April 20, 2024, 10:40 AM

April 20, 2024, 10:40 AM

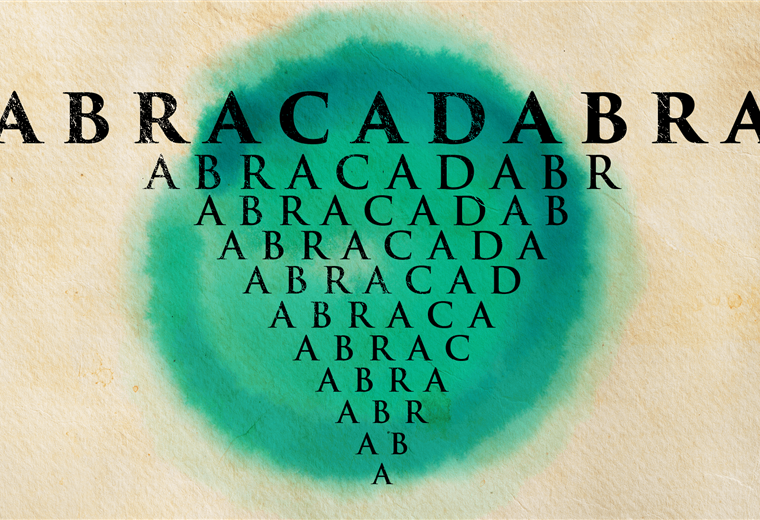

Abracadabra is a peculiar word.

Maybe you don’t remember exactly when you first heard it, but it was probably in your childhood.

Perhaps, it was introduced to you as a magic word when you were just learning what magic was; You soon understood that as soon as it was spoken something unexpected would happen: things appeared or disappeared, changed shape or color or moved on their own.

Without being an everyday word, it stuck in your mind, like that of countless children around the world, since it is part of the vocabulary of so many languages that have been said to precede the biblical Tower of Babel.

What surely no one told you was what it meant… because no one knows for sure.

If you consult the Dictionary of the Royal Academy, for example, it tells you what it is, but not what it means: “Kabalistic word to which magical effects are attributed.”

And that is not the only enigma.

As the prestigious Oxford English Dictionary points out from its first edition in 1884, the origin of the word abracadabra is “a stranger”.

That has not prevented experts from trying to unravel the mystery over the centuries, developing numerous theories.

From the Bible to a constellation

Several conjectures place the origin of abracadabra at the beginning of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

The esoteric word could be derived from a Hebrew-Aramaic phrase avra gavra, which, according to the Old Testament, was what God said on the sixth day: “I will create man”.

But that’s just one of the possibilities..

Another says that perhaps it comes from Aramaic avra c’dabrah or from Hebrew open kedobarWhat do they mean “I believe with the word” either “it happened just as it was said“.

It is “a Talmudic maxim that expresses the belief that speech has the power to cause the world to exist,” explained Alan Lew in his book “This is real…” (“This is real…”).

So the mere act of saying a word or naming something can instigate its creation.

Other experts also believe that abracadabra comes from Aramaic and Hebrew, but they consider that the meaning is completely different, such as“disappears like this word“ (abhadda kedkabhra) either “throw your lightning to death“(abreq ad habra).

There are more searches for meaning that follow the hypothesis that abracadabra comes from those Semitic languages, but also others that take different routes.

Among the many collected by Criag Conley in the book “Magic Words: A Dictionary”, is the one that maintains that Abracadabra was the supreme deity of the Assyrianseven the one that says it is a corruption of the name of the father of algebraAbu Abdullah abu Jafar Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, the 9th century Arab mathematician.

Or even that abracadabra is a phrase formulated by ancient astronomers to describe the constellation of Taurus, as stated by the astronomer Samson Arnold Mackey in 1822.

We could continue, but in the end there is nothing more than debate without consensus because, as the Oxford English Dictionary states, “no documentation has been found to support any of the various conjectures.”

However, abracadabra is one of those words that became “unintelligible to the heirs of the tradition, often ignorant of its original meaning and language,” as scholar Joshua Trachtenberg noted, ended up being a virtue.

“It is so little necessary for the magic word to possess any intelligible meaning that most of the time it is considered effective to the extent that it is strange and meaningless, and words from foreign and incomprehensible languages are particularly preferred,” wrote the academic Benno Jacob in “Im Namen Gottes” (“In the Name of God”).

Thus, exotic and meaningless, but more powerful for that reason, Abracadabra has been present in history for centuries.

And a lot was always expected of her.

transcendental power

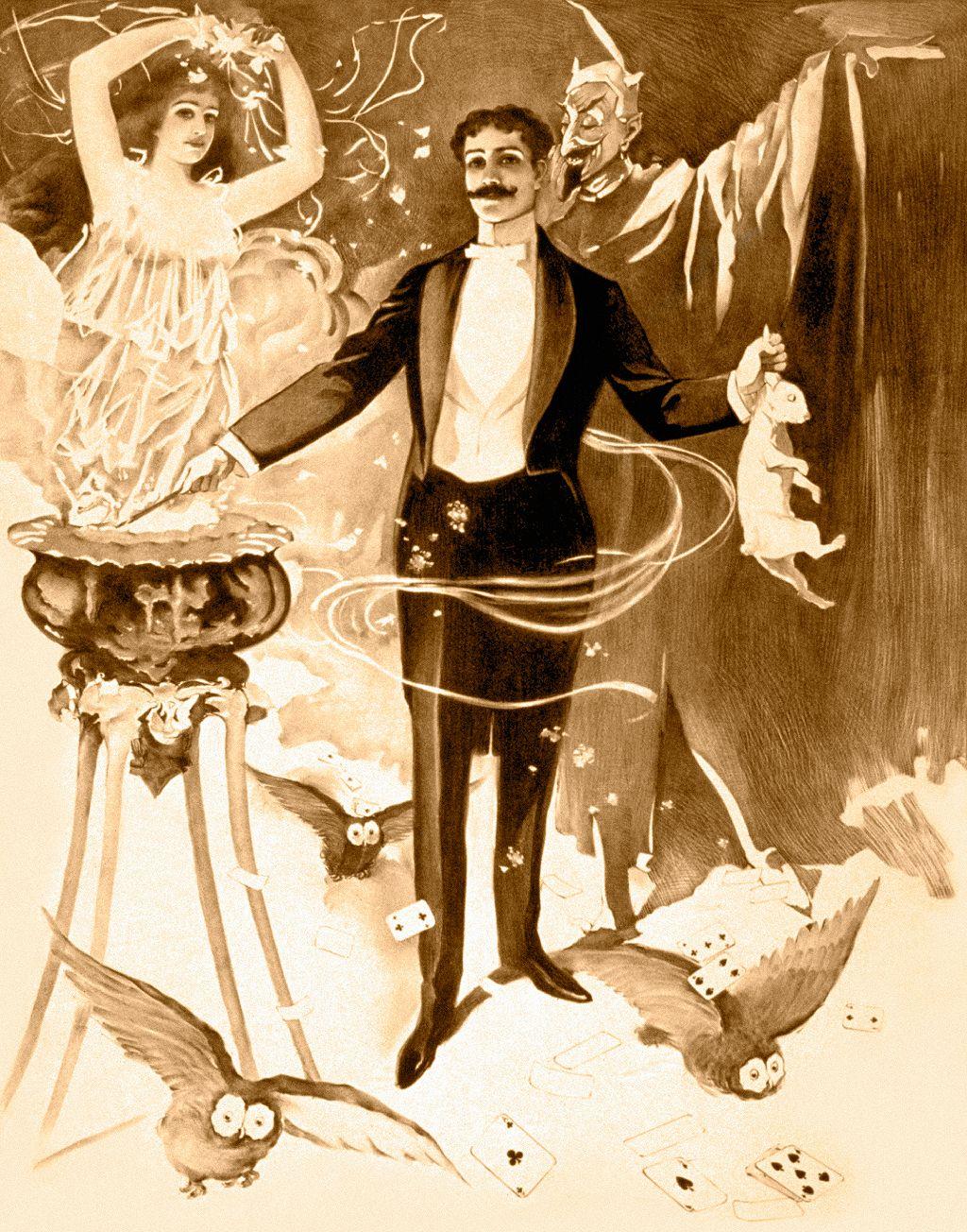

Long before it was used to make rabbits appear in empty top hats, hocus-pocus was used for more mundane things, such as scaring away demons and death, and dealing with illness.

Its first known use appears in the fragments that have survived to this day from the “Liber medicinalis” from the 3rd century AD (also known as “From Medicine Praecepta Saluberrima“).

It is the work of Sereno Sammónico, about whom not much is known but he was considered wise and was doctor to the Roman emperor Caracalla.

Among the treatments, remedies and antidotes in his book, there is one for “the deadly fever which the Greeks called ‘hemitritaion‘”.

“The word has never been translated into Latin, either because the nature of the language does not allow it or because parents, believing that doing so would be harmful to their children, have not wanted to give it a name,” wrote Sammónico.

He was referring to what we know today as malaria, which devastated ancient Rome.

To cure it, he recommended:

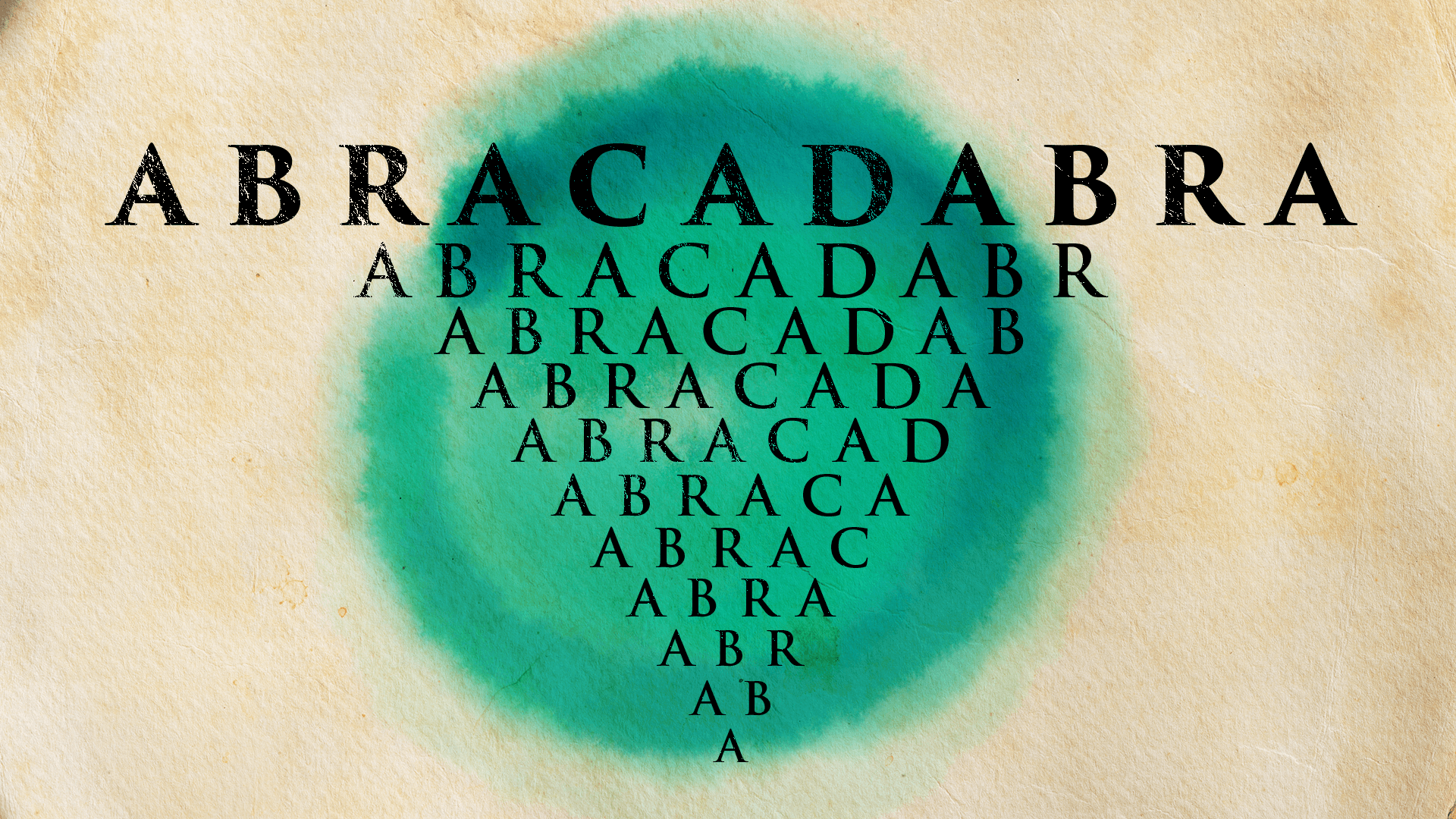

“Write on a sheet (of papyrus) the word ABRACADABRA, repeat it below, but omit the last letter, so that more and more individual letters will be missing from the lines (…) until a single letter remains as the narrow end of a cone

“Remember to tie it around your neck with a linen thread”.

The idea was that the disease would disappear like the word hocus pocus disappeared.

Sammonicus also prescribed smearing the body with lion’s fat or wearing the skin of a domestic cat adorned with jewels to protect against these fevers, but what survived was the use of the curious word, of which there are traces in various cultures and places.

It appears, for example, engraved on some of the Abraxas stones which the Basilideans, the 2nd century Gnostic sect founded by Basilides of Alexandria, used as talismans.

It was part of a magical formula to invoke the help of benevolent spirits to combat illness and have good fortune.

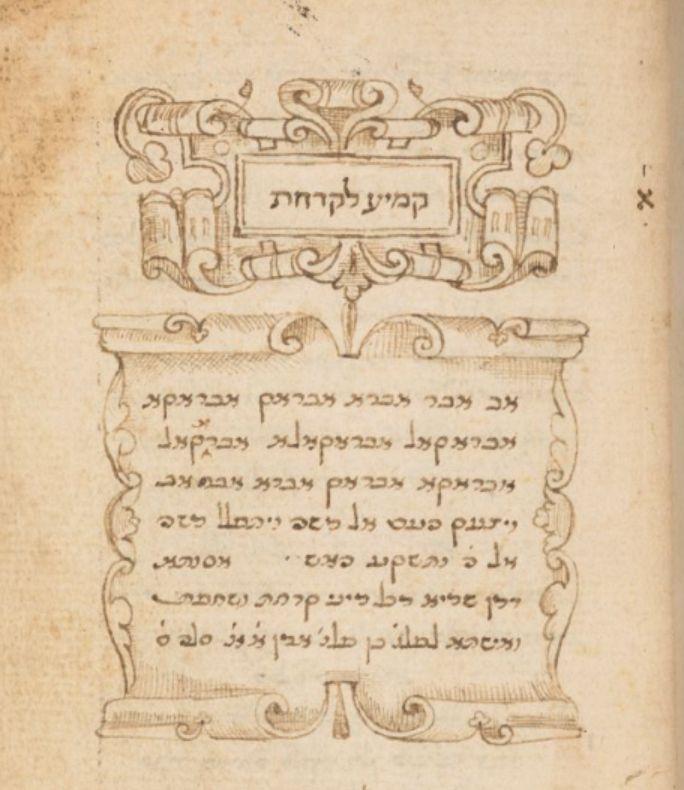

Also appears in “The tree of knowledge” (Etz ha-Da’at), a small codex written by Elisha ben Gad of Ancona in 16th century Italy.

The first of the incantations that appears in that book is a “cure from heaven” for “all kinds of fever,” and it begins by saying:

“Av avr avra avrak avraka avrakal avrakala avrakal avraka avrak avra avr av”

As in many other places, in England, well into the 18th century, hocus pocus continued to give hope for a cure, as the author of “Robinson Crusoe” Daniel Defoe noted in his book “The Diary of the Plague Year” of 1722.

He lamented that people relied on deceptions “as if the (bubonic) plague were nothing more than a kind of possession by an evil spirit,” resorting to superstitions to ward it off, including “papers tied with so many knots; and certain words or figures written on them, particularly the word Abracadabra, formed in a triangle or pyramid“.

Those who trusted in talismans still followed the instructions given centuries ago by Sereno Sammónico: they used them for nine days and then they were thrown awaythrowing them over his left shoulder before dawn into a stream flowing from west to east.

“How many poor people were later carried away on the dead carts and thrown into mass graves with those infernal charms hanging from their necks,” Defoe wrote.

There were also those who wore amulets with the pyramid pointing upwards, to attract good fortune.

At the beginning of the 19th century, with the rise of the British obsession with spiritualism, the famous English occultist Aleister Crowley decided to appropriate the magic word.

He reconstructed abracadabra through a cabalistic reformulation as “abrahadabra” in his work “The Book of the Law”, in which he outlined the basic principles of his new religion, Thelema.

According to him, abracadabra was “the Word of the Aeon, which means The Great Work accomplished.”

By then, the word had been losing its supposed healing power, but at the same time it had been acquiring another, as it was incorporated by magicians into their repertoires.

Thus, as if by magic, from the early 1800s, abracadabra became that incantation that we have known so many since we were children.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.