil that was “particularly rich” due to the large amount of sediments deposited during the middle Holocene.

“Of what has been mapped, and it is only a small part of what can be seen, there are a thousand kilometers of canals and embankments,” said Iriarte, who in his 20 years of work in the Amazon has contributed to archaeobotanical studies, which indicate that the forest did not decline, although it could be thought that a culture of this type would make large fellings.

The Casarabe culture “fits into early low-density tropical urbanism,” which also existed in places in Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka, or Central America, which leaves aside the idea that the western Amazon was sparsely populated in pre-Hispanic times, the study indicates.

;