I have had the opportunity to visit some of the most famous museums in the world: imposing rooms where masterpieces of art history hang, modern temples where humanity keeps its memory in pigments and canvases. One hopes to leave there with one’s gaze impregnated with colors, shapes and emotions. But what remained etched in my retina were not the masters’ brush strokes, but the crowding of visitors with their phones raised, elbowing each other for the best angle for a selfie.

Entering a room where a universal work hangs—it doesn’t matter if it is a Monet, a Velázquez or a Da Vinci—is to immerse yourself in a strange collective ritual. The solemn silence one imagines is broken by the incessant hum of digital gunshots. The bodies are no longer arranged to contemplate, but to “enter the frame”: not as observers, but as protagonists. And the works, paradoxically, disappear behind the screens that replicate them in thousands of identical photos.

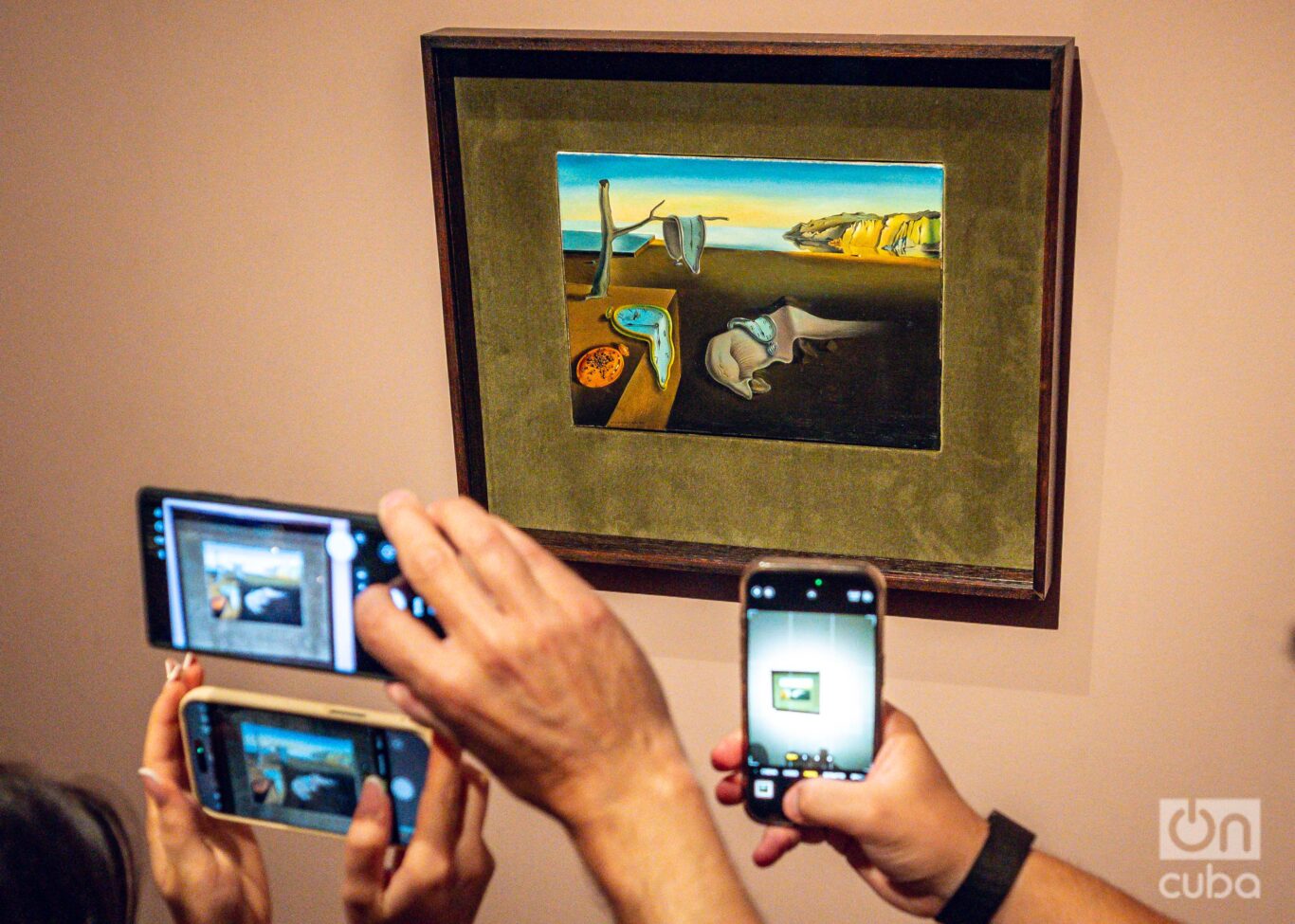

Recently, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA), I encountered a compact crowd in front of The persistence of memorythe famous painting by Salvador Dalí, also known as The soft watches.

The scene had something grotesquely surreal: the tumult of bodies and cell phones turned the contemplation of a work born from a dream into a nightmare. Nobody stayed more than a second in front of the painting.

The discreet pushes, the measured elbows, followed one another as part of an unwritten script. Whoever managed to make their way to the front row barely managed to pose, shoot the selfie and leave in a hurry, leaving behind a space that was immediately occupied by another visitor. The ritual was completed seconds later, when the photo immediately went up on social networks.

I wondered what Dalí would have said about all this. Perhaps he would have laughed with his mustache twisted, proclaiming that this was the greatest happening mass surrealism ever seen. Or perhaps he would be horrified to see how his work, designed to challenge time and dreams, is reduced to wallpaper for the instant cult of selfie.

In the midst of the whirlwind, the painting seemed to resist. There they were, unperturbed, their watches melting in an arid landscape, reminding us that time—that which is not even enough to look at a painting for two seconds—inevitably slips through our fingers.

It wasn’t the first time I experienced it. In front of a Van Gogh, I could barely stop for a few seconds: a wall of outstretched arms and cell phones prevented me from contemplating it calmly. In another room, in front of a classical sculpture, a group took turns posing, smiling, without even looking at the piece that served only as scenery. The sacredness of the encounter had dissolved in the rush to collect evidence of having been there, rather than experiences of having looked.

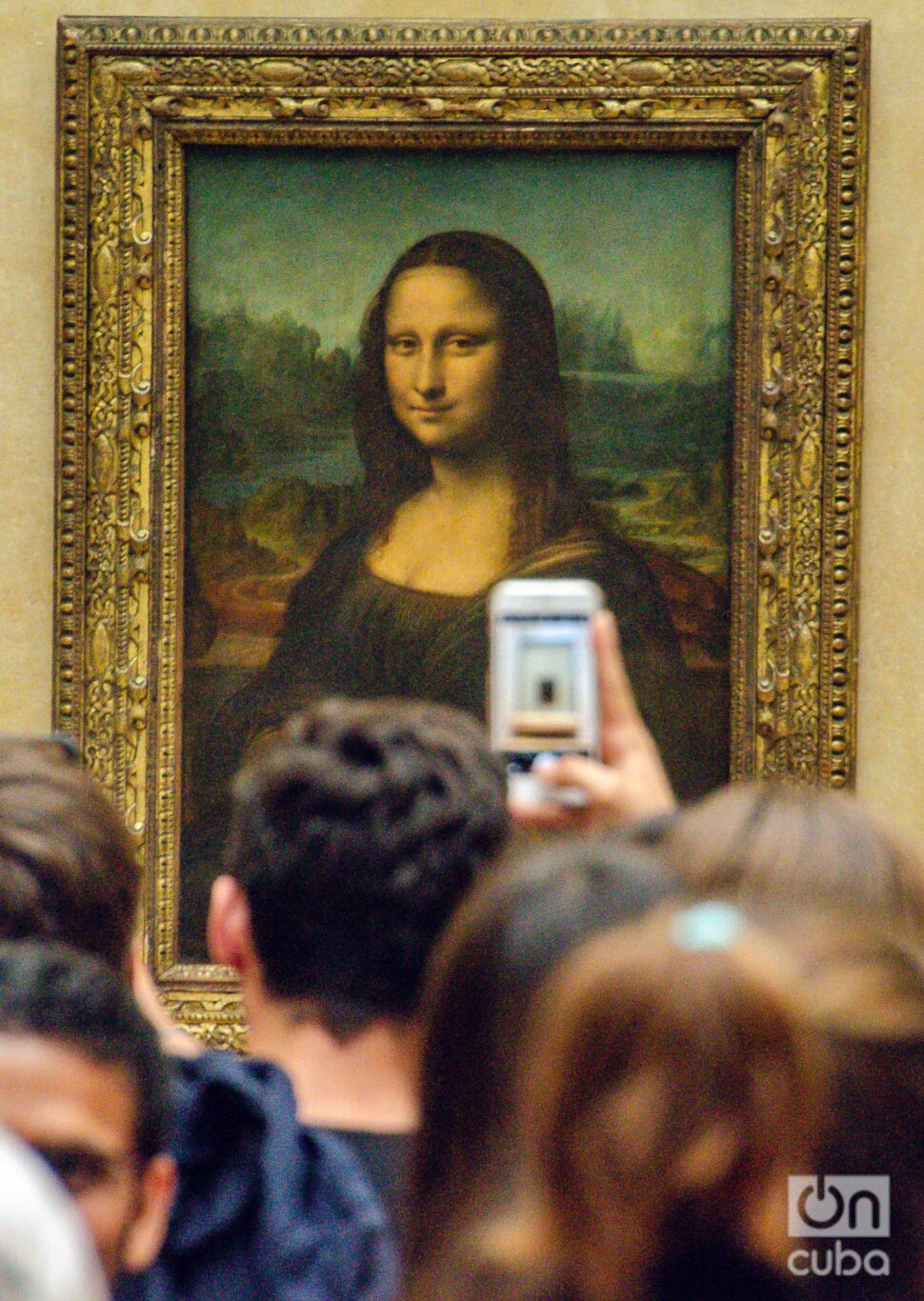

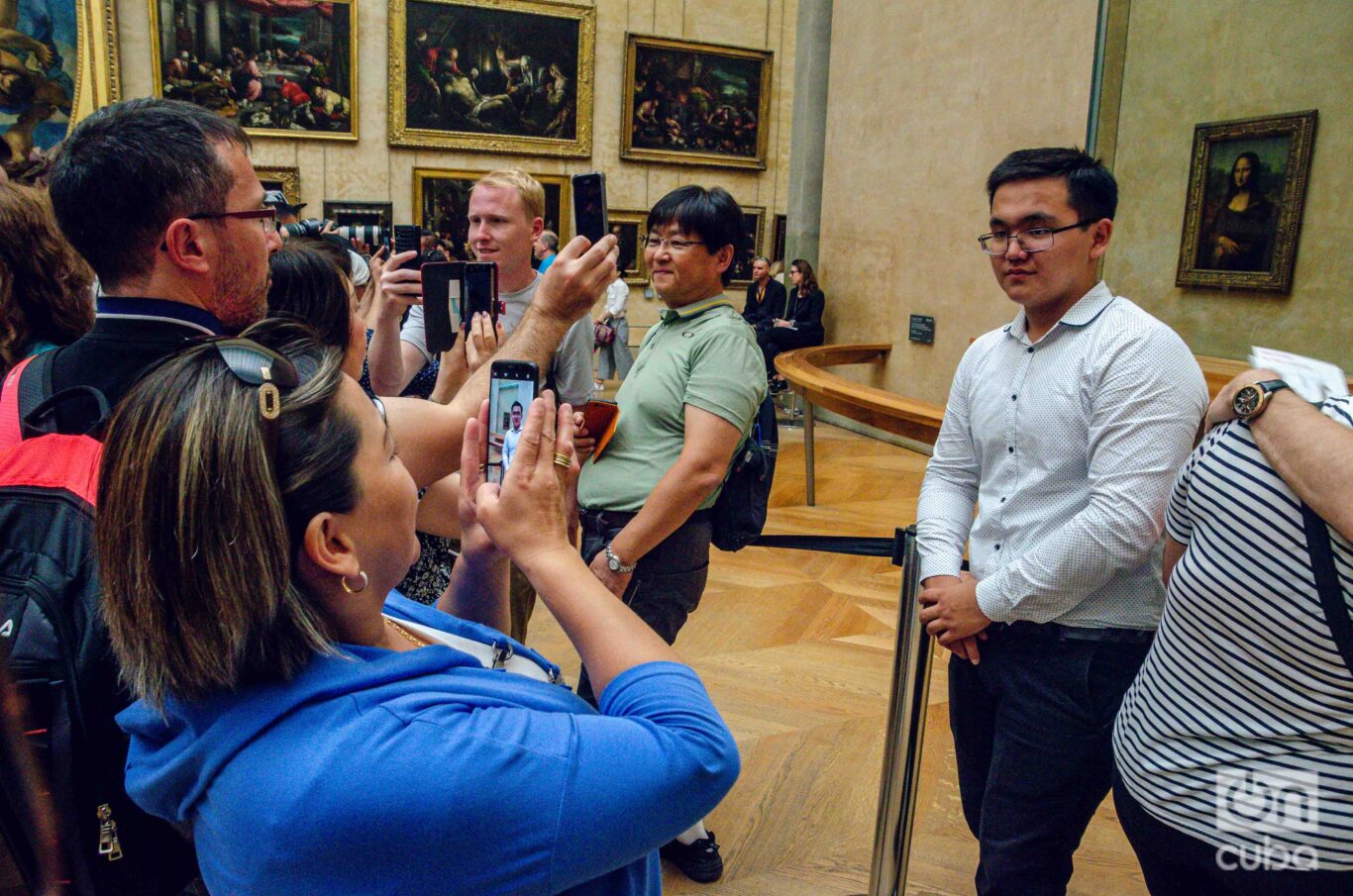

And in front of the Mona Lisa… well, I think, from a distance, I saw her scared. Surrounded by a crowd of tourists who looked at her less than at their own reflections on the screen, the lady of the Louvre seemed to implore something like: “look at me, not at your cell phones.”

It might sound nostalgic, as if everything in the past was better. But this fever of images speaks of a deeper cultural change: it is not enough to see, you have to demonstrate that you saw it. The museum, which was once a space of contemplation and silence, has been transformed into a scene of instant consumption, where the eye is mediated by the screen and the experience is worth as much as the number of “likes” it garners.

The question is inevitable: what does it mean to look? Do we really look when we focus with the cell phone? Or do we delegate the experience to an image that we will probably never review again? Perhaps in that crowd eager to pose, a void is hidden: the need to appropriate something ungraspable, to domesticate the incomprehensible of beauty in a JPG file and proclaim before the republic of social networks: “I was there.”

The paradox is that, in this new cult, one ends up with the ambiguous sensation of having been and not having been. The masterpieces, for their part, seem to be relegated to the background, eclipsed by the tide of screens around them.

Sometimes I think that the solution would be simple: ban cell phones in museums, like eating or smoking is prohibited. May the rooms once again be temples of silence, where the only click is that of thought. Maybe then we will recover what, deep down, should be the essence of a place like this: stopping to look.

Although, of course, that proposal would be considered retrograde. And it is likely that, if applied, the hallways would be empty. Because, let’s face it, for many the work matters less than the record of having been in front of it. And if there is no photo to confirm it, did the visit really exist?

Dalí, I suppose, would die of laughter at that idea. And maybe he’s right: we live in a world where clocks melt, where time runs too fast to waste it looking at a painting. Better to press the shutter, upload the photo and keep walking. Eternity, in short, is no longer measured in centuries of contemplation, but in seconds of stories.