II

Almost a decade after January 1959, the tension between heterodoxy and orthodoxy would be one of the distinctive features of the Cuban panorama. 1968 was a key year in that sense.

Precisely because of its heresies, the Soviets viewed the Cuban process with mistrust and suspicion, or at most as it was from the very beginning: a work of petty-bourgeois bearded boys who had to be guided along the true path. guerrilla focus vs. mass struggle. Voluntarism vs. centralized planning. socialist realism vs. plurality. On this last point, inSocialism and man in Cuba” (1965) Che Guevara had written against any possible tropical Zhadonovism:

In countries that went through a similar process [se refiere a los de Europa del Este, A.P.] it was tried to combat these tendencies with an exaggerated dogmatism. General culture became almost a taboo and a formally exact representation of nature was proclaimed the summum of cultural aspiration, later becoming a mechanical representation of the social reality that was wanted to be seen; the ideal society, almost without conflicts or contradictions, that they sought to create….

So simplification is sought, what everyone understands, which is what officials understand. Authentic artistic research is annulled and the problem of general culture is reduced to an appropriation of the socialist present and the dead past (therefore not dangerous). This is how socialist realism was born on the basis of the art of the last century.

Concluding the following:

It is not intended to condemn all forms of art subsequent to the first half of the 19th century from the pontifical throne of extreme realism, as it would fall into a Proudhonian error of returning to the past.

At that time, something was happening in Cuba that almost nobody remembers today: the simultaneous construction of socialism and communism in three small rural towns: San Andres de Caiguanabo, in the Guaniguanico mountain range, Pinar del Río; Banao, in Las Villas; and Great Earth, in the East. A concrete way of positioning oneself against orthodoxy and an expression that utopia was attainable by other means, far from any Eurocentrism. “Naturally,” observes a studious- “In that trial of communism, the State did not cede its functions to society, but on the contrary, it concentrated them all.”

On the other hand, according to Raúl Castro, towards the end of 1967, the Cuban leaders had in their possession “information coming from various sources, all of it reliable, which led us to suppose the existence of a current of ideological opposition to the Party’s line. […]. This current did not come precisely from the enemy ranks, but from people who moved within the ranks of the Revolution, acting from supposed revolutionary positions”.

That is what explains the arrest of more than thirty former militants of the Popular Socialist Party, led by Aníbal Escalante (1909-1977), former lawyer of the sugar leader Jesús Menéndez, former editor of the newspaper Today and a member of the Central Committee, who in 1962 had been relieved of his duties in the process of forming the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI) during the fight against sectarianism.

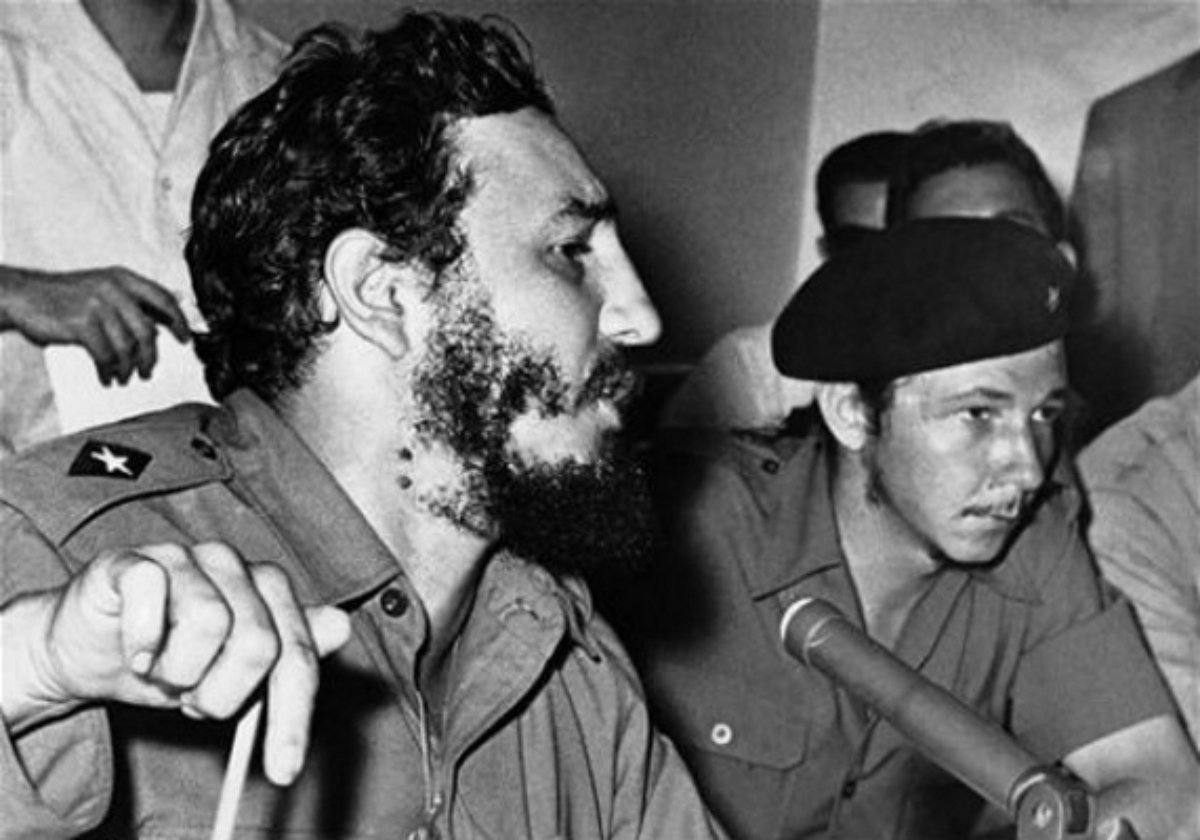

The process against the microfraction was underway in January 1968 while Fidel Castro was speaking to the intellectuals at the closing of that Cultural Congress in Havana. The list of objections and criticisms of the micro-fractionalists to the guerrillas of the Sierra were practically the same as those marked by Soviet officials: from economic issues such as the lack of knowledge of the law of value and the budgetary financing system, to the excess of volunteer and unpaid work. Nor were the problems of foreign policy left out, especially support for the guerrillas and the training of Latin American combatants in western Cuban highlands.

Two months later, in March 1968, on the university steps of San Lázaro y L, Fidel Castro would speak out for the second time against the Soviet manuals, in a position with the young professors of the Department of Philosophy of the University of Havana, also managers /editors of Critical thinking (1967-1971), one of the magazines that summarizes the spirit of that entire time.

He then alluded to the “abyss, the enormous abyss that sometimes mediates between general conceptions and practice, between philosophy and reality.” And he also said: “the manuals they have become outdated, they have become something anachronistic, because they are not able to say a single word on many occasions about the problems that the masses should know about”.

Backed by the Warsaw Pact, but opposed by Romania and Albania, on August 20, 1968, the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia. On Friday, August 23, three days after the tanks entered Prague, Fidel Castro appeared on television in which he supported the action: “We accept the bitter necessity of sending forces to Czechoslovakia and we do not condemn the socialist countries that made that decision,” he said.

Obviously a twist, but:

We wonder if in the future relations with the communist parties will be based on their positions of principle or will continue to be dominated by unconditionalism, satelism and lackeyism and will only be considered friends those who unconditionally accept everything and are incapable of absolutely disagreeing with any.

And with several additional questions, all provocative:

Will the divisions of the Warsaw Pact also be sent to Vietnam if the US imperialists increase their aggression against that country and the people of Vietnam ask for that help? […]. Will Warsaw Pact divisions be sent to Cuba if the Yankee imperialists attack our country, or even, in the face of the threat of an attack by the Yankee imperialists on our country, if our country requests it?

The famous “critical support” that scholars of the period speak of. “The KGB believed that Castro would support the protest movement of the Czechs to score points against the USSR, but to his surprise, the Cuban leader condemned the liberalization movement” [de los checos, la Primavera de Praga, A.P]write one Russian academic.

Not only the KGB but also the national public opinion. Testimonies of the time assure that the people in the streets expected a condemnation of the invasion due to certain obvious similarities: a small country saw its sovereignty violated by one that was too large. There was indeed a current of empathy towards the Czechs, not only for heretics and little ones, but also for their films – for example, the musicals Waltz for a million Y love is harvested in summer or the parody of the old West in lemonade joe—for the rock and jazz records that were sold at the Casa de la Cultura Checa, at 23 y O, and even for a beer tavern located at San Lázaro y N.

But the arrow had been released. The hour of institutionalization was already arriving.

To be continue…