April 15, 2023, 10:07 AM

April 15, 2023, 10:07 AM

When Russia invaded the Ukraine, a second and less visible battle in cyberspace started. Joe Tidy, the BBC’s cyber affairs correspondent, traveled to Ukraine to speak to those who are fighting cyber warfare.

He found that the conflict has blurred the lines between cybermilitary and ‘hacktivist’ activities. This is the report of him in first person.

When I visited Oleksandr in his one-bedroom apartment in central Ukraine, I found a setup typical of many hackers.

No furniture or amenities, not even a television. Just a powerful computer in one corner of his bedroom and a powerful music system in the other.

From here, Oleksandr helped temporarily disable hundreds of Russian websites, disrupted services at dozens of banks and vandalized websites by writing pro-Ukrainian messages.

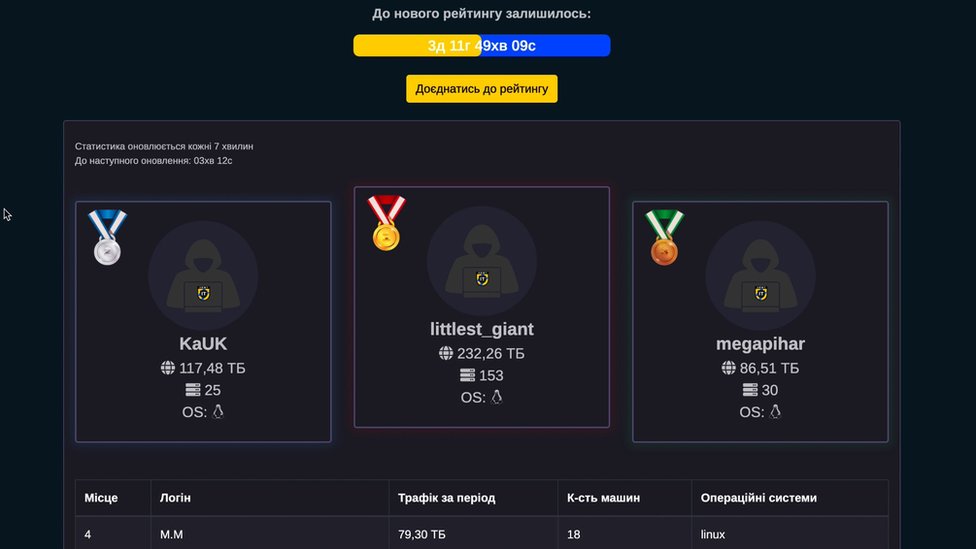

Is one of the most prominent hackers in the Ukrainian IT Army vigilante groupa volunteer hacking network with a Telegram group of nearly 200,000 users.

For more than a year, Oleksandr has set out to cause as much chaos as possible in Russia.

Even during our visit, it was running a complex program trying to take a Russian banking website offline.

Ironically, he admits that your favorite hack started with a hint given to him by an anonymous Russian.

“Someone from Russia told us about an organization called Chestny Znak,” he explains.

“They said it’s the only system Russia product authenticationSo every product, from manufacturing to selling, must be scanned for a unique number and company-provided barcode,” he says.

Oleksandr smiles as he describes how, together with his team, found a way to disconnect the service.

He used an attack known as denial of service (DDoS), a hacking tool that floods a computer system with internet traffic to force it to go offline.

“I think that economic losses were quite large. It was amazing”.

It’s actually hard to gauge the disruption caused by that action, but for four days in April 2022, Chestny Znak posted regular updates about the DDoS attack on his Telegram.

More recently, around the anniversary of the invasion, Oleksandr joined a team of hackers, called a fistto hijack Russian radio stations and broadcast the sound of fake air raid sirens alerting citizens to seek shelter.

“We feel like soldiers. I’m prepared if my country calls me to pick up a riflebut I feel useful hacking Russia,” says Oleksandr.

surprising sophistication

Many experts predicted that hackers would play their part in the Ukraine conflict, but the scale is surprising. hacker armies They emerge on both sides.

Unprecedented links are also emerging between these groups and military officials.

The lines between targeted and state-sanctioned cyberattacks and ad-hoc vigilante hacking have blurred. The consequences could be extensive.

On a visit to Ukraine’s cyber defense headquarters in Kyiv, officials say the Russian hacker gang Killnet, with a Telegram group of nearly 100,000 subscribers, works directly with Russia’s cybermilitaries.

“These groups, like Killnet or the Russian Cyber Army, started out by launching DDos attacks, but they have recruited more talent,” says Viktor Zhora, vice president of the State Service for Special Communications.

“Now they are capable of launching sophisticated cyberattacks and have consultants from the Russian army. Their commanders are uniting all these groups and activities into a single source of Russian aggression in cyberspace against Ukraine and its allies,” Zhora explains.

If proven, this link would be problematic for Russia.

Killnet has carried out disruptive, albeit temporary, attacks on hospital websites in both Ukraine and allied countries.

Although there is no Geneva Convention for cyber warfare, the International Committee of the Red Cross argues that some existing codes could apply. attack hospitalsfor example, would be to violate those codes.

If NATO countries are attacked, this could also lead to a collective response if serious damage is caused.

The Russian government did not respond to BBC requests for comment.

12 hours a day dedicated to hacking

Instead, we go to the Killnet leader, who goes by the nickname killmilk.

He first declined a face-to-face interview, but after weeks of Telegram messages, he sent answers to our video questions. Then he cut off communications.

“We spend 12 hours a day on Killnet. I don’t see the same in the world to Russian hackers. Useless and stupid Ukrainian hackers can’t win against us,” says Killmilk.

The hacker insisted that his group is completely independent of the Russian special services, stating that he works as a loader in a factory and that he is “a simple person.”

He says he started a criminal DDoS business for hire before the war, but when the invasion began he was determined to dedicate his hacking efforts against Ukraine and its allies.

“I always carry my laptop and everything I need with me. In this I am agile, efficient and dedicate almost all my time to our movement,” he says.

While groups like the Anonymous collective have slowed down their activities in the past three months, Killnet has picked up speed, buoyed by bombastic videos of Killmilk urinating on US and NATO flags.

Over the Easter weekend, the Killnet Telegram channel was used to create a team called KillNATO Pshychos (Kill NATO Psychopaths).

Within hours he had hundreds of members and launched a wave of attacks that temporarily took NATO websites offline. The group also published an email list of NATO workers and incited people to harass them.

Allegations that Russian cybermilitaries are collaborating with criminal hackers come as no surprise to many in the cybersecurity world, who for years have accused Russia of hosting some of the world’s most prolific and lucrative cybercrime groups.

Fuzzy connections, also in Ukraine

Our visit to Ukraine confirmed that collaborations there are also diffuse.

A year ago, as the capital of Kyiv prepared to attack, Roman helped launch criminal hacks and design war programs as part of a volunteer group he founded called IT Support Ukraine.

In recent months, Roman has been officially recruited by his country’s cyber army.

We meet in a park near their training headquarters in the city of Zhytomyr, two hours west of Kyiv.

Roman has unique perspectives.

He doesn’t offer details about his current role, but says part of his job is to find ways to analyze reams of data and leaked information from cyber warfare.

Even before being recruited, Roman confirms that his team worked directly with the Ukrainian authorities.

“We began to communicate with the state forces that were doing the same as us and we began to synchronize our operations. Basically they began to dictate objectives, what to do and when,” he says.

One of the most impactful jobs that Roman and his team have done was disabling ticket machines on a train network in southern Russia.

When asked about what that meant for everyday people in Russia, Roman shrugs.

It’s the kind of attack that Ukrainian cybermilitaries could never carry out publicly.

“There are no right or wrong ways to fight”

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine presents itself as the one that defends and not the one that attacks.

Mykhailo Fedorov is Deputy Prime Minister of Ukraine and Minister for Digital Transformation. His department controversially created the Ukrainian Army IT Telegram group. Since then, the government has claimed not to be involved in the hacktivist network.

Fedorov denies allegations that he motivates attacks against Russian civilian targets.

But he confidently asserts that Ukraine has “the moral right to do everything it can to protect the lives of its citizens.

“I believe that after a year of large-scale war, Ukrainian hackers have shown that, despite the invasion, they operate ethically enough and do not cause excessive damage to any subject beyond those involved in the war in the Russian Federation” , says.

However, Ukrainian hacktivists are not only attacking the Russian war machine. The hacks are organized to cause as much trouble as possible for the Russian people.

One of Ukraine’s Army IT coordinators, Ted, proudly displays his collection of angry comments from Russian clients who have experienced problems due to his activities.

I asked him about the danger of an escalation.

“We need to understand that When war comes to your country, there are no right or wrong ways to fight.”reply.

The dangers of an escalation

Some predict that the severity of these attacks will only increase in this second year of war.

Ukrainian officials say the worst attacks come not from hacktivists, but from Russian military coordinating cyber attacks and physical attacks against targets such as power grids.

Zhora says Russia has so far failed to pull off the kind of cyberattacks experts feared, but has tried.

“Of course, the impact of cruise missiles is much greater than that of cyber attacks, but the reason that the latter are not doing as much damage to the Ukrainian infrastructure is also due to our cyber defense.”

“If we were weaker, the attacks would cause more trouble.”

Cyberwar in Ukraine is assisted by Western cybermilitaries and private cybersecurity companies, financed with millions of dollars donated by their allies.

However, some people have suggested that the country has been hit harder than its commanders admit.

As with all aspects of warfare, reality is hard to penetrate, and that’s especially true in cyberspace.

Additional reporting by Peter Ball.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC News World. Download our app and activate them so you don’t miss our best content.