The United States Trade Representative (USTR) excluded Nicaragua from the reallocation of the additional sugar quota for fiscal year 2022, sending the first ‘message’ to the Government regarding the application of measures contemplated in the Renacer Lawwhich include the review of CAFTA.

In the 1980s, the United States signed a commitment within the framework of the World Trade Organization (WTO), to acquire an annual amount of tons of sugar, which is distributed among the producing nations. During the government of President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, Nicaragua was assigned only 1.98% of that quota, in part because, having no previous trade with the US, there was no history that would allow calculating the percentage to be assigned. .

That 1.98% currently represents some 22,083 tons, but that quota, as well as the 29,000 tons negotiated within the framework of the Free Trade Agreement between the Dominican Republic, Central America and the United States “is safe,” he told CONFIDENTIAL an industry source who preferred anonymity.

When the sugar nations cannot cover the allocated quotathe USTR reallocates it to the rest of the countries according to its own criteria, which is usually translated as a political message, to the extent that more, or less, is assigned to a country.

As an example, the source recalled that “two years ago, 100% of the quota (about 250,000 tons at the time), was assigned to Brazil, because the United States wanted to support President Bolsonaro, who was in trouble.” .

This year, partners such as the Dominican Republic, Brazil and Australia received 40,000, 37,182 and 21,284 tons respectively, out of a total quota calculated at 201,551 tons.

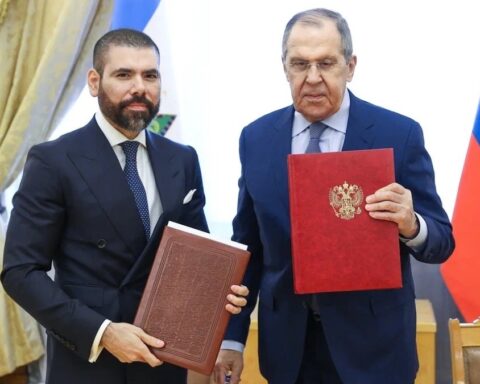

Guatemala was the most benefited from this reallocation, receiving an additional 12,309 tons, while El Salvador (whose president, Nayib Bukele, regularly contends with the US), received 6,667 tons. Panama (7,437), Costa Rica (3,846), Belize (2,821), and Honduras (2,564), close the reassignment to Central America.

During the three reallocations carried out in 2021, Nicaragua obtained additional quotas for around 5,000 tons that not only enter the United States with low tariffs, but also at a preferential price, which can be 80% to 100% higher than what is acquired outside of the fee.

Although it falls within what is called ‘technical action’, the measure is part of the US administration’s policy, to put pressure on the regime of Daniel Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murilloto make them accountable for the deterioration of democracy and human rights in Nicaragua.

Affects producers

The problem is that “this hurts private producers, not the government,” said an industry source, consulted earlier.

“Basically, the message is that the United States is going to close all negotiations with Nicaragua, and that there will be no safeguard that can protect the commercial relationship with the United States, which is only going to deteriorate,” he said in a previous interview, the former liberal deputy, Eliseo Núñez.

“If this is a message, it would not be for the government, which makes very little money from sugar exports, because they are exports within the framework of Cafta, but for the owners of the sugar mills,” said a source who knows how Washington’s decision-making machinery works.

“But if it is a message, it would be a light message, because sugar represented only 2% of the commodities exported to the US in 2021. It would be something like ‘don’t play the government’, but there are better methods, because this won’t tickle the Nicaraguan private sector, he explained.

Indeed, total sugar exports represented income of almost 300 million dollars, between 2020 and 2021, in addition to generating around 35,000 direct jobs and 4% of GDP. 800 private producers sell their harvest to sugar mills established in the country.

Although it is considered that the president of the United States, Joe Biden, cannot exclude Nicaragua from Cafta without canceling the entire treaty, the signing of the Renacer Law allows him to evaluate all the diplomatic and economic tools to pressure Ortega and Murillo, including CAFTA.

“The business sector has to understand that doing business within Nicaragua is going to have more and more cost, and that decisions are going to be marked by this,” added Núñez.