March 26, 2023, 9:20 AM

March 26, 2023, 9:20 AM

An unknown deadly disease, a community persecuted by a ruthless invader and some brave doctors and religious.

The above looks like the list of ingredients from a Hollywood movie, but they are part of a not-so-well-known episode of World War II and eight decades will be commemorated this year.

It all happened in Rome at the end of 1943when the troops of Nazi Germany took the Italian capital after the overthrow of their ally, the fascist Benito Mussolini, at the hands of a group of soldiers, businessmen and politicians.

After seizing the “eternal city”, Adolf Hitler’s soldiers began a manhunt against the jewish community from the citywhich until then had been saved from the brutal persecution and annihilation recorded in other areas of Europe.

To avoid being deported to the feared concentration camps, of which information had begun to arrive, many Jews took refuge with neighbors, but above all in churches, monasteries, convents and even in hospitals administered by the Church C.atolic.

In one of those health centers, three doctors welcomed dozens of people and diagnosed them with a terrible and deadly disease, of which no one had ever heard of. And it could not be different, because the disease never existed.

An original and dangerous remedy

On October 16, 1943, the Italian capital woke up with a start. German soldiers poured into the Jewish ghetto, just three kilometers away from the Vatican; and they began to seize men, women, and children, capturing more than a thousand.

Some lucky ones managed to escape and arrived at the San Juan Calibita hospital, known by the Romans as Fatebenefratelli (Do good brother, in Spanish).

The center, 437 years old and belonging to the Holy See, is located on a small island in the middle of the Tiber River and from it you can see the Great Synagogue of the Italian capital and what was the Jewish ghetto.

The Nazis soon arrived at the hospital to continue their hunt. The then director of the hospital, Giovanni Borromeo, a fervent Catholic with good contacts in the Holy See, received them and offered to show the uniformed officers the compound.

However, upon reaching a room, he warned them that there were people isolated there because they presented the symptoms of a strange and dangerous disease that they were just investigating.

Borromeo told the Germans that it was the K-syndromea disease he described as highly contagious, affecting the neurological system and leading to death.

“We call it K after Commander (Albert) Kesselring (responsible for the occupation of Italy): the nazis thought it was cancer or tuberculosis and ran away like rabbits“, affirmed the doctor Vittorio Sacerdoti to the BBC in 2004.

Sacerdoti was, together with Borromeo and the Italian doctor and anti-fascist Adriano Ossicini, the intellectual author of the deception that allowed dozens of Jews to be saved from certain death.

This doctor, who he was jewish by origin he was hired by Borromeo to work in the Roman hospital, despite the fact that the racial laws approved by Mussolini in the late 1930s outlawed this.

There are also versions that ensure that the K with which the fictitious disease was baptized was also for Herbert Kappler, head of the feared SS in Rome, although other experts offer different explanations.

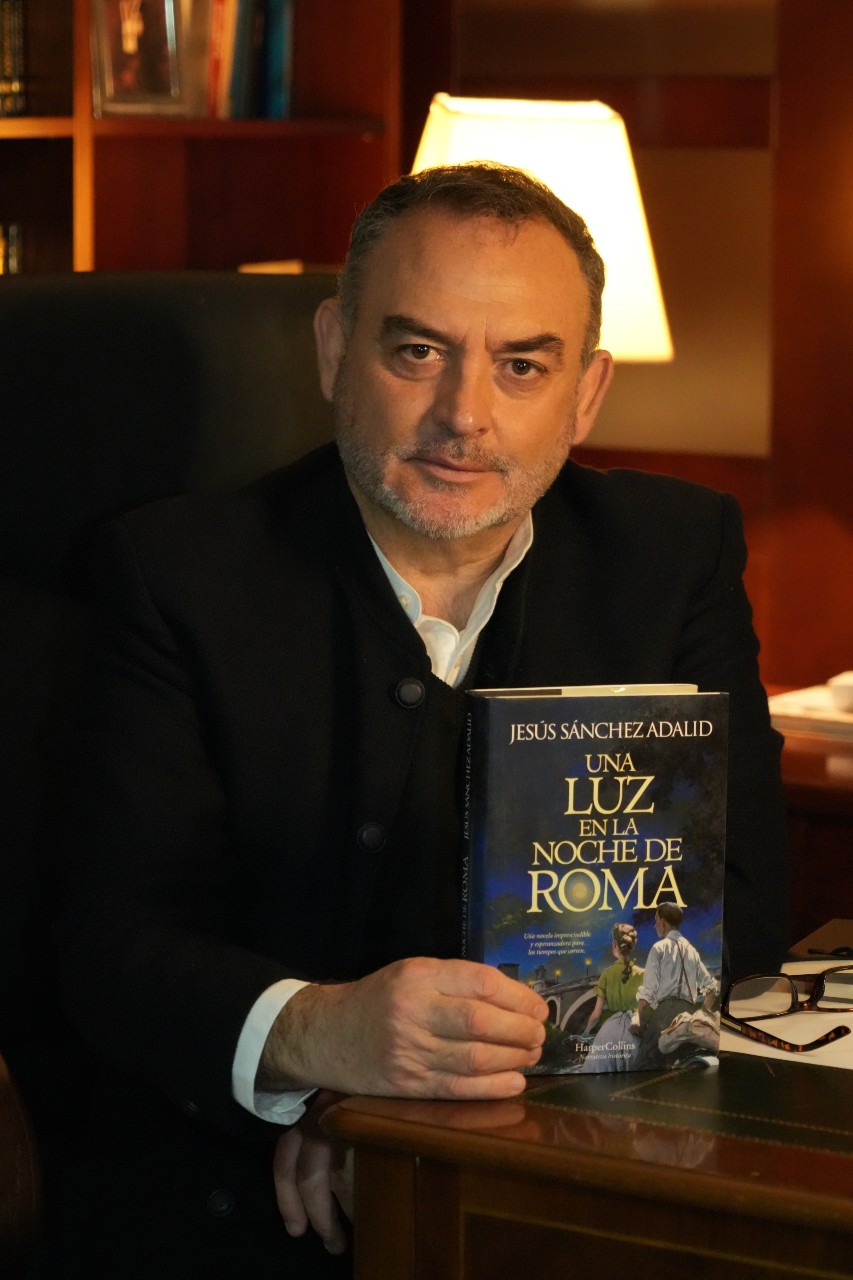

“The disease was baptized K syndrome so that making an approximation to Koch’s disease (tuberculosis) that was causing a lot of problems for Hitler’s troops in Hungary and Poland at that time,” Spanish writer and priest Jesús Sánchez Adalid explained to BBC Mundo.

Earlier this month the author published the novel “A light in the night of Rome”, a love story between a wealthy young woman and a Jewish boy, which takes place precisely during these historical events.

Borromeo, Sacerdoti and Ossicini launched a great show. Thus they began to fabricate the medical records of the Jews who had supposedly contracted the mysterious disease, an operation that required the collaboration of many people inside and outside the center.

“There was a very broad team that involved religiousincluding the superior of the order (San Juan de Dios) who administered the hospital,” added Sánchez Adalid.

Other historical and journalistic investigations indicate that Monsignor Giovanni Battista Monti, the future Pope Paul VI and who at the time held a high position in the Vatican Secretariat of State, was aware of what was happening in the hospital and supported him. The then prelate signed several documents that facilitated Borromeo’s activities.

And although the version of the alleged lethal disease kept the Nazis at baythe doctors did not lower their guard and instructed the Jews on what to do in case they returned.

“The doctor had told us that if the Germans came we had to cough with all our might and give the impression that we were terminally ill“, declared in 2019 to the german public televisionGabrielle Soninno, who was barely four years old when she was “admitted” to the Catholic hospital.

And the Nazis bought that story? “The Germans sent doctors to the hospital to corroborate the version of the disease, but they were satisfied with the explanations of the Italian doctors. Capable the fear of getting infected or the simple fact of not wanting to waste time in a hospital full of patients made them fall into deception”, explained Sánchez Adalid.

“If the German doctors had examined the alleged patients, they would have discovered the liebut they did not do it”, finished off.

In May 1944, the Nazi troops returned to the hospital and inspected it, but when they passed the room where the Jews were isolated and heard them cough, they passed by.

A month later the allied forces liberated Rome and the assumptions remaining patients in the hospital were discharged.

The events that occurred in the Roman hospital have been corroborated by historians and different authorities.

Thus, the Yad Vashemthe Holocaust remembrance center in Israel, awarded Borromeo in 2004 the distinction, post-mortem, of “right among the nations”an honor reserved for those people who saved or helped save Jewish lives during World War II.

How many lives did Syndrome K take from the Nazis? That remains unknown.

“We do not know the exact number of people saved in the hospital. We have not been able to get it, because the hospital was an escape bridge,” explained Sánchez Adalid, who spent two years researching the archives of the center to write his novel, in which Vatican, as well as in the Shoa Foundation and Yad Vashem itself.

“To the people who arrived at the Fatebenefratelli, supposedly sick, they gave them false documentation so they could go to Switzerland or other countries. At one point there were 75 children,” said the novelist and religious.

Sánchez Adalid revealed that some of the “patients” ended up emigrating to Latin America after the war ended, although he refused to give information about them, alleging that they wish to remain anonymous.

The hospital was just one of the places with which the Catholic Church saved Jews from extermination in Europe.

“The Church saved 4,480 Jews that we know of in this hospital, in churches, monasteries and convents,” said Sánchez Adalid.

“I have been told that when the Gestapo arrived in Rome they were surprised to see that in some convents there were up to 70 nuns, many of them were not nuns, but jews in disguise, of course. The nuns invented crazy explanations to distract the Nazis, such as that since Rome is the capital of Catholicism, it is obviously where there are the most nuns,” he pointed out.

The protection that the fictitious disease offered allowed the hospital to not only serve as a refuge for Jews.

“Thanks to the fear that the Nazis seized, the hospital was an espionage center, a communications base and a meeting place for the Italian resistance,” said Sánchez Adalid.

In the Fatebenefratelli the so-called Victoria radio operateda communications network operated by American soldiers of Italian descent that relayed to the Allies where Nazi units and barracks were in Rome to be bombed.

The writer and religious assured that he did not seek to write “A light in the night of Rome” for the 80th anniversary of the events that occurred in the Roman hospital, but that the story was offered to him by the authorities of the center.

However, Sánchez Adalid admitted that his research allowed him to confirm that “in the worst moments in human history is when the best of the human being comes out and sprouts.”

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.