July 27, 2022, 8:23 AM

July 27, 2022, 8:23 AM

Thirty years ago, a bold plan was cooked up to persuade the public that climate change was not a problem.

A little-known meeting between some of America’s biggest industrial players and a public relations genius forged a successful strategy whose devastating consequences are all around us.

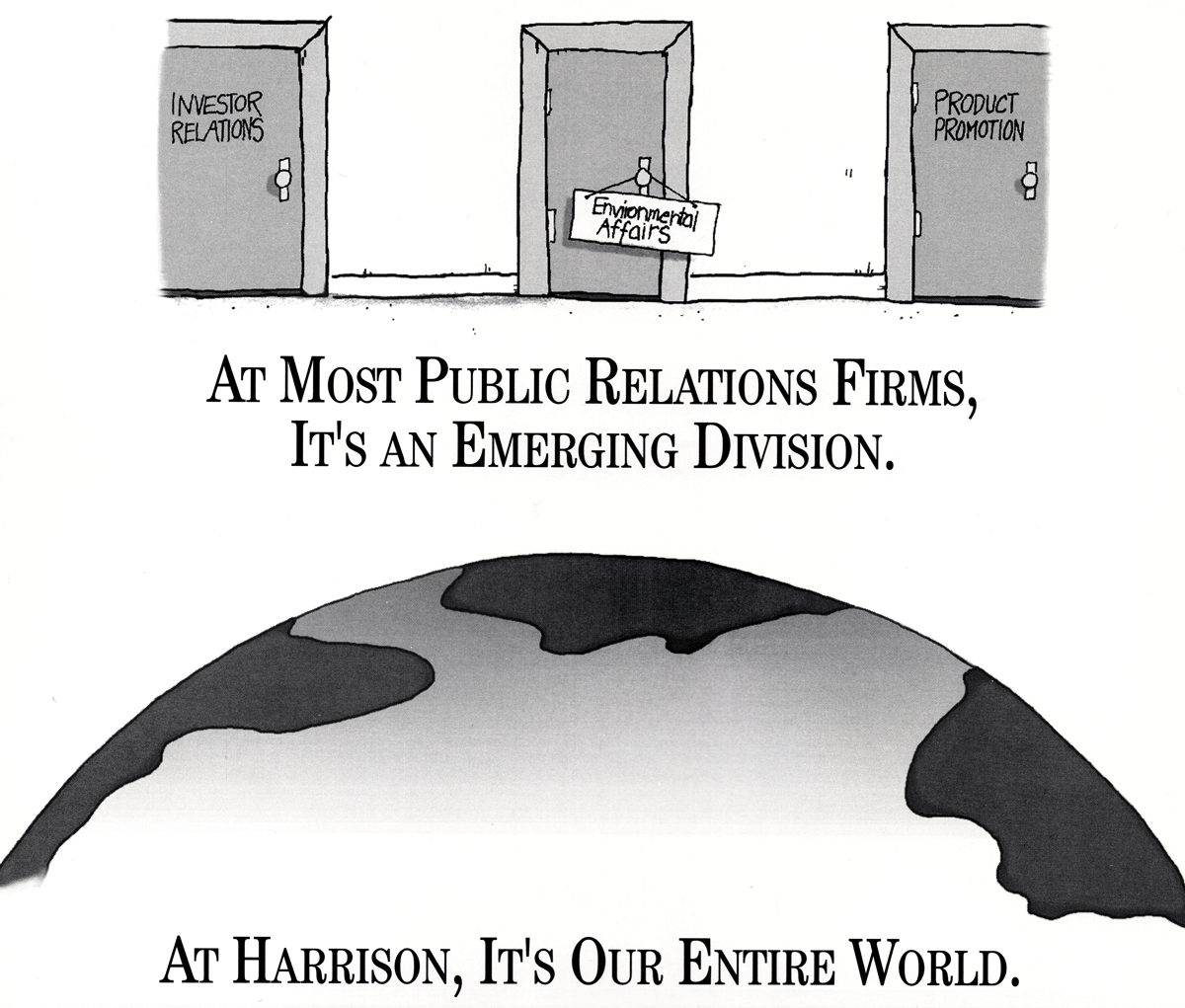

In the early fall of 1992, E.Bruce Harrisonconsidered the father of environmental public relations, stood up to a room full of business leaders and launched a proposal that has become a nightmare for environmentalists and endures to this day.

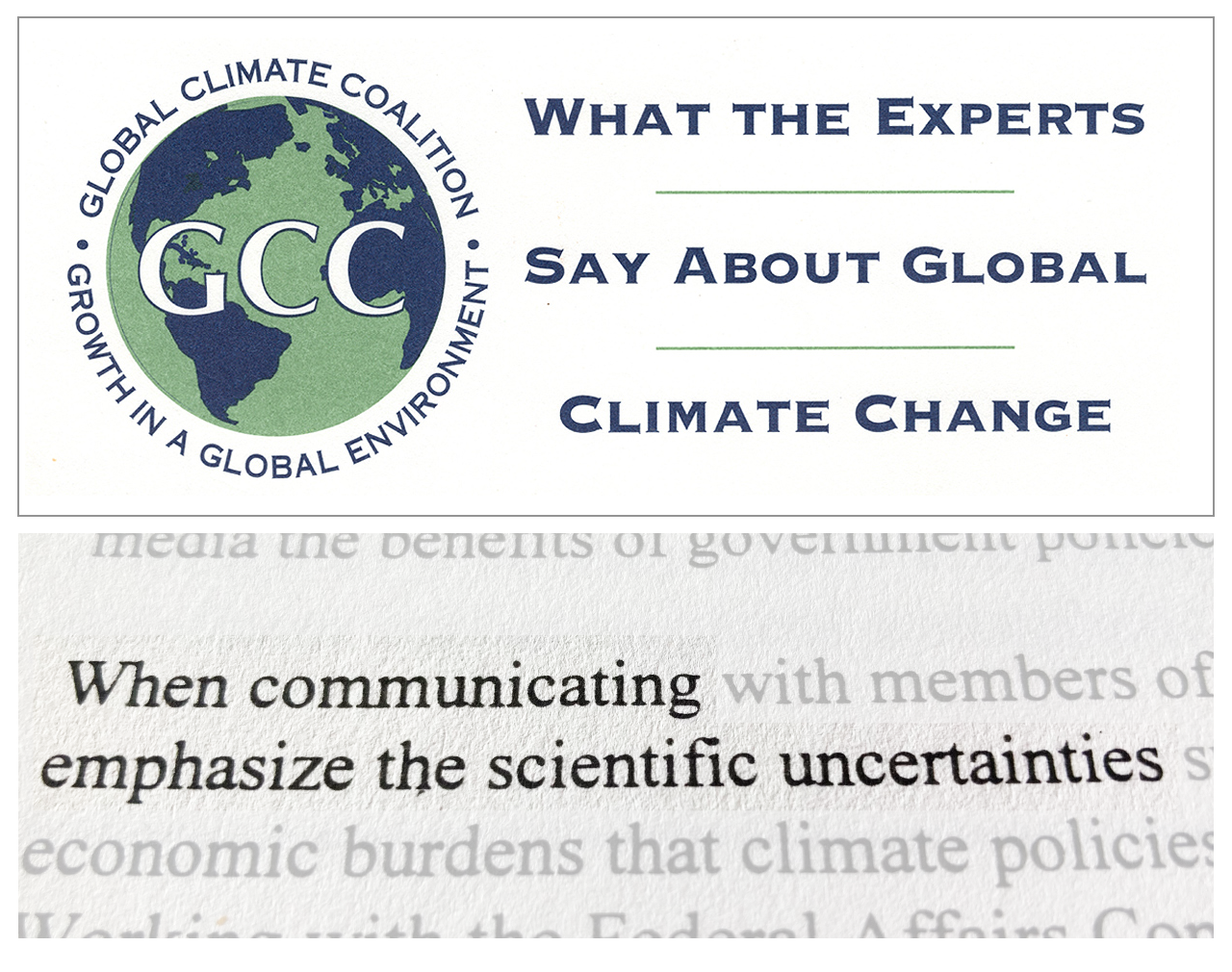

At stake was a contract worth half a million dollars a year. The client was the Global Climate Coalition (GCC), which included the oil, coal, steel, rail, and automobile industries. The group was looking for a communication partner to change the discourse on climate change.

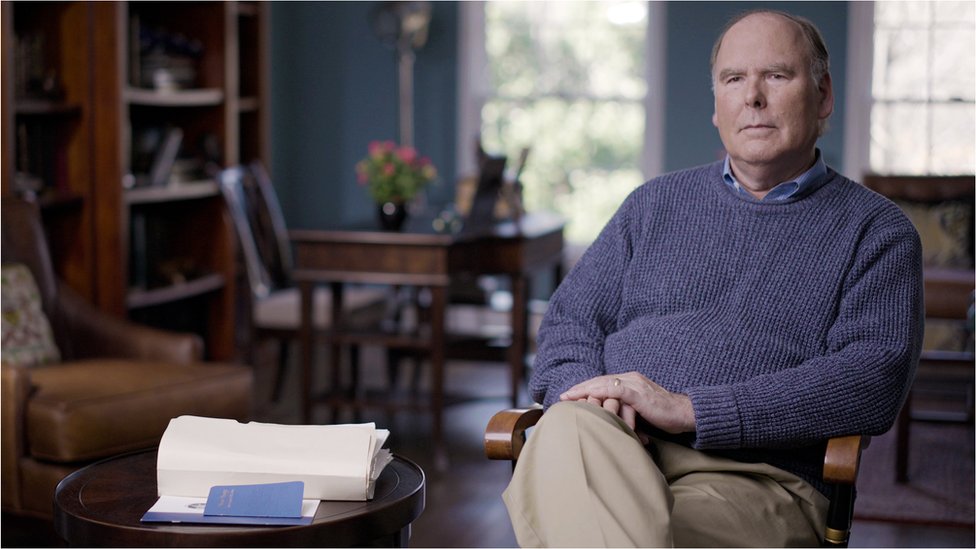

Don Rheem and Terry Yosie, two of Harrison’s team members present that day, shared their stories with the BBC for the first time.

“Everyone wanted to get their hands on the Global Climate Coalition account,” Rheem recounted, “and there I was, right in the middle.”

Changes of winds

The GCC had been conceived just three years earlier as a forum for its members to exchange information and pressure policymakers to stop efforts to reduce fossil fuel emissions.

Although scientists were rapidly advancing their understanding of climate change, and its importance on the political agenda was increasing, in its early years the Coalition was unconcerned. In the White House was George Bush Sr., a former oil businessman, and, as a senior member of the group told the BBC in 1990, his message on the climate was the message of the GCC.

There were no regulations on the horizon that would force the reduction of polluting gas emissions.

But everything changed in 1992. In June, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the international community created a framework for climate action, and the US presidential election in November of that year brought Al Gore, a committed environmentalist, to the Vice Presidency . It was clear that the new administration would try to regulate fossil fuels.

The GCC recognized that it needed help in strategic communication and put out a tender to hire a public relations firm.

Though few outside the PR world had heard of Harrison or the company he’d run since 1973, he had a string of campaigns to his credit for some of America’s biggest polluters.

The expert worked for the chemical industry discrediting research on the toxicity of pesticides; for the tobacco industry, and had recently campaigned against the tightening of regulations that sought to limit polluting emissions produced by car manufacturers. Harrison had created a company considered one of the best.

“He was a master at what he did,” said media historian Melissa Aronczyk, who interviewed Harrison before he died in 2021.

Assembling the team

To win the GCC contract, Harrison assembled a team of public relations professionals, both experienced and novice. Among them was Don Rheem, who had no industry credentials but had studied ecology before becoming an environmental journalist.

“I thought, ‘Wow, this is an opportunity to get a front row seat on probably one of the most pressing issues of science policy and public policy that we face,” Rheem said, recalling what he thought when he received an offer to work with the GCC.

For his part, Terry Yosie, who had just been hired by the American Petroleum Institute, of which he ended up becoming vice president, recalled that Harrison began his speech by reminding the audience that he was decisive in the fight against reforms in the automobile sector. . Something he achieved by reframing the subject.

The “public relations guru” proposed a strategy to defeat those who now sought to take action in favor of the environment. The recipe included convince the public that data scientists on climate change No they were reliable and that, in addition to the environment, politicians should take into account how, according to the GCC, measures against polluting gases they would harm to jobs, trade and a prices.

The move would be carried out through an extensive media campaign, in which not only opinion pieces would be published, but journalists would be contacted directly to convince them that climate change was not a threat.

“Many journalists were struggling with the complexity of the issue. So I wrote notes so that the journalists could read them and catch upRheem admitted.

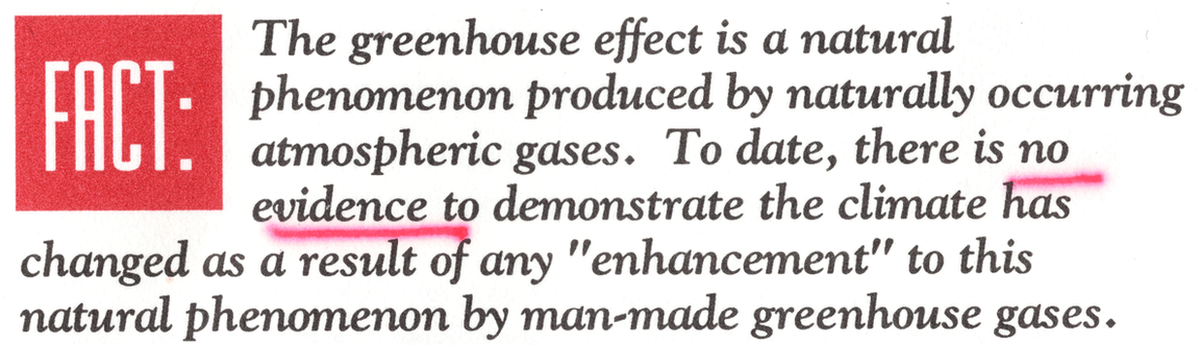

The GCC launched a wide range of publications ranging from letters, glossy brochures and monthly newsletters, questioning whether global warming was caused by industrial pollution and posing a risk. The move allowed Harrison’s company to be cited 500 times in the media in one year.

achieving the goals

In August 1993, Harrison took stock of progress at another meeting with the GCC.

“Growing awareness of the lack of corroborating scientific data has caused some in Congress to halt new initiatives”he declared at a meeting, Yosie assured the BBC.

“Activists who warn about ‘global warming’ have publicly acknowledged that they have lost ground in communication over the last year,” Harrison said on the occasion, in which advised to his clients expand the offensive by resorting to other voices.

“Reputable scientists, economists, academics and other experts have more credibility with the media and the general public than representatives of industry,” he said.

Although most scientists agreed that man-made climate change was a real problem that required action, a small group argued that there was no cause for alarm. The plan also foresaw pay these skeptics to give speeches or write op-eds -about 1,500 dollars per article- and in organizing media tours, so that they appeared on local television and radio defending their theses.

“My role was to identify the voices that weren’t in the mainstream and give them space,” admitted Rheem. “There were a lot of things we didn’t know at the time. And part of my role was to highlight what we didn’t know.“.

Rheem recalled that the media was eager to have perspectives other than those that held that we were moving toward an environmental crisis.

“Journalists actively sought out voices who were against climate change. what we did was feedsr an appetite that already existed“, he commented.

Many of these skeptics or deniers have denied that funding from the GCC and other industry groups has influenced their views. But the scientists and environmentalists who defended the existence of climate change found themselves with a campaign that was difficult for them to match.

“The Coalition sowed doubt everywhere and environmentalists didn’t really know how to respond,” recalled environmental activist John Passacantando.

“What the public relations geniuses who worked for the oil companies knew was that if you say something enough times, people will start to believe it“, he sentenced.

a disastrous victory

In a document back in 1995, which Melissa Aronczyk gave to the BBC, Harrison wrote that the “GCC has managed to turn the tide of press coverage of climate change, effectively countering the message of eco-catastrophe, thanks to the thesis of the lack of scientific consensus on global warming.

The ground had been laid for the industry’s biggest campaign to date: opposing international efforts to negotiate emission reductions in Kyoto, Japan, in December 1997. By then, there was a consensus among scientists that global warming man-made was detectable. But the American public was still hesitant.

As many as 44% of those polled in a Gallup poll believed that scientists were divided. Public antipathy made it easy for the US to never implement the Kyoto Protocol. It was a great victory for the GCC.

“I think Harrison was proud of the work he did. I knew how important it had been in changing the direction of the global warming debate,” Aronczyk said.

The same year as the Kyoto negotiation, Harrison sold his company. Rheem decided that public relations was not the right career path, while Yosie moved on to other environmental projects. Meanwhile, the GCC began to disintegrate, as some members grew uncomfortable with its hard line. But his tactics and, above all, doubts were already entrenched and would outlive their creators. Three decades later, the consequences are all around us.

“I think it’s the moral equivalent of a war crime,” Former Vice President Gore asserted about the efforts of the big oil companies to block any type of legislation and measures in favor of the environment and against pollution.

“I am convinced that, in many ways, it is the most serious crime since World War II. The consequences of what they have done are almost unimaginable.“, added who aspired to the Presidency of the United States. in the year 2000.

“Would you do anything different? It’s a difficult question to answer,” admitted Rheem, who justified himself by saying that he was “very low” in the chain of command of the GCC.

However, he insisted that climate science was too uncertain in the 1990s to warrant “drastic action” and that developing countries – notably China and Russia – have been ultimately responsible for decades of inaction in matter climaticand not the American industry.

“It’s very easy to create a conspiracy theory about the industry’s really pernicious intent to stop by any regulation. Personally, I didn’t see that,” he said, adding: “I was very young… Knowing what I know today, would have done some things differently? Maybe, probably.”

Now you can receive notifications from BBC World. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.